The connoisseurs of La-La-land have always been dreaming up spellbinding ways of hiking up the money tree and impressing millions. Sometimes it was through the glamorous sensuality of Dietrich and Munroe and, at others, it was the nerve-touching fair-ground attraction of computer generated worlds. Many times it was a knack for who-dunnits or who-killed-who-for-what?

Alongside these antics, there has always existed a string of introspective film makers who developed a taste for the fundamental: the human element and its visual translation in film. Contrary to Tinsel Town’s layers upon layers of fantasy fodder, these artisans of the minimal have explored suffering, frustration, loneliness, boredom, terror and submission by stripping down all unnecessary elements that would only seem to hinder their explorations.

This list is dedicated to those bare-bones films that strive to show the rudimentary in some way, that of the different moods and emotions invoked in the everyday; emotions that are not interrupted by the progression of plot devices.

10. The Match Factory Girl (Aki Kaurismaki, 1990)

The bleakest of Kaurismaki’s films, The Match Factory Girl follows the plight of a working class girl and a quiet isolation from her pallid surroundings. Though Kaurismaki employs a minimalism in his films, from laconic characters to undramatized narratives, this film is Kaurismaki at his most extreme.

The film is a vignette of Iris, her eating habits, submission to abusive parents, and her despairing attempts at introducing love into her monotonous setting. The film spends the bulk of its time quietly observing Iris through these habits.

Iris is inspired by Robert Bresson’s image of dissociated, suffering and sacrificial victims of everyday abuse. And like Bresson, Kaurismaki accentuates his characters’ solitude by near-robbing them of speech. Very little is spoken in The Match Factory Girl. Kaurismaki replaces the verbose with simple actions and visual cues, but which are actually revelatory.

The film opens with the process of machinery in a match factory churning out and boxing matches. By the time the films cuts to Iris and her inferior job of making sure the labels are glued onto the boxes, she is donning her usual pathetic face. Her character as a victim and her tedious surroundings as unsympathetic to her condition are already established early in the film without any use of verbalizing.

Kaurismaki’s vision of loneliness and despair is so well pronounced by eliminating speech and creating emotional gaps between his characters.

9. Mouchette (Robert Bresson, 1966)

Kaurismaki held Bresson in high regard for his minimal approach and his prioritizing of the human condition. Bresson’s Mouchette is probably the most minimal film on this list. The film simply follows a destitute country girl helping her family and receiving everyday abuse in a similar manner to Kaurismaki’s protagonist.

Bresson wanting to strip everything down to its essentials even led him to jettison acting itself. He would shoot any number of takes it required for a scene just to wear out his actors, so they could register no emotion. He called his actors “models” and saw the emotional register of acting as a device associated with theatre rather than film. Cinema, for Bresson, meant a strictly visual medium. In his Notes On Cinematography, Bresson stated that cinema is “…a writing with images in movement and with sounds”.

Bresson is well known for his extensive use of the close-up, drawing attention to detail.

His films, through this heightened awareness to the everyday, are emotional at a gut level. Like Kaurismaki, he shows events that are undramatized but reveals through them the primarily emotional. Writer/film maker Paul Schrader called it “Transcendental Style”.

Bresson expresses his character’s inner turmoil in Mouchette not through catharsis or intonations of voice but through this careful roving eye on Mouchette’s ordinary life. Mouchette is young. She goes to school and lives in a shabby house with dappled and dirty walls. Her mother is ailing. She helps out by feeding the baby.

In possibly the only scene in the film where Mouchette experiences a happy moment, a man takes notice of her in a fair ground and she subtly flirts with him by crashing her bumper car into his. Her father interrupts the flirtation and drags her off by the arm. All this unfolds without the use of words.

The ascetic director also explores the sexually frustrated world of men which sinks into violence. On a stormy night, a scene of poaching turns into a brawl between two hunters. The fight quickly turns into a scene of friendly consumption. One of the poachers later helps Mouchette when she is stranded in the storm and becomes a comfort for her from her everyday abuse at the hands of her father and friends.

