Ready or not, here comes another batch of 20 movies which fit the weird (strange / surreal / obscure / fantastique / experimental / unorthodox / open-minded etc) “mold” and need a little bit of “word of mouth” support for different reasons.

As the title suggests, they are all released during the 21st century, whereby the rule of “at least one title per year + chronological order” is applied. Similarly to the latest list by this writer, a few short and animated films worthy of wider recognition are included as well, for some fun and diversity.

1. Long Dream (Higuchinsky, 2000) / Japan

If a dream could last for infinity, what would happen to the dreamer? This logic-defying question is given a weird answer by the Ukrainian-born Japanese director Higuchinsky of “Uzumaki” fame in his made-for-TV feature debut that is also the adaptation of Junji Ito’s manga.

A low-budget affair, “Long Dream (Nagai Yume)” is set in a hospital during the course of a few nights. It revolves around a celebrated neurosurgeon, Dr Kuroda, and his colleague, Dr Yamauchi, who attempt to cure a young patient named Tetsuro Mukoda who complains of increasingly long dreams. At the same time, another patient, Mami Takeshima, who’s admitted for treatment of a benign tumor experiences a heightened fear of death.

The poor girl believes that Tetsuro is “shinigami” and it’s no wonder she does, considering his grotesque transformation caused by the peculiar malady. And Dr Kuroda who initially expresses doubt begins to suffer hallucinations involving his deceased girlfriend Kana…

As silence and cacophonous score intensify the mystery, Higuchinsky establishes a Twilight Zone-like atmosphere, making the most of the limited resources, especially as the cinematographer with a keen eye for lighting. Even when his cast is overacting (in that special Japanese way), he doesn’t loosen his grip over the helm.

2. Claire (Milford Thomas, 2001) / USA

In his (most unfortunately) one and only offering, which is inspired by “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Taketori Monogatari)”, Milford Thomas pays a loving homage to the silent era movies. Shot on a 35mm hand-crank camera, “Claire” is an hour long (queer) deconstruction of a fairy tale which looks and feels like a precious relic of the past.

Taking us back to a modest farm somewhere in the American South of the 20s, it opens with a wishful dream of an old man, Josh, who lives with his gay partner, Walt. What follows is a short introduction to the couple’s day to day routine and the sudden appearance of a tiny girl, Claire, in a shimmering corn husk, during a moonlit night.

As the story progresses (to the next morning), she grows into a beautiful young woman who attracts the attention of a rich “harpy” and, particularly, her son Richard. From that point on, there are hints that the rural idyll is going to be shattered…

A labor of love for the cinema of yore, with “cardboard, wires and all” favored over CGI, “Claire” delivers plenty of mesmerizing black & white (as well as indigo & white) eye-candy. Addressing the themes of transcendental love, grief and LGBT parenting, it flows like the heroine’s milky tears and it’s accompanied by the euphonious score performed live by the 11-piece chamber orchestra conducted by the composer Anne Richardson. The audience’s laughter and applauses give the impression of being in some old theater before “talkies” arrived.

The fans of Guy Maddin’s oeuvre should definitely check this one out.

3. The Tale of the Floating World (Alain Escalle, 2002) / France | UK | Japan

“Life is the beginning of death.”

A boy fishes in the bluest of waters. Prior to the eclipse, a long-haired woman in red kimono plays koto. In the aftermath of tsunami and atomic bombings, naked butoh dancers perform a mourning-like act. Deeper in the past, a flaming samurai battle occurs…

The best way to describe Escalle’s “The Tale of the Floating World” is a Westerner artist’s blurred vision or rather “abstraction” of Japan. Within the 24-minute time frame, a viewer is treated to the poetic, associative imagery that looks like a cross between ukyo-e, Irina Evteeva’s animations and Zbigniew Rybczyński’s “Orchestra”.

Decidedly non-narrative, this CGI-enhanced phantasmagoria gets progressively darker, with “fresh” colors and ethereal melodies replaced by the drab tones of gray and ominous dissonance. But, even at its most unsettling, it retains its unusual beauty.

4. The Warriors of Beauty (Pierre Coulibeuf, 2003) / France | Belgium

Opening with a frantic knight trying to kill an invisible dragon and ending with the disappearance of a blind man who previously claimed to be a prophet, Pierre Coulibeuf’s experimental fantasy also involves a barking dwarf and a bride searching for someone or something (hint: it’s not a husband, nor it is a bouquet).

In the series of offbeat vignettes which combine strange juxtapositions, Dadaist incongruities and the most varied surprises, the aforementioned French (post)modernist transposes the controversial Belgian artist Jan Fabre’s freakish nonsense-performance onto the celluloid film.

