5. Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (Christopher McQuarrie, 2015)

After shooting the insane, Pixar-style, anything-goes-style action in Brad Bird’s propulsive Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, it might have been realistic to ask what else Elswit might have thought he needed to do within this realm of big-budget pop-corn filmmaking. And after this latest installment, I think it’s safe to say that he should be a required crew member for all future series efforts.

The MVP of Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation, which was directed by Christopher McQuarrie, is clearly Elswit and his ace camera team. I can’t get over some of the shots in this latest foray in the franchise; literally every single image is pristine and gorgeous. His overwhelming sense of what is photogenic continues to dazzle the eyes and set the screen ablaze and his stunning photography and sharp camera placement in this film is extraordinary to observe and study.

The stunts and action sequences pop with authority — the car and motorcycle chase in Casablanca is utterly superb — and it’s clear from watching that Elswit knows no bounds as a cameraman. The rest of the film is serviceable and fine — it’s predictable, it’s exposition heavy, Tom Cruise is doing solid Tom Cruise here, nothing remotely challenging except of course in the physical sense.

Simon Pegg and Jeremy Renner get some good laughs, and repeatedly, the film’s thunder is stolen by the sexy and confident Swedish actress Rebecca Ferguson, who kicks a ton of cinematic butt without taking names, and looks extremely sexy in evening gown and bathing-suit attire — she’s like a more athletic version of Ruth Wilson. But it’s Elswit and the rest of the ace tech crew including second unit director Gregg Smrz and stunt coordinator Wade Eastwood who were clearly working overtime to present some big-screen thrills that we’ve not yet seen before.

Elswit and McQuarrie were wise to hold on that now-famous master shot of Cruise dangling off the side of that AC-30 cargo plane — they knew what they had in that moment. And that motorcycle/car chase sequence was absolutely breathtaking, with Elswit presenting clear spatial geography while showcasing some extremely dynamic angles and perspectives during the middle of the increasingly dangerous and visceral beats of action.

If CGI was used, it was flawless, and that’s another aspect to Elswit’s work that enhances everything – it always looks real, no matter the genre or shooting style.

4. Syriana (Stephen Gaghan, 2005)

Gaghan’s reliably smart writing and surprisingly ruthless direction set the stage for this no-nonsense geopolitical thriller, with George Clooney giving a terrific, Oscar winning performance as a downbeat CIA operative caught in the middle of modern day terrorism. Elswit shot the film in rugged, rough and tumble fashion, utilizing natural color saturation, hand-held cameras, and a live-wire sense of unpredictability which helped to increase the tension from scene to scene.

The entire cast is magnificent from top to bottom, with the likes of Matt Damon, Amanda Peet, Jeffrey Wright, Chris Cooper, Tim Blake Nelson, William Hurt, Mark Strong, Christopher Plummer, and the terrific Alexander Siddig all giving strong performances. The film also makes pointed jabs at America’s over reliance on foreign oil and the sketchy inner workings of that entire trade and industry, while also shining a spotlight on the more topical than ever subject of religious radicalization.

Elswit shot the action in an unfussy manner, never going for anything over the top or too slick, making the most out of the impressive physical locations, and relying more on smart camera moves and placement than show-off moments of look-at-me-style.

When combined with another strong Alexandre Desplat’s score that’s both riveting and contemplative at the same time, the film carried a sense of weight and importance without ever feeling pretentious, with Elswit’s frequently arresting imagery keeping he film grounded in reality. It’s taken a long time for Gaghan to select a directorial follow-up to this great piece of work, but it looks like in 2016 he’ll be reteaming with Elswit on a jungle-set thriller which has all sorts of potential.

3. Punch Drunk Love (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2002)

Punch Drunk Love is so many things all at once: A heartbreaking ode to Los Angeles loneliness, a troubling study of unchecked mental illness, a sweet and unlikely romance born out of our innate human nature to be accepted and loved, and a transcendent stylistic experiment masquerading as a “romantic comedy.”

Anderson’s brilliant, hypnotic, and completely consuming film is a deeply idiosyncratic work that owes a ton of its singular success to the radiant work of Elswit. His lens-flare-inflected widescreen cinematography is nothing short of astonishing, with sinuous stedicam work, jagged moments of hand-held photography, and startling camera placement used in an effort to keep the audience guessing.

For 90 minutes, you’re inside the rocky headspace of Adam Sandler’s Barry Egan, a private loner working a non-descript job in a non-descript warehouse in the classically non-descript San Fernando Valley, and it’s as jolting to him as it is to us when he meets the love of his life, in the form of Emily Watson, as random of a romantic partner for Sandler that could ever have been discussed or cast.

Philip Seymour Hoffman brings menacing edge as the film’s antagonist, but the fact that the villain of the piece was constructed more as a psychological tool of frustration than anything else only adds to the increasing headiness that the film’s mood evokes; similar to works like I Heart Huckabees, Birdman, Queen of Earth, and other stories that explore the psyches of troubled protagonists, Punch Drunk Love has a ton to say about its intensely adult themes, while the restless aesthetic quality ups the anxiety level at almost every turn.

Elswit’s dreamy work on this film ran a direct opposite to the near constant percussive musical score from Jon Brion, which amps the tension levels all throughout. Elswit shot the romantic interludes in close-up, filling the 2.35:1 frame with the highly emotive faces of his two leading actors, with the entire film serving as a reminder that when paired with quality filmmakers and incredibly talented craftspeople, Sandler is capable of being more than a juvenile cinematic joker.

