It’s no news that cinema can be a powerful bearer of philosophical ideas. The Matrix has shown us that the world as we know it may not exist, Blade Runner posed questions about artificial intelligence and My Diner with Andre takes us through the whole of western philosophy. Discussing film and philosophy is great, but it’s a pity that most of these discussions end up with the same pictures, while in fact far more films are of philosophical value.

This list contains ten movies, which are way more philosophical than you might have realized before. Differing from torture-horror to comedy and time spanning more than 70 years, the films are listed in a random order.

1. The Dark Knight (2008)

It’s not that hard to recognize that Nolan’s Batman trilogy leans on some heavier themes than your average superhero movie. Batman Begins, for instance, is heavily centered on the concept of fear. In order to manipulate fear in others, Bruce first has to master his own. Because of his initial fear of bats, he chooses to conquer this fear and that’s why he becomes the Batman. In the same light, The Dark Knight deals with order versus chaos and The Dark Knight Rises with social inequality.

Fortunately, this doesn’t give a pseudo-intellectual vibe to the trilogy. Despite their ‘seriousness’, Nolan’s Batman movies remain very approachable, and very likable, as the moral themes and questions are never too explicit. There is, however, one direct adaptation of a philosophical issue to be found in The Dark Knight: the prisoner dilemma.

Imagine two people get arrested for a minor crime. The police also suspect them of a far bigger crime, let’s say a murder, but lack evidence. The two people are interrogated individually and they have no way communicating with each other. If they both don’t admit to the murder, they’ll only get a fine.

If only one of them admits he gets to be a free man, but the other one will get ten years of jail time. If they both admit, they get five year of jail time each. Just imagine yourself in their position and you’ll see there’s no easy decision to be made. Philosophers argue that this dilemma (originally deriving from game-theory) has something to say about the nature of our morality.

The Dark Knight has a slightly different take on the theory, although the essence remains pretty much the same. In order to create chaos and mayhem in Gotham, The Joker rigs two ferries with explosives, one ferry transporting civilians and the other transporting prisoners. He then promises to blow each of the ferries by midnight or if someone tries to escape, but will let one live if it blows up the other.

I won’t spoil the outcome of Joker’s social experiment, in case you didn’t see the movie yet. The reason why it’s philosophically interesting, though, is that The Dark Knight’s ‘prisoners dilemma’ adds an extra dimension to the original one.

Because the decision of one ferry has a direct influence on the other one (getting blown to pieces), both ferries know that the other one didn’t make the call yet. This element of empathy makes the decision even harder, and as philosophy in movies at it’s most effective, it gets moviegoers to think ‘what would I do?’.

2. Clerks (1994)

Clerks, a 1994 dark comedy directed by Kevin Smith, presents a tough day in the life of a store clerk called Dante. First of all, he has to work on his day off and secondly; he finds out that his ex-girlfriend (whom he still loves) is getting married. The film owes it’s cult-status to it’s a mixture of weird-ass characters, hilarious situations and sharp dialogue. This dialogue frequently features existentialist beliefs.

Out of all philosophical doctrines, existentialism is the one most represented in cinema. This might be because it’s meaning isn’t too hard to grasp for the audience: if God doesn’t exist, man doesn’t have an essence that precedes his existence. Therefore, it’s up to each individual to decide how to live. Our lives aren’t any longer determined by anything except ourselves (like religion), and that’s why we have to take full responsibility for every choice we make.

In Clerks, Dante embodies the opposite of this existentialist ideal. Throughout all the shitty stuff that happens to him, he repeats that he “isn’t even supposed to be in the store today.” His coworker Randal replies to him with an unambiguous “Fuck you”. He accuses Dante of passing the buck instead of taking responsibility.

Dante could have stayed at home if he wanted, but he made the decision to go to work. As a true existentialist, Randal reminds Dante that he himself is the only person to blame for the situation he is in. Like a modern Sartre, he encourages us not to behave like ‘fucking cowards’, but to make changes in life if we want to improve it.

