The lofty reputation that precedes Paul Thomas Anderson’s name, including all the fervid rhetoric around his films, is simply unmatched by that of any of his contemporaries. For a whole generation that grew up between Blockbuster shelves, arguably no director filled the cinematic void left by the glorious seventies to a greater extent than PTA. His case was of a self-taught virtuoso—Hollywood’s equivalent of a Swiss army knife who wrote his own scripts and shot his own films with his personal troupe of actors. By the turn of the millennium, Anderson had already been anointed as the newest poster boy for American cinema before even hitting his thirties.

Ever since, critics and fans have long tried to dissect, scrutinize and put a label on his work, but PTA has proven time and time again not to be bound to any genre or style, but to the hefty expectations attached to his name. Licorice Pizza marks his first feature in over four years: a heartfelt homage to Southern California, and a bittersweet snapshot of young adulthood, love and the waterbed business. What better timing than now while we’re still hot on its heels to take a trip down memory lane and go through his entire filmography? Without further ado, here is every Paul Thomas Anderson movie to date, arranged from very good to best.

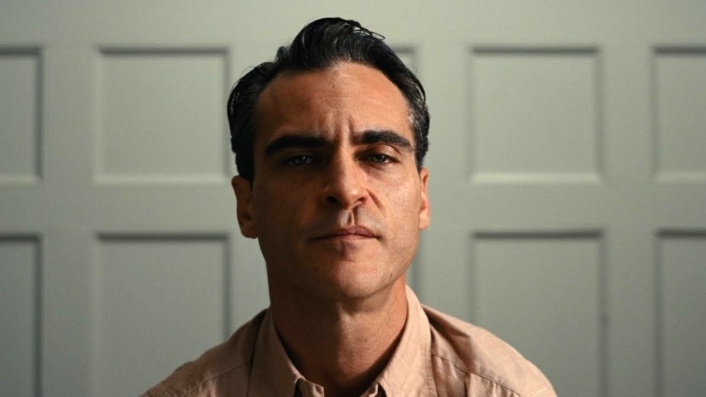

9. Inherent Vice (2014)

Ever since its release, Inherent Vice has been disregarded as the black sheep among PTA’s work, a rare misfire in his otherwise unblemished track record. The sour indifference that greeted his seventh feature has a lot to do with the fact that it needed to live up to two solemn and towering character studies like There Will Be Blood and The Master. For many, what we got instead—a farcical comedy disguised as a hardboiled noir—felt like a two-hour long joke without a punchline, more akin to canonical crime spoofs as The Long Goodbye and The Big Lebowski than it is to any of its predecessors.

Inherent Vice’s story is lifted almost verbatim from Thomas Pynchon’s novel, making it the first faithful adaptation in Anderson’s career (given the creative liberties taken in his oil-drilling masterpiece). Our white knight comes in the form of a goofy, laid-back private eye (Doc Sportello) who finds himself embroiled in a whirlwind of conspiracies and double-crosses all but heightened by his cannabis-induced paranoia. Accordingly, the film keeps throwing curveballs at every turn, thrusting us into a deliberately obtuse narrative that unfolds like a hazy dream, or rather, a markedly bad acid trip.

Beneath the film’s breezy playfulness, there’s a scent of melancholy hanging in the air, as if an era of freedom and idealism was slowly fading out only to make way for a bleaker, dark reality. That leaves our pot-smoking vigilante at a crossroads—the last bastion of a now-obsolete ‘60s counterculture forced to come to terms with Nixon’s America.

And still, arguably the biggest virtue of Vice is that it never attempts to make a grand statement, in fact the film wears its self-aware absurdism as a badge of honor. Though it may not rank as the most emotionally resonant work credited to his name, there’s simply no PTA film that rewards repeated viewings as much as this psychedelic detour.

8. Licorice Pizza (2021)

The title to Anderson’s latest film gives us a good hint at the intoxicating yet ill-fitting dynamic between its two lead characters. That a pubescent teenager and a twenty-something woman are drawn together would normally raise some eyebrows, but the story regards their free-flowing relationship, from chaperone duties to business partnerships, as an unlikely bond born not out of carnal desire—not reciprocal anyways—but emotional codependency.

Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) and Alana Kane (Alana Haim) find refuge in each other precisely because, on an abstract level, they both represent what the other yearns for. When it comes to Gary, an audacious high-school overachiever, Hollywood actor and part-time hustler, no challenge seems out of reach. Conquering a woman ten years his senior proves to be his biggest one yet. On the other hand, Alana overcompensates for her jaded disillusionment—reinforced in no small part by her erratic encounters with older men—by playing sidekick to Gary’s adventures. In his company, she finds the same freewheeling spirit and ambition she relinquished in adulthood, while momentarily keeping her existential angst at bay.

