6. Jurassic Park (1993)

Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, about a theme park full of cloned dinosaurs, isn’t exactly the first movie you’d think of to discuss with your film- and philosophy loving friends (assuming you have these). However, as Spielberg himself pointed out multiple times, there’s a big moral question to the story. DNA cloning may be viable, but is it acceptable?

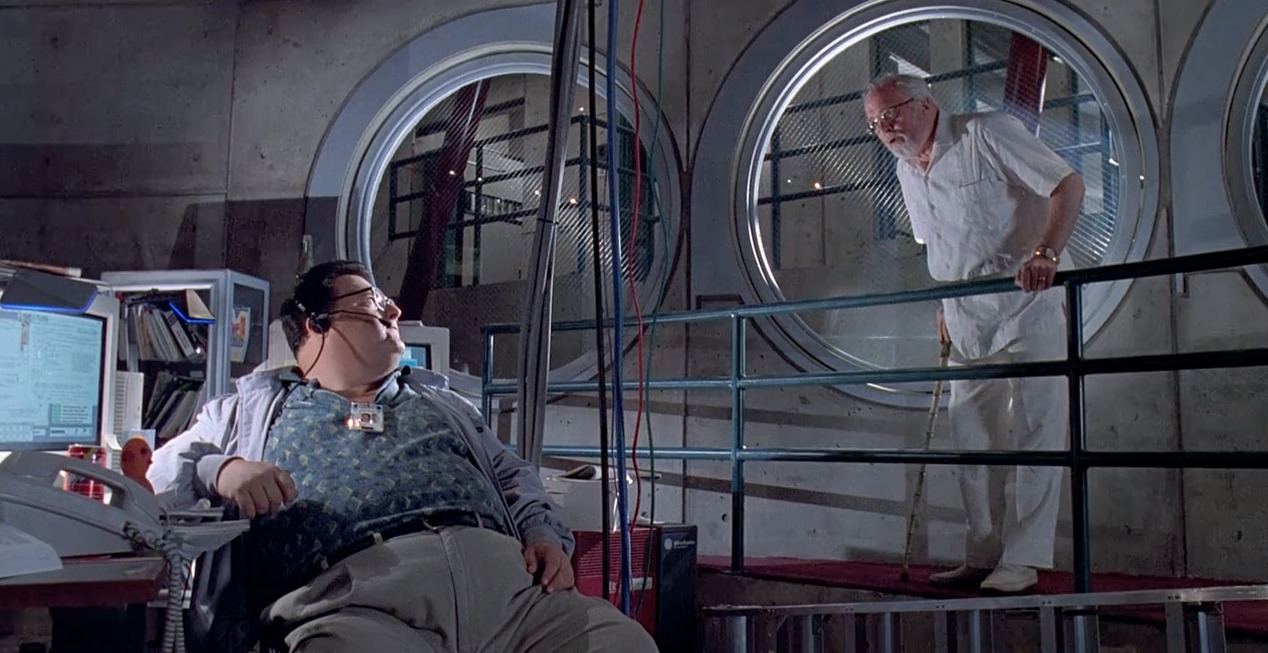

A problem that rises up has to do with something psychologists and philosophers tend to call the ‘God complex’. The term refers to individuals or groups who literally think they’re God and, because of that, that they can decide over life and death. In Jurassic Park the character of Dr. Ian Malcolm beautifully criticizes this aspect of modern man.

After hearing what’s been accomplished he notices: ‘God creates dinosaurs. God destroys dinosaurs. God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs’, also sharply referring to Nietzsche’s death of God. Throughout the movie Malcolm keeps his skeptical attitude toward the cloning of dinosaurs, thereby reminding viewers that technological advancement isn’t always ethically grounded.

For a Hollywood blockbuster, the film is actually pretty unique in doing so. In Godzilla or The Incredible no one asks ‘I know we can do this, but should we?’. Some philosophers argue that our contemporary society is determined by technological development instead of social or ethical beliefs and ideals.

Especially in such an age it’s important for art to give rise to questions concerning this development and have its spectators do so too. Jurassic Park unexpectedly does a remarkable job at doing this, even spawning three sequels showing us how technological advancements can harm society.

7. In Time (2013)

In Time is a pretty bad movie, and that’s okay. Bad movies can still feature some cool ideas, and that’s exactly the case with In Time. The film takes place in a not too distant future, where time has replaced money as a currency. Humans stop aging at 25 and are engineered to live only one more year, unless they buy their way out of it.

The rich earn decades at a time, becoming essentially immortal, while the rest beg, borrow or steals enough hours to make it through the day. In the midst of all this is factory worker Will Sales, played by Justin Timberlake. The story is a little overcomplicated, but it boils down to Sales trying to bring down the system and giving more time to the poor, while trying to get off with Amanda Seyfried.

This concept can definitely wet the appetite of philosophers (concept of time as a money-replacing currency, not concept of getting off with Amanda Seyfried). Social inequality is a major theme in political philosophy and it’s surprising how few sci-fi films deal with this on a serious level.

In Time at least tries to tell a modern Robin Hood tale, and although most of the film doesn’t really work, it’s notable how convincingly the day-by-day lifestyle of the poor is brought to attention. The film criticizes the ever-growing gap between rich and poor like a futurists Marxist manifest, pleading for welfare redistribution.