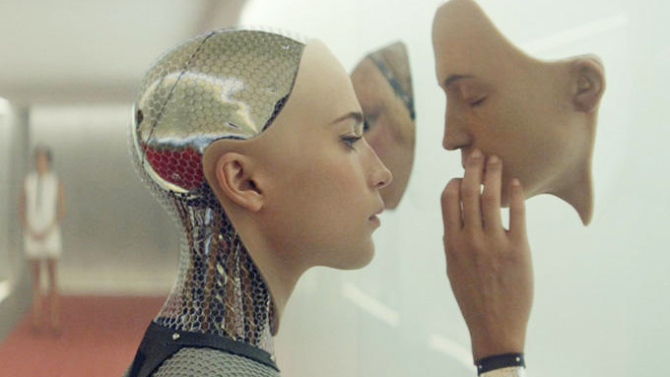

3. Ex Machina (2015)

As most movies concerning artificial intelligence, Ex Machina puts forward some exiting questions about the ever-shrinking gap between man and machine. The story involves Caleb, a young programmer who is selected to participate in a groundbreaking experiment by evaluating the human qualities of a breathtaking female A.I., who goes by the name of Ava. During their conversations, Caleb starts to develop certain feelings for Ava, while she tries to manipulate him in order to help her escape from the laboratory.

Funnily enough, for philosophers of mind, Ex Machina’s take on artificial intelligence isn’t interesting at all. The way Ava thinks and behaves is way too oversimplified, compared to current A.I. studies. Furthermore, most of the philosophical references explicitly made in the movie are quite poorly used (Wittgenstein’s Blue Booklet) or even incorrect (the thought experiment of Mary in the black and white room).

The reason that Ex Machina is so interesting for philosophers, however, is that the plot itself makes a very bold philosophical statement. A question often asked by philosophers of mind is ‘when do we ascribe consciousness to a person or a being?’ The obvious answer would involve a number of conditions that have to be met. However, most present-day philosophers of mind proved this method to be insufficient. The matter of consciousness simply is too complex for approach.

Ex Machina asks exactly the same question, as Caleb has to decide whether Ava is or isn’t a conscious being. He starts believing she is, from the moment that she reads his thoughts and his emotions.

This is philosophically profound, because in this manner consciousness becomes social, requiring mutual recognition, instead of it being individual, requiring certain conditions. Ex Machina is such an admirable film because this idea of consciousness as social concept is no gimmick but makes an essential component of the story.

4. Citizen Kane (1941)

Not only is Citizen Kane one of best movies ever made, it’s also a treat for philosophers. Some films put character to philosophical doctrines; others use philosophical problems to create certain situations. What Citizen Kane does, is the opposite. It doesn’t teach us how to live a good and philosophical life but it shows us how exactly not to.

The film presents the story of the fictional newspaper publisher Charles Foster Kane. After his death, a journalist tries to find out the meaning of his last utterance: ‘rosebud’. Through interviews with Kane’s closest ones, the journalist starts unraveling what kind of man Kane really was.

Kane never really valued telling the truth through his newspapers, and his political pretenses were hollow. The only thing he really seemed to want was to gain money and power, as a replacement for the love he never got during his childhood. Kane died a very wealthy, but mostly a very lonely man.

Kane defined happiness and success in all those terms that Socrates, ancients of ancient philosophers, once judged to be of little value: possessions, consumption, and social position.

According to Socrates, to live a good life means to question all things you hold to be true and to be critical, especially at yourself. Hence his most famous quote: “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Kane’s goals and motives remained unexamined, which destined his life to be out of control, and condemned the public figure he produced to be hollow.

From this point of view, Citizen Kane might be more of an a-philosophical movie, rather than a philosophical one. It does make Socrates and philosophy relevant, though, and that’s always a good thing.

5. The Fault in Our Stars (2014)

It takes some fantasy to see the philosophical implication of The Fault in Our Stars, a young-adult box-office hit film about two teenage cancer patients on a journey to visit a writer in Amsterdam. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t any. Near the ending of the film Hazel and Gus finally meet their writer, who in fact turns out to be a giant shitbag.

As he’s pointing them out the harsh realities of life, he starts about a philosophical thought experiment called the ‘trolley problem’. Hazel interrupts him, however, saying she doesn’t want to hear about it. Unfortunately, that’s as far as literal philosophy goes in The Fault in Our Stars.

It’s a pity that the trolley problem remains unexplained, since it has to do with the film’s plot. The thought experiment involves a train rushing towards five people who are tied onto the tracks. On a secondary track, only one person is tied up. You stand by a lever, which changes the track. If you pull it, one person dies. If you do nothing, five people die. What is the correct action to take?

The many variations of this thought experiment are great to bring up at boring parties, but they’re not really relevant to us. What is relevant, though, is that The Fault in Our Stars is itself a (very) loose variation on the trolley problem. In the film, Hazel knows she is going to die from cancer. She struggles with whether or not she should love anyone or allow herself to be loved while she is, in her own words, a grenade that will eventually explode.

As with the train and the lever, Hazel has to choose how many people she will hurt with her own dying. This corresponds to the trolley problem at least on a spiritual level, and may even bring teenagers to philosophize between tears.