Since the very invention of cinema through to the present day, there seems to be no end to the artful and awe-inspiring visuals they create and the wonders they contain, lighting up living rooms, bijous, drive-ins, and multiplexes the world over.

Taste of Cinema’s tireless and exciting search for the most visually exquisite films “of all time” has been no easy charge, though several films stood out straight away. The assembled list presented here offers up films of dazzling depth, stirring symmetry, impeccable production design, gorgeous framing, and assured grace. Enjoy and please add to the discussion by contributing films we overlooked in the comments section below.

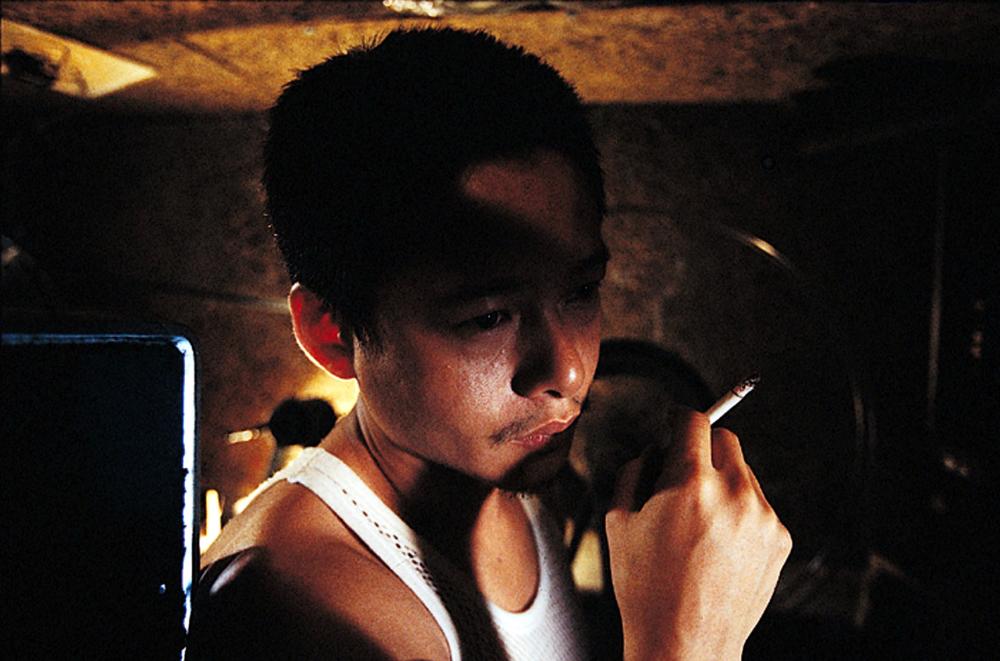

20. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

From one of the major players in New Taiwanese Cinema (next to Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang), Tsai Ming-liang details urban alienation with the deft eye of a master. Goodbye, Dragon Inn, set inside a doomed movie temple on the eve of its closure, demonstrates Tsai’s signature slow cinema approach of long fixed shots and abrupt eruptions of surreal humor––often courtesy of the expressive and paradoxically impassive actor and muse, Lee Kang-sheng.

In this film the Fu-Ho movie palace is populated by forlorn souls, both living and dead, wandering and wondering within the faded, once embellishing interior, ravenous for connection. Outside the Fu-Ho a torrential downpour drenches the streets of Taipei, establishing and underscoring a tangible yet allusive sense of ghostly melancholy that torments and troubles the picture in what is widely and rightly regarded as Tsai’s masterpiece.

19. Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

“The film’s role is to provoke, to raise questions that only the audience can answer,” said Koyaanisqatsi’s producer Godfrey Reggio, adding; “This is the highest value of any work of art, not predetermined meaning, but meaning gleaned from the experience of the encounter.”

Expertly lensed by cinematographer Ron Fricke, and buttressed by Philip Glass’s staggering score, this highly experimental documentary from Godfrey Reggio accomplishes quite a lot from, narratively speaking, very little. Taking its title from the Hopi word that means “life out of balance”, Koyaanisqatsi uses ravishing imagery and music to detail to the audience the ways in which mankind has grown apart from nature. The results are avant-garde, eye-opening, and regularly jaw-dropping.

