6. Big Deal on Madonna Street (Mario Monicelli, 1958)

Big Deal on Madonnna Street is one of the classic crime capers, directed by Mario Monicelli and featuring an ensemble cast of Italy’s most respected leading-men (Marcello Mastroianni being the most famous). Learning of a minimally protected safe kept above an empty apartment, a band of hapless petty criminals start planning the perfect crime. Most of the film is spent on the mess that is the planning-phase.

The film proceeds like an clownish counterpoint to Jules Dassin’s famously stylish Rififi. The characters here are all amiable rogues, rather than hardened criminals. Indeed, it is one one of those crime capers where viewers really want the criminals to succeed, even if – or because – it’s perfectly clear that these criminals lack all the necessary skills to pull off such a crime.

This is not a familiar movie, in the sense that many people haven’t seen it. But when viewers get round to watching it, they’re sure to realize how often at has been borrowed from. It was remade as Crackers in the US, and movies like Welcome to Collingwood, Palookaville and Small Time Crooks are also heavily indebted to it.

7. Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960)

As with La Terra Trema, this is a film of operatic dimensions, despite its realistic settings and performances. It does not, however, rely on non-professional actors. Alain Delon plays Rocco. With his four brothers and his widowed mother, Rocco quits impoverished southern homeland for Milan. The brothers all embody different forms of masculinity: Vincenzo is a romantic, Simone is a brute, Luca is naive, Ciro is morally serious, and Rocco seems to embody a mix of all these characteristics.

While all five brothers try bettering their fortunes in various ways, the cohesion of the family unit is disrupted by Rocco and his brother Simone’s mutual desire for Nadia, a prostitute played by another familiar French actor, Annie Girardot.

The film received harsh treatment from the Italian censors. Visconti was forced to cut a particularly brutal scene of rape, and another scene of murder. The film was finally allowed to be released uncut in 1966. These scenes are indeed difficult to watch, but there is no question that they are necessary to the film’s overall effect and meaning.

The influence of this film was profound. Francis Ford Coppola chose Nino Rota to write the score for The Godfather series after hearing his music for Rocco. And Scorsese’s Raging Bull is clearly influenced by the Rocco’s boxing scenes.

8. L’avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960)

The ironically titled L’Avventura (The Adventure) is often said to be a film in which nothing happens. The main threads of the plot lack any obvious resolution, and the pacing is – as is usual for Antonioni – glacially slow. It was booed at its Cannes premiere, though it then won the Jury Prize. It is, then, a divisive film: merely tedious and alienating for many, and for others a timeless articulation of the loss of meaning and direction. Critics often place it among the top ten movies of all time.

Filmed within a tight budget in Rome, Sicily and the Aeolian Islands, it is ostensibly a film about the disappearance of a woman, and the subsequent search by her lover and best friend.

While the overall tone of the film is reticent, Aldo Scavarda’s cinematography seems to find analogies for the characters’ inner lives in their surroundings. Scorsese was impressed by the use of framing: the characters are usually framed off-centre, giving the impression “focusing your attention on the landscapes or the spaces around the people, echoing their sense of isolation and loss”.

While Scorsese initially found the film “puzzling and hard to decipher”, he became intrigued by “what I was not seeing. So I went to see it again and again.”

9. Il Sorpasso (Dino Risi, 1962)

Perhaps the least famous movie on the list, The Easy Life is carried to classic status by the chemistry of its two male leads, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Vittorio Gassman. Trintignant plays Roberto, a young and painfully shy law student, studying for an important exam. Looking out his window he notices Bruno (played by Gassman) and his stylish Lancia. Bruno needs to make a phone-call and Roberto offers him to come up.

Soon after, Bruno offers Roberto to come for a drink. However, there’s nowhere in the city to drink, because it’s the Sorpasso—everyone is away on holiday. Not to be put off by this, Bruno decides to take Roberto on a road trip into the country.side.

So begins a messy odd-couple friendship. As usual with this form of comedy, the plot is driven by the polar opposition of the two characters, and elicits sympathy at those brief moments when their common humanity is revealed.

While the movie is often seen as a commentary on Italy’s “economic miracle”, it is not an overtly satirical film. Both characters are treated with tenderness, and both actors were already known for their abilities to charm audiences. But the film does display a suspicion, especially considering it’s final scene, towards Italians’ increasing individualism and consumerism.

10. Before the Revolution (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1964)

Before The Revolution is ostensibly about a young man, Fabrizio, who falls in love with his aunt, Gina. As the title implies, however, it is a film with a much wider focus. Freely inspired by Stendhal’s Chartreuse de Parme (the film is set in Parma), the film is patient in its exploration of its characters’ inner lives.

Like many of Bertolucci’s films (right up to and including The Dreamers), it is an exploration of changes in political consciousness, and the consequent dilemmas faced by those undergoing the changes. While Fabrizio is inclined towards revolutionary Marxism on the one hand, his attraction to his aunt on the other seems to pull him towards bourgeois conformism.

