Some years ago, young filmmaker Colin Levy had the enviable opportunity to meet Martin Scorsese. The meeting itself isn’t as important (at least not to cinephiles) as what happened afterwards. Three weeks after the meeting, Scorsese had a list sent to Levy. On the list were 39 foreign films that Scorsese thought every young filmmaker should watch and learn from. Unsurprisingly, Germany, France, Japan and Italy are the most represented nations on the list.

Given Scorsese’s Italian heritage, it is interesting to focus on the Italian movies on the list. Scorsese has talked at length about the profound impact of Italian cinema on his art. The four-hour documentary, My Voyage In Italy, is well worth anyone’s time: a tour of Italian cinematic history given by a modern-day master.

He begins his journey with a personal account of watching Italian films on television with his family. Strange to think, but TV often showed Italian films back then, for the large community of Italian immigrants. For Scorsese’s parents it was a way of remembering and keeping in touch with their homeland.

Films such as Rossellini’s Rome Open City and Paisa had a profound effect on both Scorsese and his family, as they depicted an Italy undergoing the trauma of war. Indeed, many of the Italian films on Scorsese’s list depict an Italy coming to terms with historical trauma or uncertainty.

This in turn makes this list ideal for young filmmakers who feel incapable of either finding their voice or having it heard in the increasingly changeable world of cinema. Many of these movies represented bold steps in new directions, and their creators often faced hardship or censure as a result.

1. Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

Rome, Open City is regarded as the founding film of Italian Neorealism. Rossellini wanted above all to bring a new documentary realism to cinema. This was realised more through the conditions of filming than some intellectual dogma. Natural lighting, non-professional actors, scene durations determined by the amount and type of celluloid available, no studio sets,: all these things brought a radical spontaneity to the film, and to the neorealist films that followed.

Rome, Open City was filmed on location just two months after the Nazis had been driven out of Rome. The visible devastation seen in all the exterior scenes is real, adding to the distinct documentary feel of the film.

In fact, it had originally been planned as a documentary about a Catholic priest who had been executed for helping the partisans. But when an additional project about the children who fought against the occupiers was suggested, Rossellini and his co-writer – Federico Fellini – decided to make one film combining the two stories.

2. Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

American soldiers debark on the coast of Sicily. The sergeant chats with a young Sicilian woman who has guided him to a deserted mansion. He uses his cigarette lighter to show her his family photos. Suddenly he’s shot down by an German bullet. Carmella, the young Sicilian fires at random at the German soldiers and leaps to her death. So runs the first episode of Rossellini’s Paisan.

Released just a year after Rome Open City, Paisan is a very different movie about a similar theme: namely, the resistance against the German occupation of Italy. It’s divided into six episodes which highlight the diversity of the resistance. Several of the episodes feature American soldiers.

One particularly powerful episode follows an African-American on a drunken ramble around Florence. Not content with the mere novelty of featuring an African-American protagonist (unusual for the time), Rossellini comments on the problematic position of African-American soldiers: whatever their heroism, they will still still face the usual inequalities when they return “home”.

Again, Rossellini used an array of techniques to make the film as documentary-like as possible. Each episode is artfully inter-cut with newsreel footage. While six different writers (including Klaus Mann and Federico Fellini) wrote the episodes, much of the dialogue was improvised on set with the non-professional cast. This gives the film a unity that it may otherwise have lacked.

Paisan is one of Scorsese’s favorite films of all time, and his favorite Rossellini film. Its influence on later classics like Pontecorvo’s Battle Of Algiers is obvious.

3. La Terra Trema (Luchino Visconti, 1948)

La Terra Trema, or The Earth Trembles, is a gruelling almost 3-hour film set in a small fishing village in Sicily. In typical neorealist fashion, Visconti drew on the real people of the setting for his non-professional cast. After the film was released, the villagers were reportedly deeply grateful to Visconti for sharing their stories with the wider world.

Returning from the war, Toni, the eldest son of a Sicilian fishing family, has some ideas for the improvement of his family’s living conditions, but a combination of bad luck, naivete and – of course – socio-political hardship obstructs his path to success.

The film is divided into five acts, a structure surely inspired by Visconti’s training in theatre and opera. Indeed, the operatic dimensions of even Visconti’s most “realistic” films is a hallmark of his work. Rigorous attention is paid to the social structure of the town: the everyday working conditions of the fishermen are shown in extraordinary detail, with much of the footage having a documentary quality.

Some may even argue that it is a film that is endured rather than enjoyed. Grim realities are presented without sentimentality. The exploitation they face at the hands of the local merchants is an obvious mcrocosm of the broader exploitation Visconti saw as intrinsic to modern capitalism. But the undeniable sociological value of the movie never detracts from it’s power as pure cinema.

4. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

Bicycle Thieves has come to be seen as the jewel of Italian neorealism. It is also seen as one of the peaks of cinematic humanism. Like Rossellini, De Sica filmed on location, with no studio sets, and used non-professional actors. In fact, De Sica chose the actors to play the protagonists based on their similarity with the characters in the film. This is a practice that became de rigueur for political filmmakers.

Bicycle Thieves tells the story of Antonio, an unemployed father who gets a job pasting adverts on walls. When the bike he needs for work is stolen, a long and arduous search through the poorest parts of Rome begins. Antonio is accompanied by his young and loyal son, Bruno. This relationship has come to be seen as one of the most tender representations of a father-son relationship in cinematic history.