Comprised largely of astonishing and extensive footage of elemental forces, and natural landscapes, Koyaanisqatsi also depicts scenes of modern civilization and technology in ways that are frequently startling but also quite stunning.

Jarring juxtapositions combine eloquently with Glass’s often hypnotic score and the results often feel like a religious experience in what may be the finest non-narrative film ever made. A marvel.

18. 8 ½ (1963)

Federico Fellini’s “eighth-and-a-half” feature is cited by many as his masterpiece, and while that may well be up for debate, this Oscar-winner is one of cinema’s most influential works, no question.

Made in response to the enormous international acclaim garnered for Fellini’s previous film, La Dolce Vita (1960), Marcello Mastroianni returns in a challenging central performance, this time as Guido, a famous filmmaker suffering from a creative block as he is at the precipice of his latest project, a big-budget sci-fi epic that could break him.

Accosted and harried at every ill-advised turn by fans, friends, the press, his producer, his screenwriter, his wife, his mistress, and his own mind, Guido retreats into fevered fantasy and unreliable memory, gradually coming to the realization that most inspiration is rooted in personal experiences.

Self-reflexive, strange, surreal, and incredibly self-indulgent, this comical and complex fantasia offers up a crazed compendium of Fellini’s entire body of work, and is simultaneously one of the definitive films about the process of movie-making. There’s no two ways about it, 8 ½ is essential cinema, and every frame is gorgeous.

17. Intolerance (1916)

D.W. Griffith’s highly influential historical masterpiece, Intolerance, is also a landmark marvel of sophisticated storytelling, and one of the most elaborate productions ever mounted. Braiding together four tales of oppression and enmity over a 2,000 year narrative, this is the showpiece that Pauline Kael called “one of the two or three most influential films ever made, and I think it is also the greatest.”

At three-and-a-half hours and with a cast of “thousands,” Intolerance, unfairly, flopped upon its initial release, but in later years was reappraised for the towering masterwork it truly is. With a complex structure, diverse locales (one story thread picks up in 539 BC, during the fall of the Babylonian Empire, another in contemporary urban America), and gobsmackingly colossal sets, Intolerance is the very definition of spectacle, and one of the finest and most imposing films ever wed to celluloid.

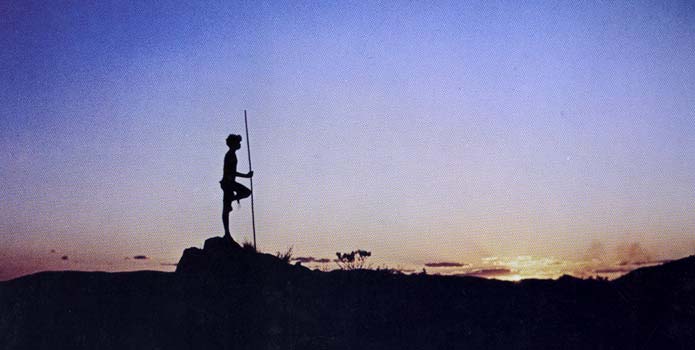

16. Walkabout (1971)

“A meditation about living on earth, which finds beauty in the way mankind’s intelligence can adapt to harsh conditions while civilization just tries to wall them off or pave them over,” praised Roger Ebert, who wrote about the film many times, accurately and enthusiastically proclaiming that “Walkabout is one of the great films.”

Powerful visual compositions with an almost religious intensity permeates Nicolas Roeg’s meditative, haunting, and at times eerily surreal story of survival in the Australian outback. Using James Vance Marshall’s 1959 novel “The Children” as a starting point, Roeg’s story involves a teenage girl (Jenny Agutter) and her little brother (Luc Roeg, the director’s son), who are left stranded in the wild after their father (John Meillon) suffers a breakdown and attempts to murder them before his own horrific suicide.

Aided by an Aboriginal boy (David Gulpilil) on his titular rite of passage journey, and Roeg’s exuberant visual dynamism, Walkabout is an exotic, inspiring, and absolutely unforgettable arthouse entry.

