You’ve fought and hustled your way through film school. You’ll gladly show your diploma from USC or NYU to anyone who asks—you’ll show it to them even if they don’t ask, in fact.

The films of Francois Truffaut speak to you on a personal level; Jean-Luc Godard’s use of pastiche-style narrative brings an envious gleam to your eye; you wrote a pretentious thesis on Robert Bresson’s use of negative space in “Pickpocket.”

You’ve watched “Touch of Evil” and “Mr. Arkadin” enough times to convince yourself that, “Yeah, I can do that, too. I’ll get myself a crane-cam and beat Welles at his own game.” You’re ready to take on the greats. You’re ready to subject the world to a new bit of cinematic nirvana. You are a budding cinematic genius.

Better put the breaks on your burgeoning, seething creativity for a second, though, and consider. Sure, Alfred Hitchcock used montage technique to create nearly flawless, dialogue-free sequences in his films, but he was also meticulous and exacting, almost to a fault. Just ask his leading ladies what it was like to work with him.

Francis Ford Coppola created a magnum opus to rival even his first two “Godfather” films in “Apocalypse Now,” to the detriment of his own sanity and the cardiovascular health of at least one of his actors.

Indeed, “Apocalypse Now” was such a monkey on poor Francis’s back, that actors and crew spent over 250(!) days on principal cinematography, alone. Stanley Kubrick was so insistent on perfection on the set of “Barry Lyndon,” he ended up creating special camera lenses in order shoot scenes in 18th-centry candlelight.

So you want to be a cinematic genius? You would be advised then, to take the following list of “genius-level” traits to heart. We’ll examine the DO’s and DON’TS of cinematic creativity, how they have manifested themselves in the careers of various directors and their films, in the hope they would serve as a distant early warning for anyone who would think about making the next “Citizen Kane.”

It should be mentioned that this list has been created in fun, as an amusement. It has been dreamed up as a way to honor the pound of flesh so many artists have sacrificed over the years to the gods of Hollywood. Much of the list is created as an admonishment, but, a couple of the “genius traits” could actually be taken as useful advice for anyone who wishes to make a film in the 21st century.

1. Be Assured of Your Genius

That’s right. While in the process of making your magnum opus, two questions should constantly be roiling around in your head: “Why is everybody so fucking stupid?” and “When will people acknowledge my raging genius?” This isn’t egotism or hubris, not as far you’re concerned, anyway. The quicker people realize that you’re an artist of the first order, the happier they’ll be.

You could take a nod from Fritz Lang on the set of many of his films, who insisted that cast and crew refer to him as “Herr Director” at all times.

If screamy, albeit brilliant, Germans aren’t your bag, maybe you should look at the career of a lovable scoundrel like Charlie Chaplin. Your jaw will drop when you consider the “automatic feeding machine” sequence in “Modern Times,” essentially an intricate piece of special effects with many moving parts: the camera rests on Chaplin the entire time, never panning away, which means that Chaplin either planned the sequence in detail in advance, or, he was so confident in his ability to improvise on screen, that he knew he could get the sequence in one take.

Chaplin was supposedly a tactician in post-production, so I’m inclined to believe that he planned the shit out of that sequence. Nonetheless, I can’t imagine having to do that scene again, simply because something miniscule didn’t go right, can you?

2. Establish a Coterie

Friends are cool. Friends who help you create art are even cooler. When mapping out your masterpiece, why not avoid the bother of haggling with casting agencies and labor unions, if you can surround yourself with friends and admirers instead?

Who knows, maybe you can get them on board by hustling them with meals from the on-set caterer, hookers, and a percentage of the box-office take? They’re your friends after all, right?

The key to remember, here, is familiarity and predictability. Consider: Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and George Lucas have been good friends for over 40 years, orbiting and working off of each other continually.

Scorsese leant Spielberg the services of Leonardo DiCaprio for “Catch me if you Can,” to generally good effect. Early on in Lucas’s career, Coppola, knowing full well that Lucas couldn’t write dialogue to save his life, completely re-wrote the script to “American Graffiti.” Thus, a classic was born.