As if in a trance, flexible “dancers” writhe, wiggle, transform into the ambiguous symbols and leave their souls on the provisory “stage” amongst the decrepit walls, in the static, yet attractive tableaux vivants captured by the keen eye of DP Yves Cape of “Holy Motors” fame. Life and death and the in-between exist simultaneously and don’t exist at all.

Delightfully pretentious in both amusing and perplexing way, this witty, twisted and somewhat sardonic film never outstays its welcome. Alluding to the freedom of artistic expression, it is like a revolutionary game without any rules. A sticky, entomophobic provocation, it could also be labeled as a spiritual sequel of Makavejev’s “Sweet Movie” or even Barney’s “The Cremaster Cycle”.

Absurd as a dream, it has the quality of a Boschesque ritual in a dead-end labyrinth of inspiring perversions.

5. Tsuburo no Gara (Masafumi Yamada, 2004) / Japan

From the very beginning, “Tsuburo no Gara” (at this point, there’s no English/international version of the title) grabs you with its thick, claustrophobic atmosphere. In some kind of an underground tunnel, we see an old man in black who sits on a chair, holding a huge shell in his right hand. Only the sound of water drops falling can be heard. A little boy appears and closes his ears.

Following this enigmatic prologue is the industrial-themed intro (featuring snails) and then, the awakening of a nurse with a bad scar on her thigh and a patient who sports a strange mechanism along his backbone. They are trapped in a ramshackle hospital room – she wants to escape and he seems to be reconciled with the current situation.

Exactly who, why, when and where are they is unknown and Masafumi Yamada refuses to offer any answer to the obscure and minimalistic narrative of his feature debut. Sparse dialogue and lucid hallucinations are all the parts of the puzzle we get.

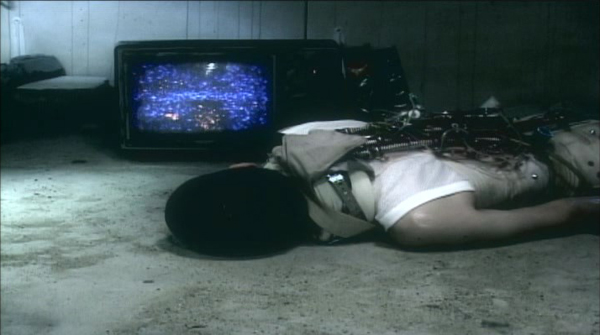

Deliberately paced, this arthouse cyberpunk mystery is the exact opposite of Tsukamoto’s “Tetsuo” or Shozin Fukui’s equally rabid “Rubber’s Lover”. It makes you almost feel the dust, dirt, stuffy air and the characters’ sweat in the numerous close-ups, accompanied by moody drones and the noise of TV static, clock ticking and metal clanking.

As a producer, director, writer, editor and cinematographer, Yamada is in full control of the film, providing “dreamy catharsis” in its conclusion.

6. Princess Raccoon (Seijun Suzuki, 2005) / Japan

“… for all its sophisticated razzle-dazzle, this goofball gesamtkuntswerk connects back to the origins of movies through slapstick, pantomime, melodrama, and magic.” (Nathan Lee, The Village Voice)

If you ever dare to let Suzuki’s testament work wash over you, you will probably wonder: “Is it possible that something so jovial and youthful, intentionally kitschy and wildly imaginative comes from the mind of an 82 year old man?” Having a whale of a time, he creates a unique genre and media mash-up which makes even “The Happiness of Katakuris” seem conventional in comparison.

A spiritual successor of “Pistol Opera”, “Princess Raccoon (Operetta Tanuki Goten)” takes us back to the alternative feudal Japan, probably in a dimension parallel to Fellini’s “Satyricon”. A vain king, Catholic witch, young prince, Chinese princess and ninja who goes by the name of Ostrich Monk are the main characters in the story which is based on the Japanese folklore and involves the search for the Frog of Paradise.

Suzuki draws inspiration from various sources – Shintoism, Buddhism, Christianity, Nō and Kabuki theater, “Romeo and Juliet”, Baroque, Dadaism, Surrealism and Socrealism, Broadway musicals, pop-art, camp, fashion and anime industry, music videos of the 80s and Kurosawa’s “Dreams”.

As a final result of his bold experimentation we get a silly, cheeky, eccentric and pompous fairy tale in the form of a filmic play interrupted by tap dance and avant-garde performances! Wry humor, positive energy and sudden cuts are married to brilliant visual compositions that occasionally look like ukyo-e brought to life. The kaleidoscopic mise en scène is enveloped in the sounds of J-folk, jazz, classic, funk, calypso, glam-rock, hip-hop and sugared ballads to a great effect.