“One of the most original and provocative films of the 1970s,” wrote The Movie Guide’s James Monaco, adding that “Walkabout is set in terrain stranger and more awe-inspiring than that of any science fiction film.”

15. Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Co-written and directed by Italian filmmaking legend Sergio Leone, Once Upon a Time in America is, as Roger Ebert so succinctly phrased it, “an epic poem of violence and greed.”

This languorous and elaborate multigenerational saga of Jewish gangsters unfolds via flashbacks but begins in New York City, 1968, as aging David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro) returns to the locale of his crime career going back to the Roaring Twenties and the Dirty Thirties.

And while his longtime partner in crime, the hot-headed Max (James Woods) maybe ancient history, Noodles’s unresolved past and the people who populated it will be revisited with aplomb and with Leone’s unerring eye for detail, striking composition, and powerful imagery.

DP Tonino Delli Colli strikingly lenses the film, with particular care given to the recreation of New York’s Lower East Side, with a brilliant score from Ennio Morricone that seems to effortlessly add to the technical beauty on screen. It’s dazzling in so many ways.

As atmospheric and elegiac as anything Leone’s ever done, Once Upon a Time in America was the longest film of Leone’s CV, and sadly, it would be his last (he passed away shortly after production wrapped on the film). But, be that as it were, the film makes for a fine valedictory film; it’s a haunting evocation of America that’s both startlingly symbolic, and artfully introspective.