The film was made when Bertolucci was only 23 years old. He claimed that he was going through inner struggles similar to those of Fabrizio. Scorsese was 21 when he first saw this film, at the New York Film Festival in 1964.

While impressed by many of the films at the festival – so Scorsese says – Bertolucci’s film “jolted him out of festival fatigue”, and he now considers it a “formative moment” in his cinematic education. If the film in summary sounds very dour, Scorsese confirms that it is in fact a “joyful” film about “a young man finding his voice”.

11. Blow Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Apart from several episodes of Paisan, Blow Up is the only English-language movie among these “Italian” movies. It’s included here because it’s very much an Antonioni movie, even if the setting and cast have come to be seen as an iconic representation of swinging London.

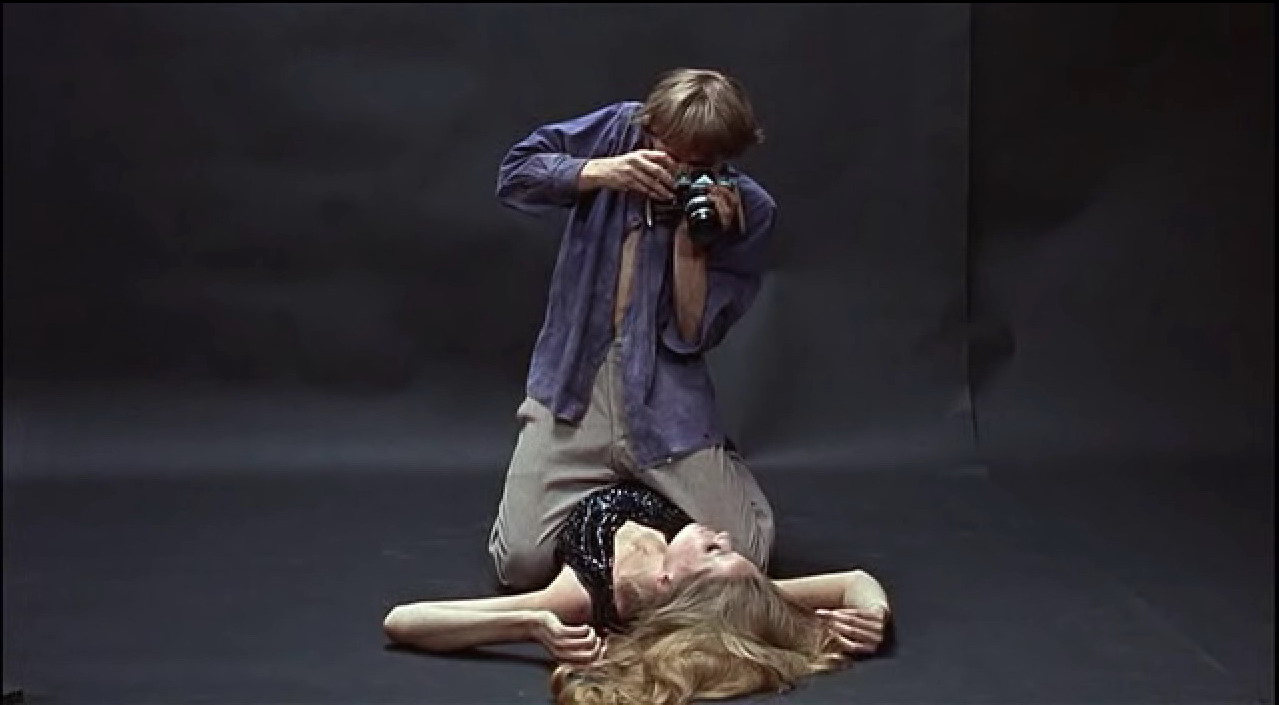

The plot focuses on Thomas (David Hemmings), a somewhat shallow and nihilistic fashion photographer, tirelessly buzzing back and forth between various art and fashion projects. His life seems to gain more meaning when he takes some photos of a man and woman in a park.

The woman follows Thomas back to his home and demands that he give her the negatives. He intentionally gives her the wrong film, and – his interest peaked – proceeds to blow up the photos and explore them in detail. After pouring over the photos for a while, the suspicion arises that he may have in fact photographed the scene of a murder.

While this may sound like the set up for a classic thriller, the movie is anything but. Indeed, Antonioni was famous for deploying aspects of the thriller genre (Hitchcock is referenced in L’Avventura, for example), but he always geared them to his own more philosophical interests. Thus, the movie is not so much about solving the crime that Michael may or may not have photographed, and more about the nature of images, truth and reality.

Author Bio: Ciaran is originally from Dublin, Ireland, but currently lives in New York. He has passionate interest in European and Japanese cinema – the old stuff in particular. The directors who have left the deepest impression on him are Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer and Marco Ferreri.