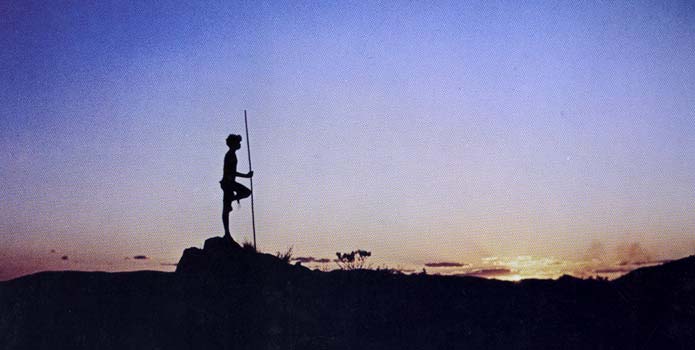

9. Walkabout (1971) – Nicolas Roeg

Country: Australia

The ‘60s and ‘70s wonderful decades for various countries producing new waves in cinema history, one such country that became somewhat of a powerhouse in the latter decade was Australia. Filmmakers were able to make films depicting confusion and post-colonial distress that made their films all the more unique. With breathtaking landscapes hardly seen in films until then, Australian cinema produced a few unbelievably good films. One such example is Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout.

Although made by a British director, Walkabout still manages to hold its own as an excellent statement on colonialism and the countries it has affected negatively.

Taking place in modern Australia, Walkabout starts with a bizarre bang when two English children are taken into the outback by their diplomat father who suddenly attempts to murder them, ultimately killing himself in the process. With no clear direction home, the two kids wander the wilderness until they are rescued by an Aboriginal boy who manages to understand the children despite their different languages and they wander the wilderness together in search of their home.

The film plays with the relationships people have in a very unique way, portraying what used to be seen as “savage” in the unfortunate eyes of Western audiences as human instead. Its progressive storyline and excellent camera work make the film a staggering work of beauty and social comment.

10. W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) – Dusan Makavajev

Country: Yugoslavia

Filmmaking in the Eastern Bloc proved to be experimental mainly due to the restrictions being applied by communistic governments and regimes. However, despite this, certain filmmakers managed to document life under oppression while also capturing certain liberties and mindsets that were indeed revolutionary. Dusan Makavajev’s experimental quasi-documentary/fiction film is a perfect example of communist politics clashing and ultimately fusing with a sexually-liberated population.

Consisting of multiple episodes, W.R. begins with an exploration of Austrian-American physicist Wilhelm Reich’s experiments with sexuality and the orgasm which then branches out into multiple narratives taking place in both Eastern Europe and the United States mirroring Reich’s experiments through sexual liberation.

In one episode, Tuli Kupferberg of the protopunk band The Fugs parodies Vietnam-era soldiers with sexual desire and weaponry while in another episode, sculptor Nancy Godfrey makes a cast of Screw Magazine cofounder Jim Buckley’s penis for posterity. Mixed in with the documentary footage is a tale featuring a Yugoslav revolutionary who tries to seduce a famous Soviet figure skater.

Despite being out there in terms of ideology and content, this film mirrored many experimental projects at the time, where the likes of Brakhage, Warhol, Anger, and Blank were producing experimental statements focused on liberal ideas, this film gives a European perspective on an interesting era in Cold War history.

11. Cries and Whispers (1972) – Ingmar Bergman

Country: Sweden

Already a powerhouse in cinema history with an extensive resumé, Ingmar Bergman shook his filmmaker foundations as an auteur with this melancholic elegy about life and death. Shot in color, Bergman was able to capture an unsettling realm surrounding two of his favorite subjects seen throughout his films: eros and thanatos (sex and death).

Set in the 19th century, Cries and Whispers follows three sisters living together in a lavishly decorated mansion. One of the three women is dying of cancer and is spending her last days in hopeful solitude while her two sisters attempt to get acquainted once again despite their coldness and distance to each other. In an episodic fashion the film relies on memories and contrasts them with stark color comparisons (most notably red) that add weight to the story and even turns the large mansion into a character itself.

