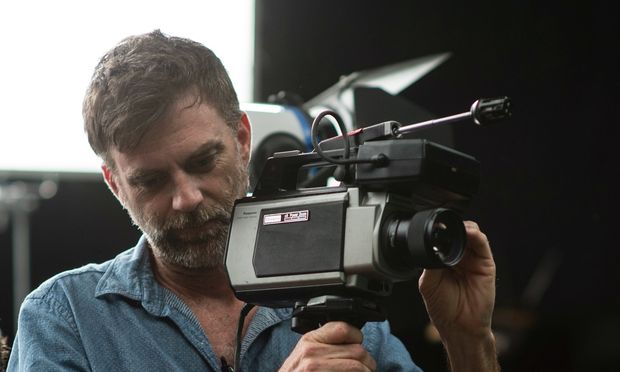

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Paul Thomas Anderson is one of the finest directors working today. From his early shorts to Hard Eight, all the way to his latest film Junun, there is much we can learn from Anderson’s work: the way he chooses his actors, wields the camera in innovative ways, his love of the long take and his ongoing collaboration with Jonny Greenwood are all elements of Anderson’s filmmaking which go towards creating such rich and valuable cinema.

Anderson famously dropped out of film school to pursue filmmaking on his own terms, so, to save the time ourselves, there is much which can be learned from Anderson’s style and technique and how it is deployed.

10. Voice-over narration is not out dated

When he was writing the screen-play for Inherent Vice, Anderson lifted much of the dialogue straight from Thomas Pynchon’s novel. Now Pynchon is not known for his clarity. Realising this, Anderson promoted the figure of Sortiliege, played by Joanna Newsom, to a more central, voice over narration role. This plays a significant role in threading the narrative of Inherent Vice together.

What Anderson proved in doing this was that voice over narration is not an out dated stylistic move reserved, primarily, for film noir as some critics have suggested. Instead, he shows that it very much has a place in today’s cinema, and can be used to great effect to engage the audience.

9. The power of the long-take

The long take is favoured by those filmmakers who wish to create a more realistic feel to and to avoid intrusive editing. Filmmakers such as Orson Welles and Alejandro Gonzales Innaritu recognised the power of the long take for submerging the audience in the diegesis of the film. Anderson is no exception to this; it has long been a favourite technique of his, a way of showing off, yes, but also of actively helping to tell the story.

For example, the lavish opening sequence of Boogie Nights employs the long take as Anderson’s way of announcing himself to the film world. After the hell he supposedly went through in making Hard Eight, he was keen to have more control over this film, and the fluid, dynamic camera movements of Boogie Nights’ opening demonstrate a virtuoso display of planning and skill with the camera.

On the other hand, There Will Be Blood uses the long take in a less obvious way to help tell the story. As David Bordwell tells us in Film Art: An Introduction, when Paul Sunday visits Daniel Plainview and Fletcher Hamilton to discuss the oil which lies under his land, Anderson uses a static long take; as each character speaks, our eyes are drawn to them, evoking a hierarchy, a subtle power fight between Plainview and Sunday, without even having to move the camera. What Anderson is continually showing us is the power of the long take to engage the audience, creating beautiful films along the way.

8. Mistakes can be a good thing.

There is a great moment in Punch-Drunk Love when the out of luck Barry decides to make his fatal call to a phone sex line. As Barry tells the worker on the end of the line his bank details for the chat he will soon receive, the camera places Barry in the left of the frame. Subsequently, the camera then pans in the opposite direction, to place Barry in the right of the frame.

In an interview after the release of the film, Anderson described how this movement was actually a mistake, that the camera had been knocked during filming. He decided to keep it in, however, for it added a nice little visual quirk. Moreover, there is another moment in the film where Barry says the word ‘food’ when he actually means ‘good’. This was a typo Anderson made when writing the film, but he chose to leave it in for the way it embellished Barry’s anxious personality.

7. Let the viewer do the work

With the release of The Master and Inherent Vice, there was a general consensus of confusion, mainly from those not so faithful to Anderson. The qualms with these two films in particular was that they were simply too confusing, too disparate narratively and stylistically to engage with. This, however, is simply a failure to engage with the films properly.

The Master, for example, is riddled with disorienting jump cuts and ambiguous sequences which may or may not be Freddie’s dreams or fantasies. What is more, Inherent Vice tells the story of Doc Sportello who is perpetually stoned. The film’s fragmented nature, twisting and turning narrative structure and hazy aesthetic allow us to feel Doc’s stoned confusion; they are stylistic choices made to engage the audience, not alienate.

Overall then, in The Master and Inherent Vice, Anderson lets the viewer do the work, allowing us to make our own associations and follow our own conclusions over the narrative for, contrary to the complaints made by many critics, a more engaging cinematic experience.

6. Be instinctive with material

Paul Thomas Anderson was widely regarded as an auteur before he had even hit 30 years of age. He has an incredible body of work behind him for the length of time he has been working in movies. By the sheer fact that he dropped out of film school to pursue a career in filmmaking on his own terms shows how Anderson has a immense amount of intuition.

This intuition manifests itself in his proclivity for filming more than he needs, often putting material in his trailers which do not make it to the final edit. This shows that he never has the film fully formed in his mind, but is open to letting the story and, at times, the dialogue unfold in a natural way.

For example, The Master is often criticised as being far too nebulous for a mainstream audience to understand. This is largely due to scenes which may or may not be dream sequences disrupting the diegesis and thus the flow of the narrative. This is, of course, an unfair criticism and is simply a failure to engage with the material. This criticism, however, is largely due to the way Anderson leaves certain material out of the film. For example, in the trailer we see Freddie turning, in slow motion, with a gun.

Now for an Anderson fanatic, this incites intrigue; why a gun? Is Freddie just playing? Does he have the capacity to shoot Dodd? The sheer fact that Anderson leaves this out of the film shows that there are many avenues his films can take when being shot. What is also shows is that, contrary to the advice given by Alfred Hitchcock, the film does not have to be fully worked out before you begin shooting. Rather, it often pays to be instinctual with material for the creation of a more realistic and human film.