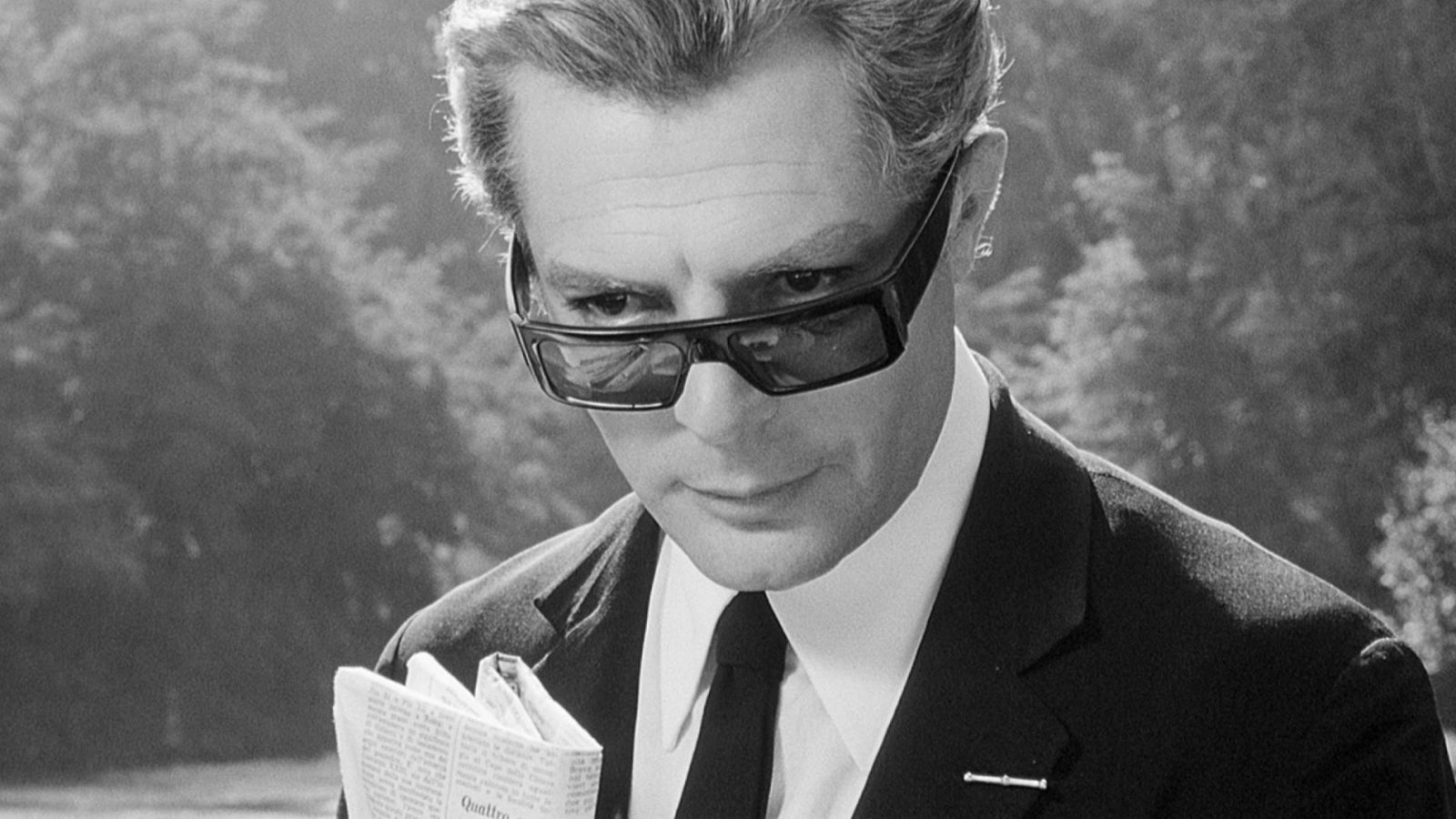

14. The Conformist (1970)

What might be the supreme achievement of director Bernardo Bertolucci — and while we’re here, of masterful cinematographer Vittorio Storaro — The Conformist is a glory to behold, and is one of cinema’s most visually beautiful works.

Jean-Louis Trintignant is brilliant as Marcello Clerici, a secret police in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy in this searing, psychologically-complex study of sexuality and politics. Marcello is young man who becomes a Fascist in order to suppress his homosexual tendencies, making him the tragically titular “conformist”.

The noir-like plot (written by Bertolucci but based on the 1951 novel by Alberto Moravia) artfully unfolds as a series of flashbacks (and flashbacks-within-flashbacks) has Marcello sent on a mission to assassinate his former mentor with shattering consequences.

The overpowering opulence of the staggering visual design — expressive lighting, lavish Art-Deco decor, elaborate tracking shots, sumptuous costumes — echoes the great Hollywood studio cinema of Max Ophüls, Josef von Sternberg, and Orson Welles, and all that that entails.