Later, the same man in a drunken fever rapes her. These contradictory, almost schizophrenic, scenes provide an insight into male sexual aggression without the use of music or intonation.

Bresson achieves his rhetoric through movement, sounds, and relating an image to others. They invoke a kind of transformation for Bresson: “…the images, like the words in a dictionary, have no power and value except through their position and relation.”

8. Down By Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986)

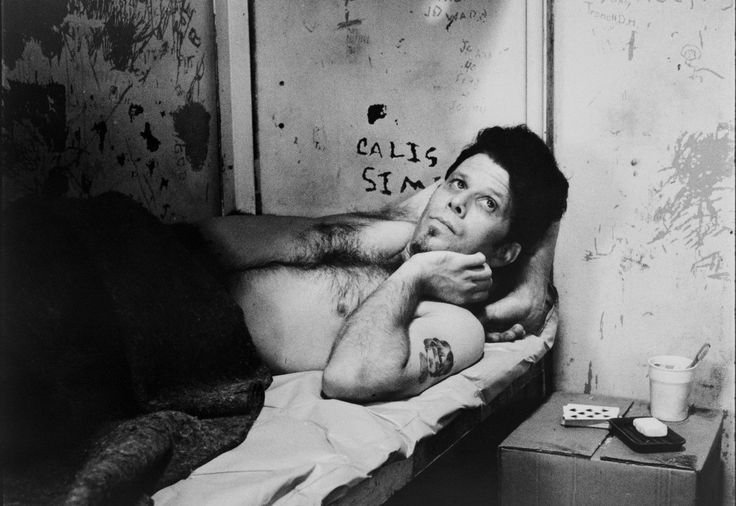

Jim Jarmusch, following in both Kaurismaki’s and Bresson’s footsteps, created great moments out of small narratives. Down By Law is ripe with these moments. A bulk of the film is set in a Louisiana prison, where three strange characters meet: a disc jockey, a pimp, and an eccentric Italian under-versed in English but carrying a book of English words and phrases (Bob, Jack and Zack).

Contrary to other prison films like the Shawshank Redemption, Hunger, or Papillon, Down By Law is not about the hardships of prison life. Prison is a simple point of intersection for the three characters played by Roberto Benigni, John Lurie and Tom Waits with his gin-soaked mumbling.

There are no great dramatic revelations in the film for either character concerning morality, the nature of violence or otherwise. Instead, the film quietly observes the three passing the time playing cards, arguing and talking about Walt Whitman.

The film takes its time to get to know the characters as they similarly get to know each other. At first, the three seem spent up and aggressive to each other, but very gradually become friendly through small talk. Bob the Italian, played by Benigni, plays his part as ice breaker between Jack and Zack.

Absurd moments, though, give the slowness of the scenes more flavour. When Zack asks why Bob is in prison, he answers: for killing a man. The harmless and quirky Italian turns out be a murderer. In another scene, the three circle around the room, yelling out one of the phrases out of Bob’s English book: “I scream. You scream. We all scream for ice cream”.

The narrative is dead simple and dead slow. The prisoners eventually find a way of escaping their cell, but at no point does it turn into a jittery, open-mouthed criminal-on-the-lam story. It imposes restrain on the characters and on the events. Robby Muller, with his slow camera, silently roves over the Louisiana bayou. They find a boat, row it till water gets to it and sinks it. They argue.

Finally, they find a solitary house in the forest where they meet Nicoletta whom Bob falls in love and stays with, while Zack and Jack part ways. The chain of events unfolds, similarly to Kaurismaki’s films, in the form of vignettes. Vignettes of small talk, subtle gestures and quiet lulls.

7. Under The Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

Under The Skin occupies a strange place in terms of genre. Like Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000), it mixes elements of social realism and that of the surreal; in the case of this film, the surrealism of science fiction. Scarlett Johansson is an alien femme fatale picking up men and seducing them into a black void. We get hints that she may be from another planet. The waspish Glazer, though, approaches the genre with austerity. To even call Under The Skin an alien film would be heavy-handed.

