During the seven year occupation following the Second World War the American military imposed an authoritarian regime of censorship on Japan’s film industry, wanting it to effectively clone Hollywood’s contemporary oeuvre. The big money stateside lay in film noir and studios such as Nikkatsu and Toei, smelling profits to be made, quickly latched onto the crime genre as an opportunity to churn out hurried low budget stories of gangsters and cops.

Once the Americans had sailed home however the Yakuza subgenre morphed into a different beast entirely. New generations of renegades drew inspiration from an immense array of influences, from their native country’s rich cinematic tradition, French new wave and their own experiences of the devastating horrors of the global conflict and its aftermath.

This list begins before the war and spans six decades, intentionally composed so as to attempt to do justice to the thematic and stylistic variety of Japanese crime films. The films range from chivalrous tales of duty bound Yakuza to absurdist political polemics, via bitter struggles against corporate corruption and existential meditations. Many of them are violent, some supremely so, many are character driven pieces about family or love and all find something new and creative in what is often familiar terrain.

Directorially the first entry comes from Ozu, the master of classical aesthetic cinema. This list takes in his legacy through the polished beauty of Kurosawa but also the new wave game changers Oshima and Imamura and the boundless, surreal insanity of Suzuki, via a band of rebels, auteurs and luminaries.

In doing so it aims to represent both the old and the new: Imperial Japan in all its supposed glory, the subsequent society desperately surviving after a previously unimaginable and unheralded surrender and ultimately the contradictions of modernity as the post-war ‘economic miracle’ bought great wealth to a few and left others in destitution. The sense of a societal transition is strong within many of the entries as generations of directors sought to dissect their rapidly changing nation.

There is inevitably going to be a few notable omissions, so leave a comment below with anything you think has been unjustifiably overlooked and the author will be sure to commit yubitsume as a means of apology.

1. Dragnet Girl (1933, Yasujiro Ozu)

Yasujirō Ozu has had as much of an influence on the art of cinema as any other director, living or dead. Everything from his use of motifs and transitions to the height of his camera and pillow shots has been copied and emulated countless times. However his inclusion on a list of crime films may appear out of place, as his legendary status is a result of his later subtle, perceptive depictions of everyday domesticity.

Decades before Tokyo Story however he emanated bravado and aplomb with Dragnet Girl, an homage to the Western gangster flicks popular in Japan at the time. Noir tropes abound as fedora-ed, prize-fighter turned Yakuza Joji, stereotypical gangster’s moll Tokiko, ‘good girl’ Kazuko and naïve up and coming Hiroshi hang around pool halls and boxing gyms.

Yet Ozu doesn’t deal in clichés, his character’s complexities shine through clearly, even within the confines of silent film making. Although we are told Joji and Tokiko are ‘delinquents’ their emotions and desires are dealt with respectfully, reserving judgement in favour of engagement.

Dragnet is an extraordinary example of a young artist crafting their own technique and style. Ozu’s shots are uncharacteristically mobile and his sets bold and lively, with walls adorned with attention grabbing posters of contemporary American films and even Jack Dempsey. Not to take away from the effectual storytelling, but it is primarily requisite viewing due to its technical expressionism.

Indeed the film creates an enthralling underworld and what makes it even more fascinating is the director’s rejection of convention. This would become a hallmark of his later more acclaimed work but in a diametrically different fashion. Here the perceived infallibility of spatial logic is ignored and the camera glides down hallways and roads, at times purposefully and at others merely drifting.

Later he would religiously position scenes so as to be unobtrusive and even unambiguous, yet with Dragnet Girl we have an opportunity to see Ozu not as the iconic auteur but as a young director experimenting with his craft.

2. I am Waiting (1957, Koreyoshi Kurahara)

Kurahara’s 1957 directorial debut is somewhat of a forgotten gem but it expressionist lighting and tragic characters glitter, shining through the shade of tenebrous tones. Strolling the river front late at night restaurant owner and retired boxer Jôji stumbles upon the melancholic Saeko, who describes herself as a “canary that’s lost its voice.” A French influence courses through the film; Cognac is drunk, the opera Carmen plays on the radio and it would not be totally unjustified to draw comparisons between the two leads and Edith Piaf and Marcel Cerdan.

