Filmmaking is a focus on the observation of human nature, and while there are films that are great for the critical approach they take toward humanity, displaying its darkest and cruelest side, there are also films that are great because they way in which they display the highest of our species. By creating moments of understating and displaying actions of kindness, these films move us to the core and allow us to understand each other better.

Here is a list of 10 films with a humanistic approach, that, while being complex, also displays the best and most bright side of humanity.

10. I, Daniel Blake – Ken Loach

The winner of the Palme d’Or at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, the latest film directed by English director Ken Loach and written by his collaborator Paul Laverty displays a harsh and kind portrait of the hardships in the life of Daniel Blake (Dave Johns).

Daniel must face the indifference of the English bureaucracy that denies him a support allowance, even though his doctor found him unfit for work. He has to face a world of confusing procedures that he sometimes cannot understand, and which require him to use a computer, even though he has never come close to one.

Through the film, Daniel interacts with other characters who are also facing hardships, and he displays to them constant acts of kindness. A single mother and his daughter are the family that Daniel decides to have when he helps them and gives them all he can.

The portrait that Loach creates of these struggles is deeply moving due to the impotence of the characters and the kindness in them. He displays the dehumanization of bureaucracy while it pays homage to the humanity in human relationships that the characters show to one another.

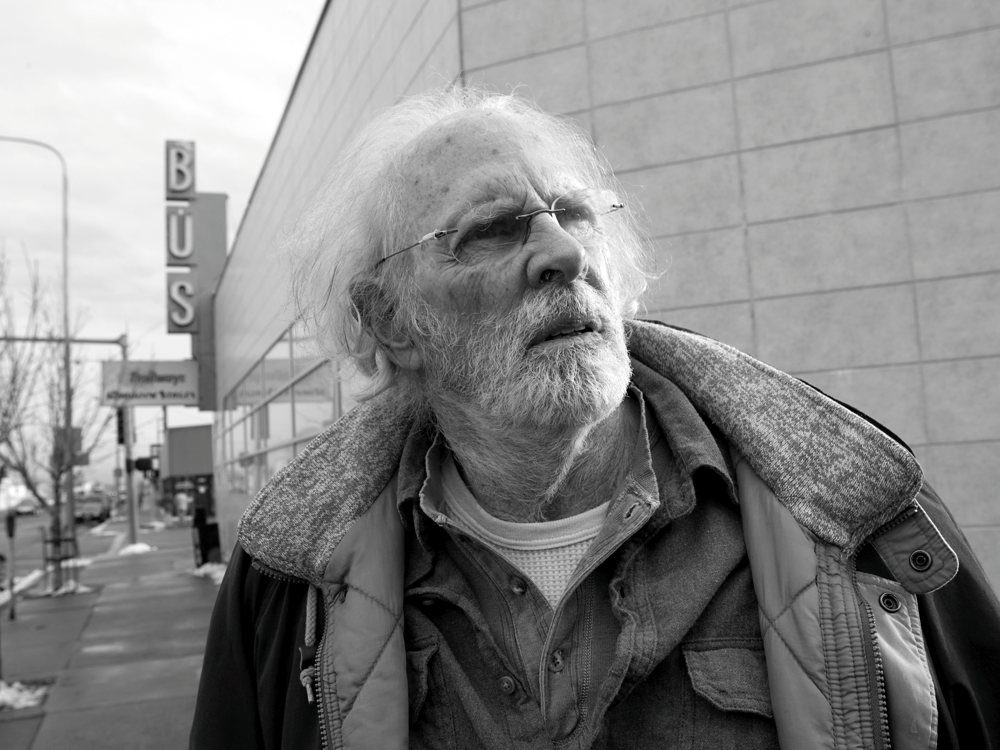

9. Nebraska – Alexander Payne

The black-and-white film “Nebraska” by Alexander Payne film, starring Bruce Dern and Will Forte, was released in 2013 and received international acclaim, becoming an instant modern classic.