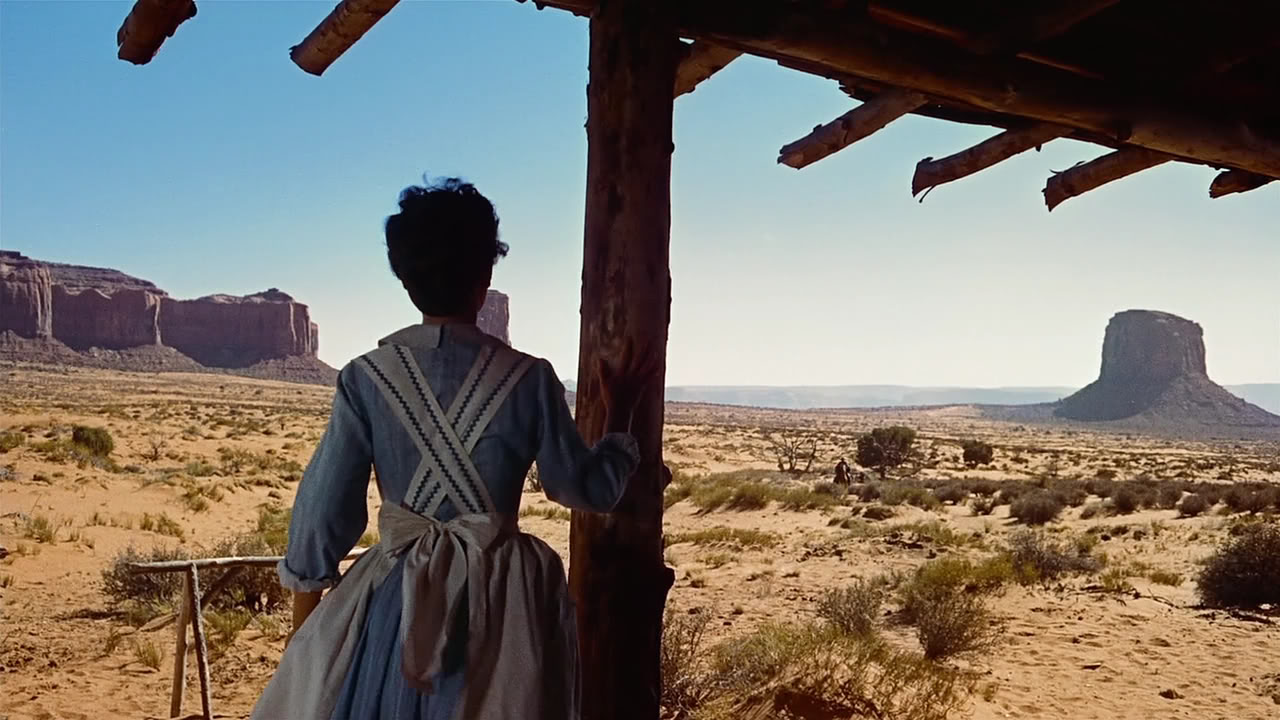

13. The Searchers (1956)

Not only is John Ford’s The Searchers one of the cinema’s greatest Westerns, it is, as Martin Scorsese put it, “[a] great work of art.” Shot on location amidst the gloriously staggering vistas of Utah’s Monument Valley, John Ford’s magnificent landmark “…contains scenes of magnificence, and one of John Wayne’s best performances,” raved an enraptured Roger Ebert.

Following the embittered and broken outsider Ethan Edwards (Wayne, whose catchphrase here, “That’ll be the day,” was the inspiration for Buddy Holly’s classic hit song), The Searchers lays forth an epic odyssey as our anti-hero searches for the Comanche Indians who kidnapped his niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) and also massacred the rest of his brother’s family. At Ethan’s side on his obsessive quest is Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who is part Cherokee himself, adding more conflict both inner and outer to the simmering pot.

The Searchers’ conflicted politics are just one aspect of its many fascinations and Ford’s classic film has exerted an impressive and powerful influence on many leading filmmakers; George Lucas’s Star Wars saga, Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, and the Wim Wenders classic Paris, Texas, are amongst the movies in its considerable debt.

12. The Master (2012)

A polarizing but prominent director (as so many on this list are), Paul Thomas Anderson is, as Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers suggests, “…a rock star, the artist who knows no limits.” Travers goes on to say rather astutely that “ [The Master is] written, directed, acted, shot, edited and scored with a bracing vibrancy that restores your faith in film as an art form, The Master is nirvana for movie lovers. Anderson mixes sounds and images into a dark, dazzling music that is all his own.”

Anderson’s The Master presents a powerful and precise portrait of a troubled, violent, and often soused drifter named Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), suffering from shellshock after WWII he eventually, in 1950, runs into the charismatic cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Mentoring Freddie, Dodd brings him into his religious movement, the Cause––a simulacrum for Scientology, and Dodd of L. Ron Hubbard.

A compelling, challenging, maddening and invigorating film, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. (who won many awards for his fine work here), presents a fluid and unbroken chain of high contrasting imagery. This is one haunting and lamentable honey of a picture.

11. The Third Man (1949)

Something of a compendium of film noir technique, Carol Reed’s The Third Man is, as New York Times movie critic Bosley Crowther wrote “a brilliantly packaged bag of cinematic tricks, [showing Reed’s] whole range of inventive genius for making the camera expound. His eminent gifts for compressing a wealth of suggestion in single shots, for building up agonized tension and popping surprises are fully exercised.”

Set in postwar Vienna, and starring cinema legends Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles (Trevor Howard and Alida Valli also turn in strong performances), even this strong a cast is dominated by the atmospheric use of Robert Krasker’s impressive expressionistic black-and-white photography.

With distorted Dutch angles, harsh lighting, and authentic locations, paired with Anton Karas’ iconic thematic score, this is the Cold War made manifest as a cynical, sinister, and sumptuous spectacle.