Glazer follows this seducer-with-no-name through Scotland while she picks up her men in a desolate Glascow. When she brings them to a black room full of inky viscous liquid that slowly swallows them up, the film turns into a vision of terror. A uniquely cinematic film, Under The Skin takes its cues through strange Kubrickan visual flourishes. Glazer uses the visual palette similar to many psychedelic science fiction films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Altered States.

The opening is an augury of things to come. A white cosmic light is brought closer and closer. Then, the formation of an eclipse and finally the close-up of an eye. This merging of the eye and the stellar is what Under The Skin is all about.

Instead of plot devices, customary to the sci-fi films of Christopher Nolan and Michael Bay, the film invites the eye into a world of sexual threat and identity crises through oneiric landscapes of engulfing liquid darkness and cosmic light. The visuals also receive their fair due in sound thanks to the screeching soundtrack of Mica Levi.

Glazer’s film doesn’t seem to be confined to any particular consistency or logic throughout. It doesn’t explain the alien’s needs to harvest her men nor does it explain her origins. Then again, the film is not plot-oriented and so needs no explanation. Jean Cocteau, master of the surreal and the oneiric, said that “An artist cannot speak about his art any more than a plant can discuss horticulture”.

The film is unapologetic in its refusal to expound on certain scenes. When the alien sees a man trying to save a drowning dog, he later drifts ashore at Johnasson’s feet. She lifts a rock and bashes it on his head. There is no moral compass devised for the character. The film is an intersection point for the interstellar, the sexual and the horrific.

The femme fatale does eventually develop some form of compassion for one of her victims, and as a result isolates herself in a forest. This form of compassion subtly unbridles our empathy for the alien when we see this transformation from clinical killer to victimized recluse.

Other than this narrative divide from the serial harvesting and later her forest isolation, we receive no direct input from the film maker, no map key to understand the whys of the film. This endows it with as much mystery as the beautiful alien clothed in human skin possesses.

6. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

Yasujiro Ozu, a master of subtlety and introspection, is known, like Bresson, for his asceticism. His films are usually simple domestic dramas about family, marriage and a Japan entangled between the traditional and the modern. Like Kenji Mizoguchi, his style was very much influenced by the aesthetic of certain Japanese traditions. He would use what is known as “pillow shots”, the filmic version of what in Japanese poetry is known as pillow words.

These are scenes of nature that separate a story or narrative. With Ozu, he mostly uses urban scenes of buildings, factories, and railway stations to move from one event to the next. Another Japanese cultural trait he appropriated in his films is his positioning of the camera at a very low angle to emulate that of the tradition of tatami seating positions. His cutting is also kept at a minimum as to not disrupt the careful mood of Ozu’s studied compositions.

Ozu’s camera, in most of his films as in Tokyo Story, rarely moves. It is carefully placed to quietly analyze the lives of his everyday characters. Tokyo Story is about an elderly couple who travel to the city to visit the home of their children and grandchildren. No violence or murder plots are peppered anywhere throughout the film.

Through this simple narrative, Ozu explores the nuanced interaction of the family household. The elderly couple are received with perfunctory smiles by their children and are eventually sent away by the children to a spa as they are too busy to host their guests.

The end of the film revolves around the grandmother’s death. One simple death, unlike films with body counts, is all Ozu needs to reveal the mindsets of his characters and intuit them through their simple actions and responses. When the family are dining, one heartless daughter, Shige, asks about her mother’s kimono and summer sash for keepsakes. The scene lacks any drama but through her subtle expressions, we are repulsed by the impassive daughter’s words in the aftermath of her mother’s funeral.

The film is never forceful in its emotional influence, and avoids any contrived sentimentality. It is inviting rather than manipulative in sharing an emotional exchange with its characters.

The elderly couple, whenever talking to their children, are dressed in oblique smiles that seem to cover up any distraught with their family’s emotional voids. This replaces the more conventional family arguments in other films which are not so subtle. Through Ozu’s steady-low camera, non-drama and visual stoicism, we slowly drift into the world of this flawed family dynamic.