“Film as dream, film as music. No art passes our conscience in the way film does, and goes directly to our feelings, deep down into the dark rooms of our souls.” –Ingmar Bergman

Filmmakers have, since the invention of the medium, been an elite crew. Often well-educated, they ensure that their films carry multiple meanings, have many allusions, and are enjoyable on several levels. This is, I think, true of even the most banal, asinine, and horrific of films and action movies.

In this list, I highlight 14 directors that are particularly thoughtful, whose works are often deeper, allusory, and philosophical in nature. I would even go as far as to call these 14 “Philosopher Kings”, but I want to be sure to welcome other suggestions that I may have overlooked or neglected due to limited space.

1. Terrence Malick

“Terry” is certainly my favorite living director, and probably my favorite director of all time, so I have to admit bias here. His films are always thoughtful, and it is because of this that he tore the film world wide open in 1973 with Badlands. He studied philosophy at Harvard and Oxford, studied under Stanley Cavell and Heidegger briefly, and taught philosophy at MIT.

As if these credentials don’t speak enough, his films speak volumes to his education because they are full of philosophical quotes. The Tree of Life and To the Wonder include lines almost directly taken from Kierkegaard, The Thin Red Line talks about Homer, and all of his films strive to create a Heideggerian “poesis.”

Moreover, if you’re looking for beautiful, meandering cinema with thoughtful dialog and voiceovers composed by a new philosopher, Malick’s films will not disappoint. The Tree of Life, an exegetical work on the book of Job, offers his own musings on life, theology, and existence, and won him the illustrious palm d’or at the Cannes film festival in 2011. I recommend starting there.

2. Andrei Tarkovsky

Similarly, Andrei is a philosopher himself, and all of his films echo this expertise. He has written works about philosophy and film (Sculpting in Time being his most famous here), and composed poetry.

A Voyage in Time is a Tarkovsky film actually documenting this life, as he tours the countryside preparing to make Nostalghia and writes poetry along the way. His background is interesting, in that his mother studied literature, his father was a nobleman and poetry translator in Ukraine, and he himself studied piano, art, and film.

A true renaissance man, his films deal with a variety of topics and span several genres, as he toys with his own thought experiments and musings on life, nature, existence, and free will. A good friend of Ingmar Bergman, he worked to emulate the work of other great philosophical directors like him, Bresson, Bunuel, and Dreyer.

Malick seems to reference Tarkovsky frequently, and I think that is because Tarkovsky served as such a great example of a poetic philosophical director working to sculpt the medium. I recommend watching The Sacrifice or Stalker to see some of his philosophy in action.

3. Ingmar Bergman

An unparalleled genius, Bergman was the son of a Lutheran minister and chaplain to the King of Sweden. He lost his faith at an early age and struggled with his existence for the rest of his life (this is most visible in his film Winter Light) and so he turned to philosophy as a means to rationalize everything.

He studied art and literature at Stockholm University, and his films focus on a variety of issues ranging from existence and mortality to faith and sex (yes, all of these are related in some sense, too). He alludes to anyone concerned with existentialism, metaphysics, or faith (and yes, I mean anyone), but perhaps most frequently and blatantly to Nietzsche and his philosophy, which Bergman rejects.

Truly though, Bergman is his own philosopher, like Tarkovsky, and his films portray a unique, sometimes absurdist take on life that can rarely be glimpsed elsewhere (Tarkovsky excepting). While he worked contemporaneously with Tarkovsky, it is his films that have influenced more filmmakers and are more well-known thanks to his artful narrative skills and cinematographic mastery. I recommend Fanny and Alexander or The Seventh Seal as a way to break into Bergman’s philosophy.

4. Carl Theodor Dreyer

Born an illegitimate child in Denmark, Dreyer bounced around between orphanages until he was adopted by a not-so-loving family. A stalwart conservative, he first worked as a journalist and then became a title-card writer for silent films at age 24. At first, he had very limited success, but after some time his films grew in popularity and quality, with his first major success being The Passion of Joan of Arc. This film follows Joan’s dialectic of faith, and toys with reality as we perceive it and reality as it is.

His later films, Gertud and Ordet are no less philosophical, and are actually more intricate explorations of the same themes. Gertud deals with faith and love, as a woman ends her marriage and falls for another man. Ordet deals with faith as three children, an atheist, a moderately religious child, and a child who went insane studying Kierkegaard and now thinks that he is Jesus Christ, all deal with the trials of life.

Both are deep explorations of faith and individualism, as one individual struggles to bring his reality to fruition against the will of others. Ordet is the most comprehensive and expansive, so I’d recommend working down from it.

5. Luis Bunuel

Born into a wealthy and large Spanish family, Bunuel was a devout Catholic. He went to a strict Jesuit school where he was a top student until he decided to stop attending. He also served in Mass and took the Eucharist daily until he rejected the Church for its illogicality, power, and wealth.

At the University of Madrid, he studied agronomy, engineering, and, you guessed it, philosophy. He became close with Salvador Dali and the lesser known poet Federico Garcia Lorca, and thus became an integral part to the founding of the Surrealist movement.

All of this found its way into his films, which are full of Marxism, absurdism, existentialism, and other schools of critical thought. His best known are The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeosie, Belle De Jour, Un Chien Andalou, and Simon of the Desert, but I would recommend some of his lesser knowns too, such as Viridiana and Nazarin.