This film takes the motif of Bergman’s cinema as pure horror cinema to its fullest potential as he depicts the cancer-ridden Agnes (played superbly by Bergman veteran Harriet Andersson) in the literal throes of death, where her pain is more unbearable to watch than the average slasher film. Alongside this sad narrative are Bergman’s standard metaphors of sexual repression and frustration as characterized by a couple of odd and disturbing scenes that poeticize mutilation and pain.

12. Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) – Werner Herzog

Country: West Germany

A great introductory film to whoever wants to explore the works of eclectic director Werner Herzog, Aguirre, the Wrath of God weaves an intricate tale of fantasy and social mayhem that solidified Herzog’s place in arthouse cinema ranks.

Set in the 16th century during Spain’s expeditions to the New World, the film follows a crew of Spanish Conquistadores led by the historical figure Pizarro in search of gold. When supplies run low in the treacherous Amazonian jungle, Pizarro sends a splinter group to scavenge for food and supplies.

Led by a by-the-book Ursùa, the group immediately falls on tough times, with mysterious deaths and rising hopelessness becoming commonplace. The deviant Aguirre (played by the also eclectic Klaus Kinski) begins plotting and setting himself up as the leader of the expedition, no matter what the cost.

Equal parts Heart of Darkness and Moby-Dick, Herzog’s film is a poetic and violent masterpiece that uses little dialogue and stunning visuals to tell its dark story.

Ultimately inspiring Coppola’s Apocalypse Now a few years later, Werner Herzog’s knack for realism and tough working schedules informed many a methodic director who would place the integrity of the picture over those acting and producing it anytime, even if it was he himself who would become the victim. One of the first collaborations Herzog made with Klaus Kinski, Aguirre, Wrath of God is a stunning example of 70s world arthouse cinema.

13. Fist of Fury (1972) – Lo Wei

Country: Hong Kong

As action cinema ran rampant in the United States in the 1970s, the debt most blockbusters owe to world action cinema is extensive. A great figure to begin with is Bruce Lee, the American-born Chinese action superstar who died at the height of his fame.

Also known as The Chinese Connection, Fist of Fury was a masterwork of action filmmaking as well as a bold anti-colonialist statement. Despite some of its overt racist undertones toward Japanese people (Bruce Lee refused to work with Lo Wei after this film was produced), the film makes brash independent statements on Chinese pride and tops it off by having Bruce Lee ultimately come out on top, albeit turning himself into a villain.

Set in early-20th century Shanghai, the legendary figure Chen Zhen (Lee) returns to his school to mourn the death of his teacher. Facing taunts from a local Japanese dojo, Chen wages a one-man war against the oppressing school and ultimately figures out his teacher’s death was no accident.

This film boasts some of Bruce Lee’s finest moments in martial arts cinema and helped skyrocket him to international fame and reverence as a near superhuman figure. Although he died the next year, this film sent shockwaves into the action cinema ether, influencing North American and Hong Kong kung-fu pictures as well as blaxploitation cinema leading up to the quintessential Enter the Dragon in 1973.

14. Lady Snowblood (1973) – Toshiya Fujita

Country: Japan

While Bruce Lee was beating down oppression with his fists in China, the Japanese added a female perspective to the mix with Lady Snowblood, a poetic masterwork in revenge-based action cinema.

This tale of 19th century vengeance is layered in its storytelling and sharp with its action. Detailing stories of rape, prison, training, and fighting, Lady Snowblood proved to be highly successful worldwide among various Japanese action characters like Sanjuro and Zatoichi.

The legacy of Lady Snowblood carried on in later decades, most notably in the films of Quentin Tarantino and features stunning visuals despite its extreme low budget.