2. Boogie Nights (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1997)

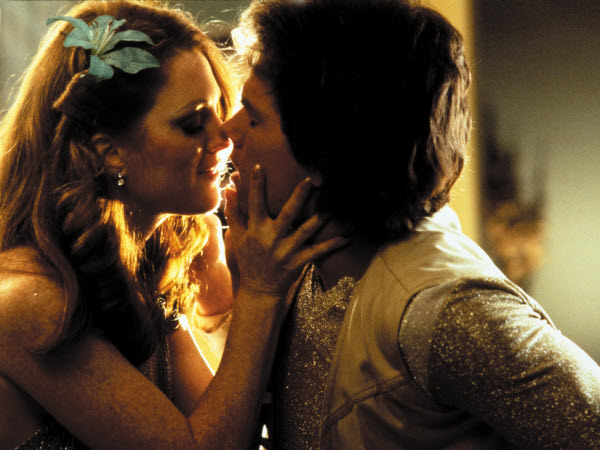

A dynamic sense of cinema fills every single frame of Anderson’s tour de force Boogie Nights, with Elswit’s slick and Scorsese-esque imagery creating a kaleidoscope quality of 70’s glitz and glamour followed by 80’s despair and depression.

The film is hysterical, obscenely well written, passionately acted, and directed with a sense of overall showmanship that feels indebted to early Scorsese and De Palma. And, most importantly, it’s stunningly photographed, with the film giving off a visual buzzing sensation while viewing. Elswit busted out all of the ticks in this film – split screens, fast zooms, whip-pans, dazzling stedicam work, gritty moments of hand-held authenticity, and some of the best uses of extreme close-ups in any movie to date.

Back in 1997, Boogie Nights felt like a total blast to the solar plexus of American cinema, and over the years, it’s inspired any number of filmmakers and storytellers, just as PTA was inspired by so many who had come before him. From one scene to the next, the viewer is treated to a dizzying array of people, places, and things, with Elswit’s gliding and expressive camerawork capturing the Altman-esque cinematic tapestry with style and clarity.

There are so many scenes that work brilliantly precisely because of the decisions that Elswit seemingly made as director of photography, from decisions on where to place certain actors within the frame, to how much stedicam would be mixed in with traditional dolly-work and stationary set-ups. Boogie Nights can’t help but feel like a grab-bag of sorts from a visual standpoint, the type of film that feels positively electrified by the notion and chance to create something magical.

One of the best scenes in the film happens to be its most emotionally tragic (Scotty J.’s romantic confession on New Year’s Eve to Dirk Diggler in front of his new car), and it’s how the scene was shot (all in one, long, unbroken, hand-held take which emphasizes the physical space between the two actors and genuinely ups the anxiety levels) that has allowed it become the classic that it has.

The scene also contains the most heartbreaking piece of acting that Philip Seymour Hoffman ever gave. Raw, vulnerable, terrified, humiliated, and finally, perfectly human, it’s a tour de force of a sequence for all of the creative talents, and a further reminder of how powerful big screen storytelling can be when all of the elements click into high-gear.

1. There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007)

There Will Be Blood is more interested in people, places, and psychological decisions than concrete plot developments and easy to define motivations, which is the sort of cerebral style that can afford a cinematographer the chance to run wild with bold, expressive imagery.

The film pivots on three or four big set-pieces, with an oil rig explosion and fire serving as one of the major highlights, and Anderson and Elswit handle the muscularity of the film with a heightened beauty that recalls magic-hour Terrence Malick on more than one occasion. During the oil-rig fire sequence, Anderson and Elswit staged a bravura tracking shot through all of the action that demands to be repeatedly studied in terms of its virtuoso technical accomplishments, not to mention its importance to the narrative.

As with any film by PTA, the camerawork is never unmotivated, and because Elswit is such a smart image maker, he’s able to combine the narrative force of PTA’s plotting with a phenomenal sense of pictorial grandiosity. Anderson had never made an old-school period film before There Will Be Blood, and long had been considered one of our most modern of filmmakers, after crafting with Elswit a variety of distinctive portraits of Los Angeles malaise such as Sydney (aka Hard Eight), Boogie Nights, Magnolia, and Punch Drunk Love.

In There Will Be Blood, Elswit, along with the help of master art director/production designer Jack Fisk (Days of Heaven, The New World), evoked an era of simple, stark beauty and dark menace, with open exteriors framed in massive widescreen scope, with little details filling the edges, Dimly lit and period-authentic interiors dominate the second half of the film, with the oppressive color palette and ornate decorations suggesting the insular suffocation of its tragic main character, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day Lewis in a legendary performance).

There’s a moment about halfway through the film that shows Plainview admiring an oil fire for an extended period of time, allowing for more contemplation than is normally afforded to characters in any given film; it’s truly a movie moment worth a thousand words, and an instance in the film where you realize what Elswit and Anderson were hoping to achieve with this one of a kind motion picture.

Author Bio: After spending close to a decade working in Hollywood for the likes of Jerry Bruckheimer, Tony and Ridley Scott, and Gary Ross, Nick Clement has taken his passion for film and transitioned into a blogger and amateur reviewer. Some of his favorite filmmakers include Michael Mann, Martin Scorsese, Tony Scott, Steven Soderbergh, Werner Herzog, Terrence Malick, and Billy Wilder, while favorite films include The Tree of Life, Goodfellas, Heat, Back to the Future, Fitzcarraldo, Schizopolis, The Counselor, and Enter the Void. His latest venture, Podcasting Them Softly, finds him tackling new ground as an entertainment guru, with a focus on filmmaker interviews and written analysis.