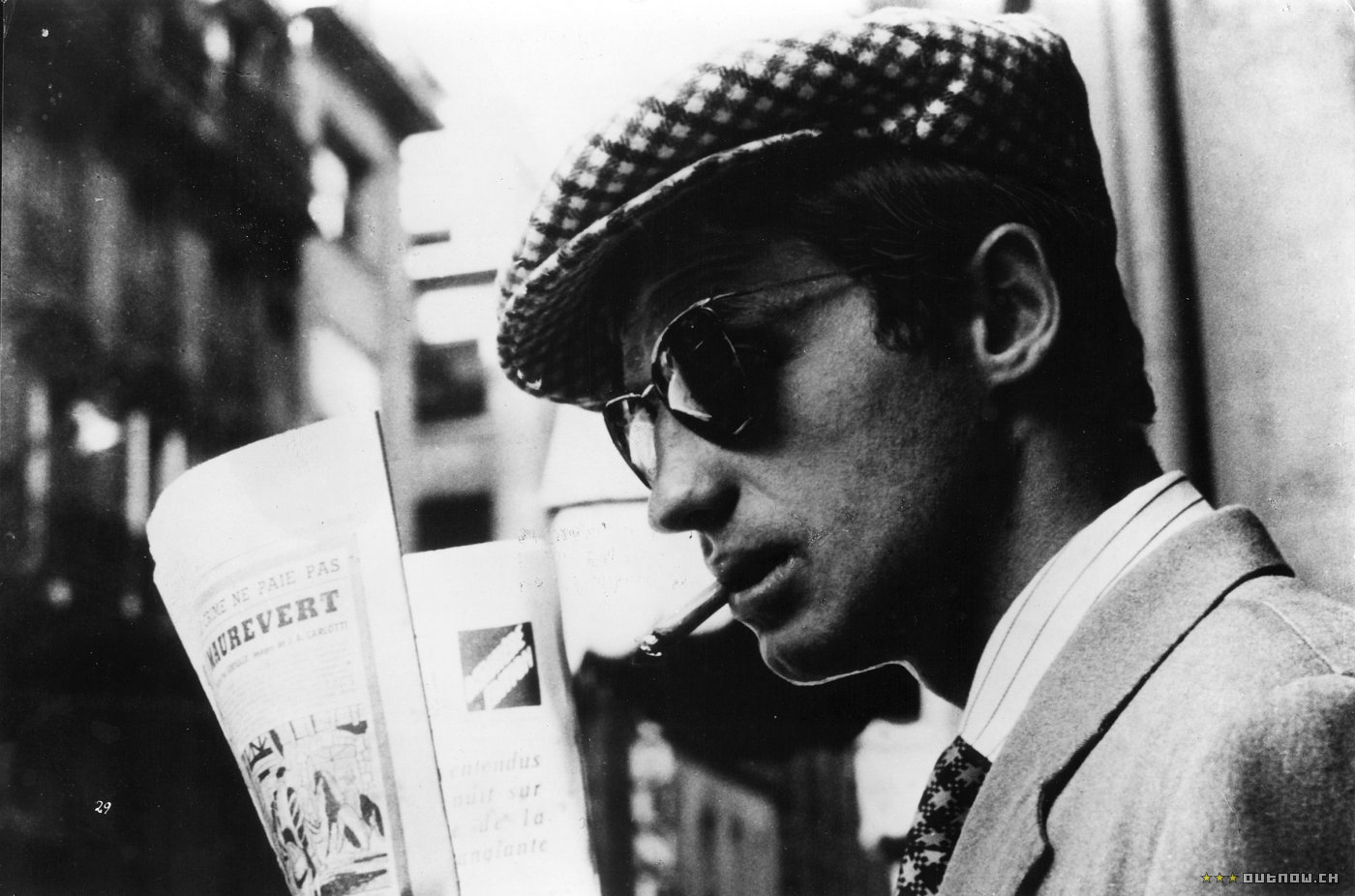

6. Jean Luc-Godard

Born to wealthy protestant parents in Paris, Godard moved to Switzerland at a young age and stayed there, for the most part, during WWII. In his youth he studied anthropology at the Sorbonne, under writer Jean Schlumberger, and with a group of film critics in the New Wave movement, but all only half-heartedly (in fact, it seems he didn’t even attend class at the Sorbonne).

His real route to film began with film criticism though, as the cine-clubs gained popularity in France. There he met Truffaut and many other key French film critics, and eventually he went on to make films.

Breathless, my favorite, features, as all Godard films do, dozens of pop culture references and a philosophical dilemma as one man tries to face off against government and to be truly free. Reflecting his radical right background, Godard often pushes the limits and questions authority in his films, but the answer is often a more moderate and appropriate response. I’d recommend starting with it to get a good taste of what Godard can offer.

7. Woody Allen

Born to a devout Jewish family in Brooklyn, Allen had a rough childhood as he saw his parents fight and had a bad relationship with his mother. He attended Hebrew school and New York University until he dropped out after failing a film class, and briefly attended the City College of New York. He then served as a comedy writer and comedian for the next 20 or so years until his first film, What’s New Pussycat in 1965.

Since then, he has made a film a year, with his most famous being Annie Hall and Manhattan. Not philosophical on the surface, Allen’s films are full of his dry, critical humor which allows him to toss out pithy comments on life, mortality, faith, reality, and everything in between. All of his films are worth the watch, but I particularly recommend these most famous two to those that haven’t seen them.