The film displays the trip that Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) and his son David (Will Forte) took from Montana to Nebraska. The trip is done in order to claim an obviously fraudulent prize of one million dollars that Woody believes he has won, and to which David decides to drive after dealing with the stubbornness of his father. Even though David is convinced that the prize is not real, the trip makes him constantly interact with his almost catatonic father and his past.

The father and son pass through Woody’s hometown where they face the family and people of his past, at the same time that David reflects in his unsatisfactory life. Through the journey, David starts seeing beyond the stubbornness of his father, and beyond the initial burden as which he perceives him.

The acts of kindness and egoism are realistically portrayed in “Nebraska,” as the young son finally understands the position that his father is in. This builds up to a wonderful and moving ending, after Woody understands that the prize was not real, in which David gives back his dignity to his father, just for one moment.

8. L’Enfant – Dardenne Brothers

The winner of the Palme d’Or in the 2005 Cannes Film Festival, “L’Enfant” is one of the most acclaimed films by Belgian filmmakers and brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. The film displays Bruno (Jérémie Renier) and Sonia (Déborah François) experiencing a series of misfortunes after Sonia gets pregnant and Bruno decides to sell the baby; Sonia is 18 years old and Bruno is 20.

The film develops Bruno and Sonia with such care and respect (two characteristics of the Dardenne Brothers) that the actions of Bruno are not condemned nor absolved; instead, they are understood as the result of the lack of maturity that Bruno has for facing adult life.

This Belgian film is a kind and honest portrait of a youth that Alain Badiou describes in one of his latest bocks, “La vraie vie: Appel à la corruption de la jeunesse.” Here is a youth that never had a concise threshold toward adulthood and thus is facing the world with the innocence of a child.

There is no evil within Bruno, and as he understands the implications of his actions, he tries to untangle the mess. This leads to a moment of understanding between him and Sonia, seeing Bruno in the vulnerable and impotent position that he is.

7. The Other Side of Hope – Aki Kaurismäki

Released in 2017 in official competition in several film festivals, “The Other Side of Hope” was presented by Kaurismäki as the last film that he would direct. Through his great career, Kaurismäki has created a unique and personal world with his films in which the dialectic between alienation and communication can be often seen.

This film was released within the frame of the European refugee crisis: it displays Khaled (Sherwan Haji) as a Syrian looking for asylum in Helsinki, and Wikström (Sakari Kuosmanen), a Finnish middle-aged man who decides to leave behind his family and buy a restaurant.

The film displays the interactions between these two profoundly different men in the characteristic style of Kaurismäki, a powerful combination between humor and melancholy. The film displays a realistic treatment towards its complex characters whose differences make their relationship initially conflictive.

With the empathy of Kaurismäki we can also see moments of kindness and earnest communication between two characters. These moments are crafted organically and without omitting the conflict in which they are involved, and this is the way they became so great.

6. After the Storm – Hirokazu Koreeda

One of the most moving dialogues in “After the Storm” by Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Koreeda is, “How did it all end up like this?” This is a dialogue that reflects the emotional state of Ryota (Hiroshi Abe) through the film.

“After the Storm” is a portrait of this middle-aged absent father who has become a low-paid private detective after the failure of his once-promising writing career. Ryota’s relationships are tumultuous; he is not entirely on bad terms with his former wife, but she is constantly annoyed by him. Ryota also has to face the expectations of his young son who still idealizes him, but who ends up discovering his father is also a flawed human.

The interpersonal conflicts in the life of Ryota are channeled into the night he has to spend in the house of his mother with his former wife and his son. They become trapped in the house due to a storm that impels them from returning to their homes.

The condition of sharing an apartment during a whole night creates silent yet moving confrontations between Ryota and his family, but most importantly between Ryota and himself. His relationship with his past is materialized in an old play park where he, his son and his wife end up hiding from the storm. This is a film that continues with the tradition of Yasujirō Ozu to create moving and humane films out of day-to-day characters and problems.