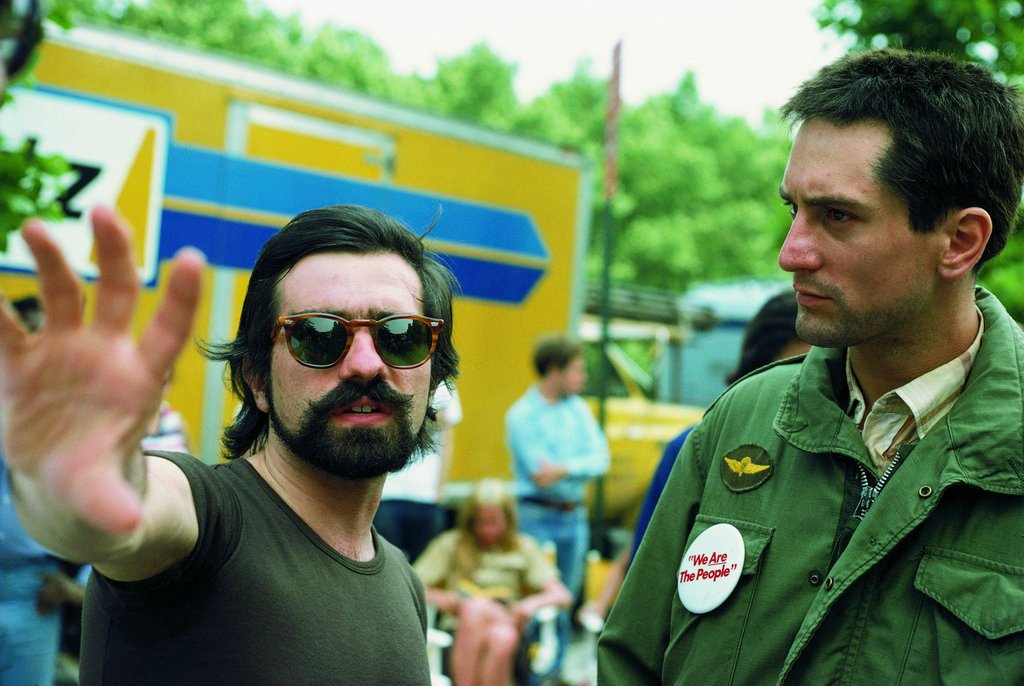

Martin Scorsese created a mean little coterie of his own with the help of Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, Harvey Keitel, and Leonardo DiCaprio, cranking out 8 films with DeNiro, 3 with Pesci, 4 with Keitel, and 5 films and counting with Dicaprio. Impressive.

Robert Altman was known to create an atmosphere conducive to collaboration and congeniality; several of his actors flourished in such an atmosphere—Lily Tomlin and Shelley Duvall among them, not to mention Michael Murphy—all of whom appeared in several of Altman’s best films.

Johnny Depp has spoken of Tim Burton’s “visionary” talent; that’s probably why he has signed on to 8 of Burton’s productions, often acting as Burton’s muse and creative canvas.

So get to work. Pester your friends and hover over them constantly until they’re crushed under the weight of your genius, or, until they’ve leant you enough money, whichever comes first—watch out, though, financial support can lead to unwanted and erroneous production credits. Look at it this way, when you’re over-budget and behind schedule, at least you’ll know who it is you’re yelling at.

3. Do the Impossible

Like Wile E. Coyote, you’re a card-carrying genius. In fact, you’re a Super Genius! Being a genius is hard, especially when you consider the decades of cinematic achievement hanging over your head like the proverbial anvil. So what’s a coyote—I mean, a director—to do? Simple: Do the Impossible. Hollywood is a dream factory, the magic store, where wishes come true, right? What’s to stop you from doing crazy shit, then?

You could build an aquarium the size of a studio lot and fill it with millions of gallons of water, just like James Cameron did when he shot “Titanic.” A bold notion, certainly, and one that shouldn’t be attempted unless you have several million dollars lying around.