From their first encounter skeletons, both alive and dead, emerge from their closets, each telling its own sombre tale and eventually crescendoing into desolating tales of young hopefuls falling from grace. The boldness of Kurahara’s camera is just one of many hints of what was to come.

As a whole it is indicative of the post-occupation zeitgeist, heavily influenced by the West and yet distinctly Japanese, with traces of the nihilism that would permeate the country’s cinematic output throughout the sixties. It’s a film in which the darkness of midnight dominates the colour palette, a peaceful calm before the surreal storm of this list’s latter films.

3. The Bad Sleep Well (1960, Akira Kurosawa)

It’s testament to the incomparable talent of Akira Kurosawa that even his sometimes overlooked films are often masterpieces. The Bad Sleep Well is one such example and stands out on this list as not being concerned with organised crime syndicates but rather scandalous corporate greed.

Inspired in part by Hamlet, it sees a major construction company accused of corruption at the highest level. A face is given to capitalist greed as the film plays out as a conflict between the just and the bad. However as the title implies struggling against a privileged minority can be a futile task.

First and foremost Kurosawa’s film is a critique of the post-war Japanese corporate culture over the period described as the economic miracle. What is striking is just how bitter and vengeful it is. The audience is presented with a business subculture in which subordinates are fully expected to take their own lives rather than incriminate their guilty superiors by incriminating them.

Company men are driven to despair by the chokehold of bureaucracy and although they are suffocating they dare not loosen their ties. The central antagonists are not simply one or two corrupt presidents or vice-presidents, but the entirety of venal and villainous boardrooms. The battle lines are drawn as clearly as the film’s black and white tones, however the question of whether victory over such an enemy is even possible remains unanswered.

4. Pigs and Battleships (1961, Shohei Imamura)

Pigs and Battleships is a pivotal text in any attempt to contextualise post-war Japan. Decades later director Shohei Imamura would make a name for himself at Cannes and twice win the Palme d’Or but it was on this film that he cemented his position as an eminent figure in the New Wave moment. He did so by contrasting the old and new in Yokosuka, a port city which seemingly exists only to satisfy the seedier needs of the American sailors stationed there.

Pensioners work until their backs hunch, young women are harassed by GIs (or court them with the hope of a new life stateside) and the Yakuza bully and intimidate until they’ve squeezed every penny out of hapless families. The two early-twenty-something lead characters illustrate both the magnetism and inherent revulsion of the New Japan.

Haruko is caught between her mother who wants her to take up a sailor’s offer of ¥30,000 a month to be his bride and her love for Kinta, her somewhat goofy boyfriend who dreams of climbing the ranks of the mob he has become involved in (much to the dismay of his elderly father.)

Both are conflicted, simultaneously resenting the ongoing occupation of their country and treatment of its people while also envying the lifestyle the Americans all around them enjoy. Despite claiming to hate the “stupid yanks” Kinta wears a cap with a confederate flag and is fond of greeting people and saying goodbye in English, always with a cheeky grin.

Imamura himself said his films were messy, “because I don’t like too perfect a cinema.” Contrasting this with his former mentor Ozu’s painstakingly crafted elegance is vital to understanding the sixties’ ushering in of a new Japanese cinematic era. His camera pans and tracks through the slums and sordid Main Boulevard of Yokosuka, as his down-and-out characters stagger from one destitute situation to another, leaving countless forgotten dreams and failed schemes behind them.

5. Youth of the Beast (1963, Seijun Suzuki)

Seijun Suzuki is rightfully regarded as a renegade who crafted masterpieces from the most restrictive of circumstances. His status as a contracted B-movie director at the Nikkatsu Corporation beginning in the mid-fifties meant he was simply handed scripts he couldn’t refuse out of fear of losing his job.

The studio limited his pre-production to ten days, his shooting schedule to twenty-five and his post production to three. Yet even while working within these confines he was able to bring wild, fantastical and absurd ideas to the forefront of the Yakuza genre.