Formally, the film follows a standard action pacing despite not being a samurai period film (jidai-geki). Empowering and violent, Lady Snowblood proved to take action cinema to parts unknown and helped influence the popular “girl revenge” genre from the 70s (with other films seen around the world like Sweden’s Thriller: A Cruel Picture [also 1973]).

15. The Harder They Come (1973) – Perry Henzell

Country: Jamaica

One of the most blatant explorations of urban decay and the dream of becoming what you want to be as a bittersweet victory, The Harder They Come proves to be one of the top rags-to-riches crime stories ever made.

Taking place in Kingston in the early 70s, the film follows Ivanhoe Martin, an aspiring reggae artist who travels to the urban core to find work. Recording a hit single (the titular “The Harder They Come”), Martin believes he has hit his mark, but corporate bureaucracy mingles with his dreams and ultimately leaves him with next to nothing for his output. In desperation, Martin begins selling drugs and is led downward into an unfortunate life of crime.

Taking the framework of classic 1930s and 40s gangster films, The Harder They Come adds a musical flavor to its narrative, making it an entirely unique piece of work. The story flows at a slower pace, only depicting violence at sporadic parts of the film. The tragic figure of Ivanhoe Martin mimics those of Depression-era James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson.

The film is made all the more effective with its cinematography and favor of location shooting rather than on-set shooting and real-life reggae artist Jimmy Cliff’s portrayal of Ivanhoe Martin is one for the books. Alongside these characteristic traits of the film, it also boasts a near-perfect soundtrack that sets it aside from most crime epics at the time.

16. The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) – Victor Erice

Country: Spain

Much like the countries of the Eastern Bloc sneaking subtle messages past censors, Francoist Spain also underwent such difficulties in the West. Under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, films and works critical of the state came under severe fire, and only a few works were layered enough to make it through and be seen and heard worldwide. One such film was Victor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive.

Set in 1940 in Castile, Franco’s regime is in full-tilt after winning the civil war and two sisters living in a manor cope with their distant parents and the politics of the time. After seeing James Whale’s Frankenstein, the youngest sister Ana, fascinated by the story of Frankenstein’s Monster, undergoes a spiritual transformation and fuels her further adventures in the future including exploring an old house, befriending a revolutionary rebel, and wandering into the forest alone.

This film plays many genres at the same time. While being a standard period piece, the story intersperses war chronicle, horror film, and psychological drama perfectly, making it creepy in its own sense. The near-silent protagonists show such innocence and longing for something new that it also becomes a heartwarming work.

Erice manages to balance these two traits with a masterful hand. A staple in Spanish cinema at the time (Franco was still alive when the film was released), The Spirit of the Beehive is a metaphoric statement concerning the conditions and times of an oppressive government.

17. Mirror (1974) – Andrei Tarkovsky

Country: U.S.S.R.

Already a popular influence in worldwide cinema with his medieval epic Andrei Rublev (1966) and his philosophical sci-fi hit Solaris (1972), Andrei Tarkovsky produced his autobiographical and arguably most poetic film of his career.

Breaking the boundaries of standard narrative structures, Mirror is fragmented and confusing at times, yet it is shot with such unspoken beauty akin to all of his work. Interspersed with sonnets of poetry written and read by Tarkovsky’s own father, the film takes on an epic meta-narrative chronicling Russia’s crippled history from 1935 until the 1970s as one child searches for a distant father. The film expertly plays with dreams and memories as the fragmented story jumps from various time frames, distorting the viewer’s perceptions.

While the narrator, Alexei is a major part of the film, the story mostly follows Alexei’s mother and wife (both played by the same actress Margarita Terekhova) and their struggles directly involved in Alexei’s thought process.

Although confusing, this film has garnered a high reputation among various filmmakers and has wedged Tarkovsky in the annals of auteur history as a top notch filmmaker, having his style mimicked by the likes of David Lynch, Béla Tarr, and mutually with Ingmar Bergman.