Should shepherding blockbuster epics not be to your taste, you could maybe flex your art-house muscle by conceiving of your film as one continuous tracking shot that moves in and out of several spaces on the same set. Shenanigans, you will say. Hardly.

Russian director Alexander Sokurov achieved the very thing in 2002, when he shot “Russian Ark,” a seamless, visually stunning, tour of Russian history, using the Hermitage museum as a backdrop.

Sokurov had to sign off on various waivers and disclaimers from the Poliburo before he could even attempt such a thing—and even then, he was granted a mere 24 hours to shoot his film. Barkeep, set me up with a vodka tonic, with a kicker of gut-wrenching pressure, please.

If satisfying creepy government functionaries isn’t enough for you, you could venture into the furthest reaches of artistic impossibility (or insanity, sometimes there is little difference between the two) and do what German director Werner Herzog did in “Fitzcaraldo.”

Somehow, some way, Herzog thought it would be a good idea to make a movie about a character who wants to drag a steamship weighing several tons through a jungle and up a fucking mountain in order to perform an opera. Sound absurd? It is. Even more absurd—and certainly life threatening—is the fact that Herzog and his compatriots re-defined the idea of method acting by actually doing the thing itself—that is, dragging a full-sized steamship through the jungle and up a fucking mountainside!

Who would be crazy enough to sign on for this death trip? Klaus Kinski, that’s who. Kinski, who plays the obsessive opera lover in the film, became so unhinged on set, Herzog had to pull a gun on him in order to persuade him to keep doing his scenes. Strangely enough, shit got accomplished, and “Fizcaraldo” stands as a singular achievement in the history of cinema because of it.

Doing the Impossible in cinema is only for the bold and the strong at heart. Achieve the impossible, and you could be the king of the world, with several golden statues to your credit. Then again, you could end up staring into the eyes of a perturbed Klaus Kinski, as he holds a gun to your head. Your choice.

4. Be Unfathomable

When “Ulysses” was published in 1922, James Joyce reportedly said of his book, “I have just written something that will keep the critics busy for 300 years.” And he was right. Joyce had the luxury of throwing weighty statements such as this one around, because the material he produced could back it up; after all, he was fluent in 7 different languages.

One risks a literary analogy here as a way of explaining unfathomability as it relates cinema, with Joyce’s “Ulysses” as a case in point. “Ulysses” is not an unfathomable book—it is difficult, to say the least, but reveals itself as any other work of art, if one has the time and inclination to study it. Nonetheless, certain directors within the history of cinema have taken on the idea of being unfathomable as a badge of honor.

Take David Lynch, for example. A filmmaker of the first order, certainly (and one of my personal favorites), but the man can sometimes make your head spin. When asked by a film critic about the meaning of “Mulholland Dr.,” Lynch quipped, “It’s a mystery.” Great, David, thanks for the obtuse statement.

In Lynch’s films, visions both uncanny and lurid tend to dominate the scene, threatening to supersede any sense of normalcy or consistency. What are we to make of Lynch’s first film, “Eraserhead,” with its deteriorating urban structures, its eerie take on profane love, its near-constant sense of invasiveness and emotional turmoil?

What, in the end, is “Eraserhead” about? Who knows? And Lynch wants it that way. Any burgeoning cinematic genius should be well aware of Lynch and his cinematic output, but should be forewarned: emulating Lynch, as tempting as it is, should be avoided, as most directors lack Lynch’s inspired visual command of the dream-life.