By returning to Anderson’s home turf (the San Fernando Valley) in his third foray into the ’70s, Licorice Pizza easily falls in line with the rest of his oeuvre. But within that framework, it comes off as the product of a seasoned director with nothing left to prove, devoid of all the gravitas and sense of urgency that defined his early output. Instead, this film seems more than content to go with the flow, fully lending itself to the characters, with broader realities like Watergate and the 1973 oil crisis looming large but barely intersecting with its self-contained narrative. That it should find itself at the near bottom of this list tells us more about PTA’s sheer consistency than any of its shortcomings.

7. Hard Eight (1996)

To reduce a body of work as eclectic and thematically rich as Anderson’s to one simple motif would be terribly shortsighted. That said, there’s one character archetype that keeps popping up in his work more frequently than any other—surrogate fathers. From Jack Horner to Lancaster Dodd, these paternal figures provide much-needed guidance and support to young drifters who often carry years-worth of emotional baggage and internalized trauma. Predating the former two is Sydney—a stoic, former gambler who takes a desperate man and a jaded hooker under his wing and shows them the in-and-outs of Vegas’ nightlife in Hard Eight.

When pitted against any of his subsequent efforts, Anderson’s debut can feel rough around the edges. Granted, the 25-year-old director was still ironing out his style and had yet to fully come to his own when he decided to reimagine his 24-minute short into a feature film. As such, Hard Eight lacks the operatic scope of Magnolia, the kinetic rhythm of Boogie Nights or the razor-sharp precision of The Master. But to this day, the film remains a valuable microcosm of PTA’s work, one that hinted at all his visual trademarks—including a bravado ninety-second long tracking shot—while laying out the groundwork to all the tropes and idiosyncrasies that would gradually become personal trademarks. Hard Eight also marked the first of many partnerships between Anderson and some familiar faces (Philip Baker Hall, John C. Reilly, Philip Seymour Hoffman) that would later grow into crucial collaborators in his career.

Sydney’s commendable tutelage is later revealed to be essentially motivated by selfish guilt. This paternal subtext drives forward the bulk of the narrative, but one could argue that the low stakes and austerity actually plays to the film’s benefit. Though it didn’t bestow Anderson with the same immediate acclaim as some of his peers (Tarantino, Linklater), for a debut saddled with studio meddling and a shoestring budget, Hard Eight proved to be a surprisingly solid steppingstone to his filmography.

6. Phantom Thread (2017)

Of all the rare qualities Anderson possesses, his range is perhaps the most defining. Whereas most of his contemporaries tend to circle back to their auteristic tropes and familiar story beats, PTA’s made a career out of reinventing himself. Ever since bursting onto the scene, he’s followed quite an unpredictable trajectory that seems to deliberately defy our perception of him as a filmmaker by forcing us to reevaluate it with every new entry.

Arguably no movie came more out of left field than his recent period piece romance, set against the sophisticated milieu of the European high fashion scene—especially for a director whose work is so inherently rooted in American ethos. Phantom Thread plumbs and deepens Anderson’s recurring themes of obsession and frail masculinity through its egomaniac lead, Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis), a renowned yet emotionally troubled dressmaker. The crux of the film lies in the abusive courtship and power struggle between Woodcock and his new muse, Alma (Vicky Krieps), whose chaotic presence threatens to disrupt his obsessively methodical routines.

Though Anderson’s chamber drama proved to be as venomous and exhilarating as any of his films, it does seem to follow a logical progression, at least in a formal aspect. Gone are the ostentatious camera tricks, from aggressive whip pans to extensive tracking shots, or the wall-to-wall needledrops that informed his early stage. These have given way to stiff, controlled framing where the camera is often reduced to a subdued observer, while the latter is now replaced by Jonny Greenwood’s understated (yet equally penetrating) music score. Still as present as ever though is PTA’s devotion to characterization and tongue-in-cheek humor (one could argue his best to date at that).

Ranking Anderson’s first production in foreign soil can be an endeavor as thorny as the film’s central romance. That one of the premier releases of the past decade fails to crack the top five in the present list feels all but criminal, but one should keep in mind that it’s only within the context of an embarrassingly stacked body of work. If his Californian ensembles were electrifying solo riffs, then Phantom Thread is nothing less than a masterful overture.