Antonio’s search for his bicycle is also an opportunity for viewers to gain valuable insight into the living conditions of Rome’s poorest citizens. Many Italians at the time looked unfavorably at De Sica’s movie. They felt that it portrayed Italy and Italians in a bad light. Viewers now see the detailed depiction of Italy’s grubbier side as a necessary step towards sympathy with people that cinema so often avoids.

Scorsese praises the film for its “powerful simplicity, a rare quality in movies.” A bare plot summary of Bicycle Thieves would suggest an unwatchably sentimental film. It is undeniably something of a tear-jerker, but the emotional responses are earned by De Sica’s masterful storytelling and characterization.

5. Umberto D (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

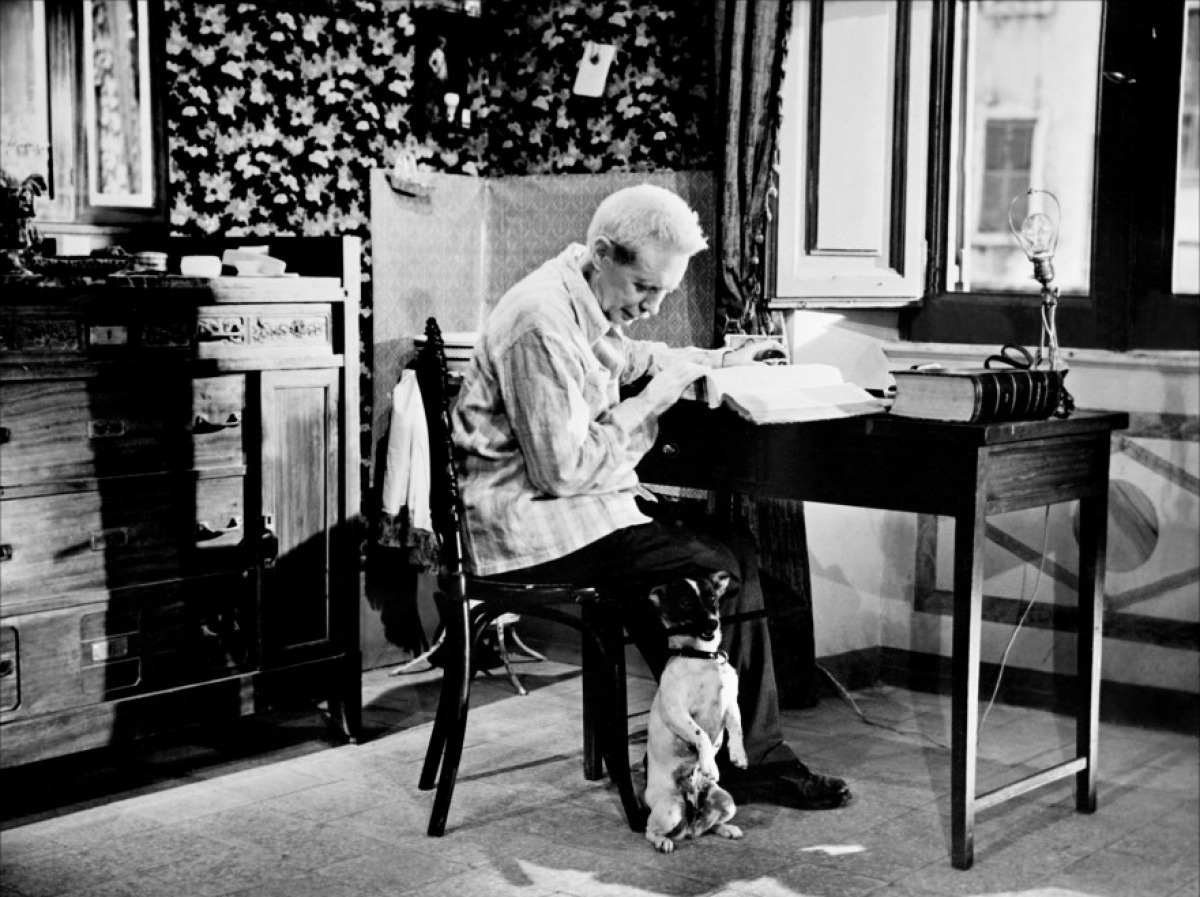

Umberto Domenico Ferrari is a solitary old man who can no longer survive on his miserable pension. Along with other similarly down-at-heel retirees, he participates in a protest but it it’s quickly dispersed by the police. Always accompanied by his dog, Flike, Umberto passes his days trying to gather enough money to meet his rent. He sells his watch, his books, and even he tries begging, but cannot bring himself to accept any charity.

Umberto D was something of a departure for De Sica, since his previous successes (Shoeshine, Bicycle Thieves, and The Children are Watching Us) had paid particular attention to child characters.

It is also a departure because there is less effort on De Sica’s part to elicit our sympathies. As Roger Ebert wrote: “”Umberto D” avoids all temptations to turn its hero into one of those lovable Hollywood oldsters played by Matthau or Lemmon.

Umberto Domenico Ferrari is not the life of any party but a man who wants to be left alone to get on with his business. In his shoes we might hope to behave as he does, with bravery and resourcefulness. Umberto doesn’t care if we love him or not. That is why we love him.”