Besides In Time’s critique on social inequality it also poses –not very accurately, but still– a big ethical question: how much is a human life worth? In capitalism human value is quite often reduced to economic value, but may we ever completely reduce lifetime to money? This may sound super-abstract, but it’s actually not that far from reality.

Biogenetical technology is rapidly evolving and scientists don’t exclude the idea of eternal youth. It may turn out that In Time’s predictions become reality in the near future. Maybe In Time once even gets to be reviewed as a modern fortunetelling classic, but that’s presumably less likely.

8. The Big Lebowski (1998)

The Big Lebowski didn’t land with smashing box-office numbers, but became a cultural phenomenon over the course of the years. Up until today this has led to themed parties, a rising popularity of White Russian cocktails and a pop-up nightclub that is appropriately called Club Lebowksi. The movie, directed by the Coen brothers, is basically about a guy (the Dude) aspiring to get his stolen rug back. Along the way, viewers learn everything there is to know about bowling, vaginal art and nihilism.

Nihilism is a philosophical doctrine that suggests that there are no such things as objective truths, values and morals. The term derives from the Latin word ‘nihil’, meaning ‘nothing’, and has been used in different ways. It mostly got famous for it’s use in Nietzschean philosophy. According to the nihilist view our existence (action, suffering, willing, feeling) has no meaning. Because of this, nihilists don’t need any moral principles and they can do whatever they feel like doing.

The clearest Lebowskian reference to nihilism is found in the two German thugs who steal The Dudes rug. They’re literally called ‘the nihilists’ and at a certain point threaten The Dude by saying: “We believe in nothing, Lebowski. Nothing. And tomorrow we come back and we cut off your Johnson.” Needless to say, this caricature of nihilism is quite over-the-top.

On a deeper level, however, we find that both the film’s plot and its main character are fundamentally nihilistic. As far as the story of the movie goes, nothing really happens. There seems to occur nothing of any real meaning or consequence, apart from Donny’s death, and even that doesn’t stop The Dude and Walter from competing in the semis of a bowling tournament.

As for The Dude, he just goes with the flow of the meaningless world around him and he doesn’t really care or worry about anything except for his stolen rug. As he says himself: “The dude abides.”

9. Hostel (2005)

Different from others films in this list; Hostel isn’t so much a bearer of philosophical ideas. Instead, the film has become a topic of philosophical discussion itself.

The film, presented by Quentin Tarantino, tells the story of three backpackers who end up in a Slovakian hostel. There they find themselves preyed upon by a group of sadistic, rich ‘clients’, who pay to torture. According to some, the film criticizes modern consumerism and even refers to Marxist and Nietzschean philosophy. More interesting and less far-fetched, however, is the question what Hostel (and torture-horror in general) says about the morality of its audience.

We find a penetrating analysis in Jeremy Morris’ ‘The Justification of Torture-Horror’. He believes that films like Hostel require an audience not only capable of empathy with the victims, but also able to share something of the joy of the torturers. In order to enjoy sadistic torture-horror, the audience must experience both of these conflicting sentiments. Being conflicted in that way is not the mark of immorality; on the contrary, it is a moral vindication of the audience.

In this way, movies are able to put viewer’s morals to the test. Films like Hostel are often referred to as immoral cinema, but fans of horror-torture aren’t necessarily immoral at all; they’re justifying their ethics.

10. Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

How do Star Wars and philosophy relate to each other? Well, apart from the fact that both fans of Star Wars and philosophy often share their part in geekiness, the lifestyle of the Jedi refers a lot to the ancient philosophy of Stoicism.

Stoicism is a school of philosophy founded by Zeno in the early 3th century BC. Indeed, that’s quite a time ago. Today we remember the Stoics mostly from their ethics.

We still say someone has a stoic character if he or she is rather unemotional of indifferent to pain. However, this conception of their ethics is incorrect. The Stoics did not seek to extinguish emotions; rather, they sought to transform them in order to develop clear judgment and inner calm. Logic, reflection, and concentration were the methods of such self-discipline.

Did you notice that the Jedi also seek this very same sense of clear judgment, inner calm and self-discipline? In The Empire Strikes Back, Jedi-master Yoda time and time again tells Luke to ‘control his anger’ in the same way the Stoic Seneca once famously wrote that ‘anger is without reason’.

Contrary to this anger, the virtues of the Jedi are mainly the same as the Stoics: calmness, peacefulness, patience, seriousness, deep commitment and wisdom. Given these virtues, Yoda certainly resembles what the ancient Stoics described as the sage, the ideal person who has perfected his reason and achieved complete wisdom.

The Stoic ideal might even be more urgent in Star Wars than in real life, since the Dark Side and the way of the Sith are opposed to it. If we’re not able to control our own anger, we may turn out to be just like Anakin and become as evil as Darth Vader. It’s pretty awesome that an ancient Greek philosophy takes such a vivid form in the Star Wars saga and that a generation of children unknowingly grew up with Stoic ideals.

Author Bio: Maarten van Gestel dropped out of the Film Academy in order to study philosophy in a picturesque city in The Netherlands. Besides philosophizing, he writes for the university magazine – and still tries to squeeze as much film-related stuff into his life.