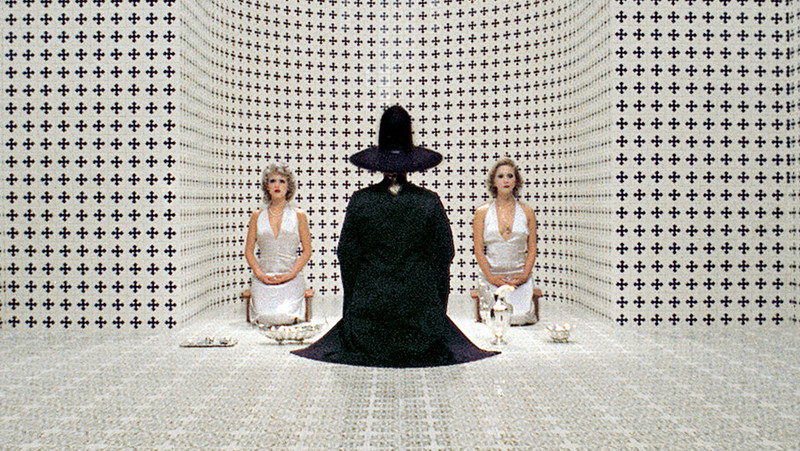

Chilean master of the avant-garde, Alejandro Jodorowsky, certainly knew how to keep the critics baffled. With films such as “El Topo,” “The Holy Mountain,” and “Santa Sangre,” Jodorowsky created a unique vision of the inner life. His films are an amalgam of spaghetti western, vision quest, and political parable, siphoned through the mind of a director who gleefully spoke of his indulgence in psychedelic drugs.

If Jodorwosky’s films are “about” anything (one could argue that they are plotless), they are maybe about humanity’s attempt to transcend itself, to connect with forces beyond itself: God, nature, the universe itself. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s all just one big party, with lots of nudity and animal sacrifices.

Any way you look at it, it’s a head trip. It should be noted that “El Topo” and “Eraserhead” were amongst the most popular films to run on the midnight-movie circuit so popular from the mid-70’s to the early 80’s, with many night owls taking in either film in an altered state of mind.

So being unfathomable, even more than wishing for the impossible, or paling around with your friends, can be incredibly risky. At best, your film could become a cult hit, like “El Topo” or “Eraserhead,” giving generations of pretentious artist types fodder to ponder over as they place their order at the local Denny’s at 2:00 in the morning.

At worst, the critics won’t know what to do with you, you’ll be dismissed as incomprehensible, and have to go back to the drawing board.

5. Direct Your Actors

Actors are simple creatures; cater to their ego—or, more often than not, their morass of insecurities—and you can get them to do whatever you want.

Occasionally, you’ll run across an actor who drops nuggets of pseudo-wisdom to an interviewer about their “obligation” to “truth,” or, how they learned so much about themselves as they rehearsed a certain role. Don’t buy into it! Take that actor by the scruff of his or her neck, point them in the right direction, put a camera in front of their face, and tell them to get to work creating your masterpiece.

Because actors are so fragile and malleable, various paths can be taken to get what you want out of them. Francis Ford Coppola allowed Lee Strasburg, the renowned acting teacher of several of his actors for the “Godfather” films (not the least of which was Al Pacino) on to the set of these films so that they would feel more comfortable.

The actors on the set of “Godfather, Part II” must have felt supremely confident about their work on the film, because Michael Corleone eventually assassinates the aging mob boss Strasburg plays in the second film.

Indeed, Coppola was extending Strasburg’s students quite a boon in allowing him on set, as principal shooting and general rehearsal is almost always a closed affair—that is, no boyfriends, girlfriends, maids, or acting teachers are allowed. being almost always considered a distraction.

In ideal circumstances, your actors won’t need to be coddled or shepherded along at all, in which case, a true sense of collaboration occurs. Such a degree of collaboration actually occurred on the set of Robert Altman’s “McCabe & Mrs. Miller.”

Altman invited his cast to the set weeks prior to shooting, encouraging them to immerse themselves within the culture of the old west gambling town in which the film takes place. By the time shooting commenced, the men had grown Civil War-beards, no one had bathed in weeks, and many of actors were downing shots of rot-gut whiskey like it was water.

Sure, the atmosphere must have been smelly and intense, but by insisting that his actors indulge themselves in taking on their roles, Altman ended up producing one of the best films of the 70’s, if not of all time.