Kyusaku Hori, the infamously totalitarian Nikkatsu president, would come to resent him and he was warned he had gone “too far” and had to “play it straight”. His uninhibited expressionism would eventually lead to him being fired, blacklisted for ten years, glorified as a counter-cultural icon by the Japanese student movement and trumpeted by Wong Kar-wai, Jim Jarmusch and Quentin Tarantino, to name a few.

Pinpointing exactly when he began the transition from one of the many faces in a crowd of B-movie directors to cinematic nonpareil maverick is difficult, though Youth of the Beast, the first of two of his films on this list, is widely regarded as his first statement of intent.

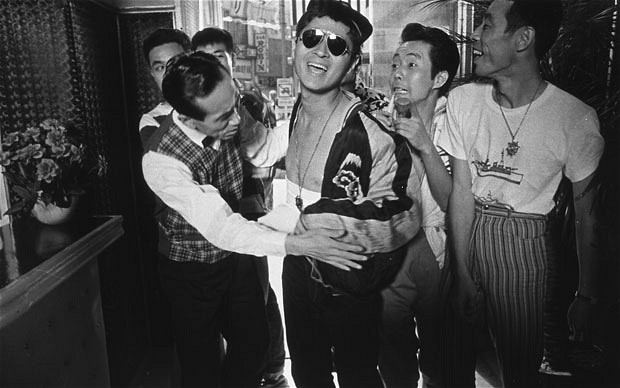

Frequent Suzuki collaborator Joe Shishido stars as Joji ‘Jo’ Mizuno, introduced as a cunning and ruthless mobster, who fights and muscles into employment with a Yakuza organisation. Just as audiences settle into thinking they’ve seen these organised crime clichés before, the twists and turns of a plot defined by its deranged and backstabbing characters unfolds through a succession of surreal and confronting scenes that flow majestically.

Never does it jarringly move from set-piece to set-piece, even when cutting from a pair of corpses to a cruising street corner bustling with teenage fun or silently showing us a go-go dancer appear from under a table to serenely entertain gangster and clients. Or even when a repulsively violent case of domestic abuse s out into a sandstorm. To give a further synopsis would only spoil the web of lies and betrayals that follows.

The strange and bold visuals that depict Jo’s struggles create a bizarre portrayal of Tokyo that would be frequently emulated but never matched. Kyusaku Hori wanted him to play it straight. Suzuki himself said that in his films “time and place are nonsense.” It’s really no surprise he got sacked.

6. Pale Flower (1964, Masahiro Shinoda)

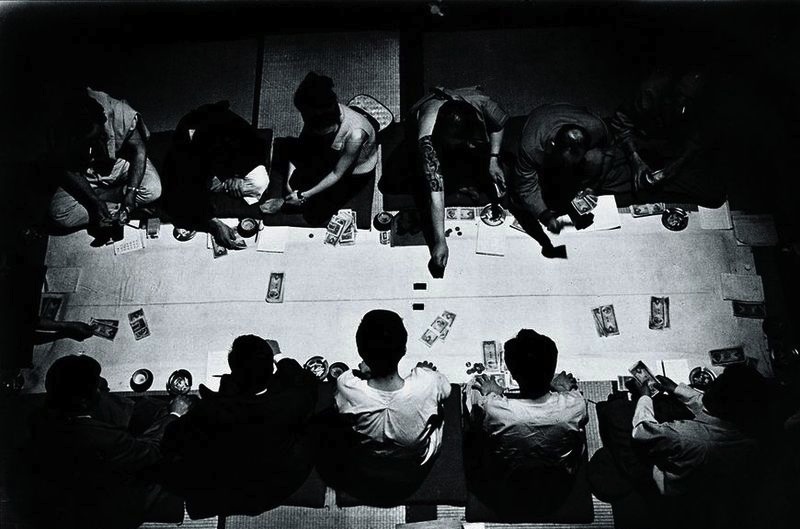

Shinodo’s Pale Flower aggrandized the significance and potential of both the bakuto-eiga (gambling film) subgenre and Yakuza films generally and yet at first glance its plot may seem platitudinous (a gangster recently released from prison becomes involved with a younger woman, gambling and violence when returning to his old life.)

In truth however it is a much more subtle and haunting picture. Muraki (Ryo Ikebe) goes straight from the slammer to his old turf to see not much has changed bar some few new faces at his local gambling den. Among them is Saeko, a young woman in what is ultimately a middle aged man’s playground. She stands out amongst the sweaty, balding and tattoed males she takes money off in high stakes games of Hanafuda, a Japanese card game that is central to the film’s ability to build tension.

Muraki quickly becomes beguiled by Saeko looking like, well… a pale flower, simultaneously withering and blossoming. The two enrapture each other and increasingly live one ill-advised raise away from both riches and ruin.

The two leads both contribute in an enormous sense to this film’s reputation as a turning point in Japanese New Wave. Mariko Kaga’s Saeko is at once innocent and dangerous, a giggling angel of death equally likely to bring humour and destruction. Ikebe is downtrodden, caught between the unbearable joy and confusion of the intensity of his newfound desires and an existential depression bought on by returning to the life that saw him imprisoned.

Sonatine would return to these themes decades later but it is difficult to imagine it or a significant portion of this list existing without Pale Flower.

7. A Colt is My Passport (1967, Takashi Nomura)

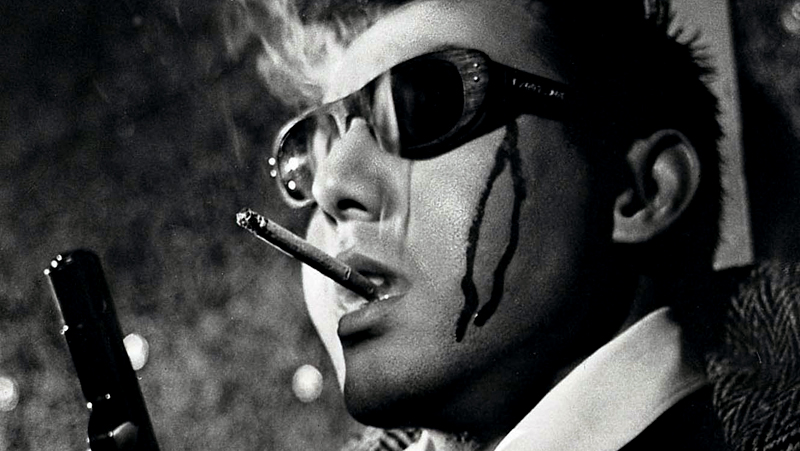

First and foremost an imitation of the cinematic traditions of American noir, Nomura’s genre classic proves emulation need not be a bad thing. It plays out like a greatest hits of the films it pays tribute to then compliments itself by oozing cool, with style gushing out of every shot.

This is of course in no small way due to its lead, once again the legendary Joe Shishodo. But it is also derived from the soundtrack’s blend of spaghetti-western and Japanese influences, furthered by the Sergio Leone-esque vast, open shots contrasted with extremely close-ups on character’s eyes.

Shishodo is Kamimura, a top contract killer accompanied at all times by his reliable partner Shun, played by Jerry Fujio. The two have a cast-iron bond, leading to Kamimura’s tragic love interest Mina to declare she is envious of their fellowship. After narrowly escaping a rival mob’s clutches after an assassination, they are forced into hiding. It quickly becomes obvious however that a quick and easy getaway is not a possibility.

This film is frequently held up as Nikkatsu at the peak of its powers and while it is not without faults (a range of secondary characters come and go without sparking any interest) two equally important factors keep it together. Firstly, the chemistry of the leading men. As Fujio plays a guitar ballad at Kamimura’s request the two allow themselves a brief respite and their mutually reliant relationship highlight’s both men’s emotional capacity, despite the ease with which they take the lives of others.

Secondly, the sheer, unadulterated style of Takashi Nomura’s direction, culminating in the climatic shootout. Our protagonist waits to see what fate has in store for him in an immensely empty landfill. It might as well be a scene from a New Mexico desert were it not for Shishido’s perfectly cut suit. He is the ultimate Japanification of The Man With No Name and he is the definition of kakkoii.