“You know the story of the crazy man who was fishing in his bathtub. A doctor with ideas as to psychiatric treatments asked him ‘if they were biting,’ to which he received the harsh reply: ‘Of course not, you fool, since this is a bathtub’…In [this story] it can be grasped quite clearly to what degree the absurd effect is linked to an excess of logic. Kafka’s world is in truth an indescribable universe in which man allows himself the tormenting luxury of fishing in bathtub, knowing that nothing will come of it.”

– Albert Camus, Hope and the Absurd in the Work of Franz Kafka

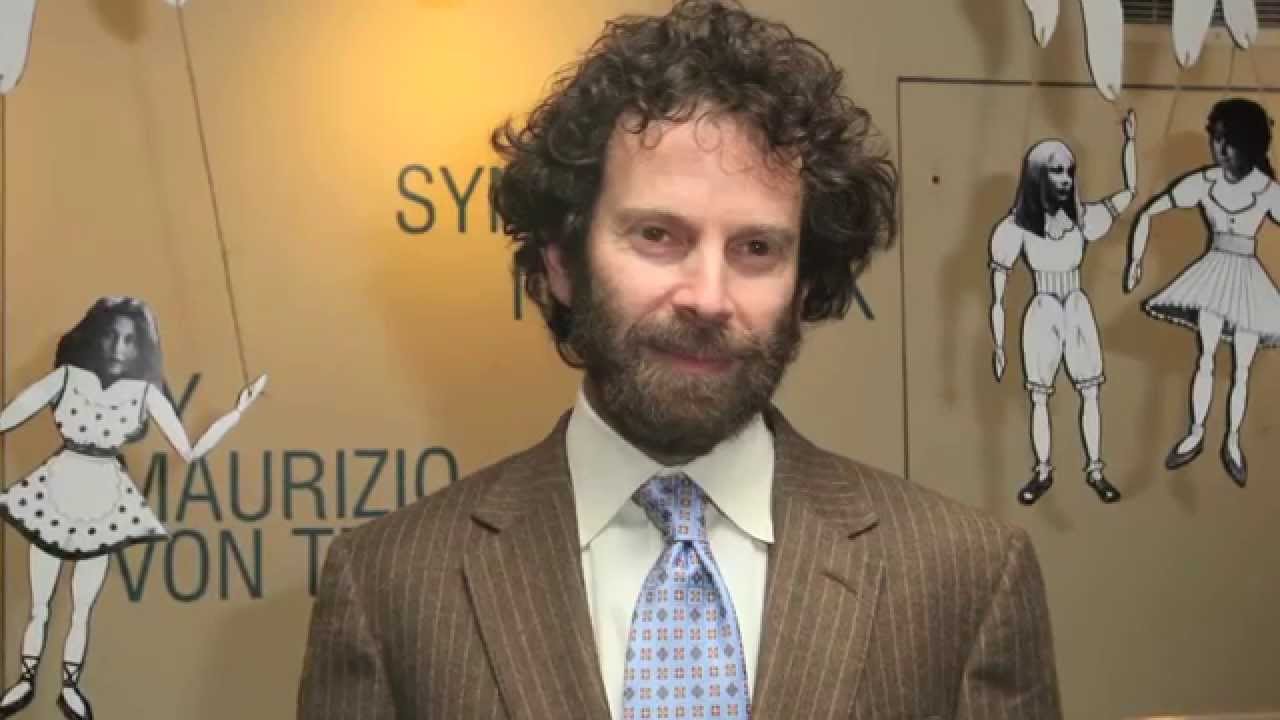

Charlie Kaufman’s world is also chock-full of the “tormenting luxury” of hope, knowing that nothing will come of it. “Surreal” may not be the best moniker to describe Kaufman’s films. Quirky, odd, imaginative, original, obscure, ponderous, ambivalent, melancholic, and confusing are also apt. Adjectives abound. If Woody Allen and Franz Kafka had a love child, that child would be Charlie Kaufman.

Few, if any, screenwriters have gained prominence in recent cinema. And those that have usually also directed their films. With the exception of Synecdoche, New York, which Roger Ebert called “the film of the decade,” Kaufman is content to let select others bring his vision to fruition.

The Woody Allen heritage of Kaufman is that he is not ashamed to poke fun at, or even harvest, his neuroses. Adaptation is a case-study in such. Kaufman’s humor, and there’s a lot of it, is admittedly darker and subtler than Allen’s.

Synecdoche, New York is clear example – à la Woody Allen – of how a creative person thinks that art may provide answers to life’s big questions, or at least be able to least quell his inner demons. Nor does Kaufman hold back in sharing his hopes and fears, in spite of the fact that his (or his characters’) fears are frequently realized and their dreams are dashed.

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, for instance, opens with Chuck Barris standing naked in front of a television broadcast of Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, his voiceover stating: “When you’re young your potential is infinite…You might be Einstein. You might DiMaggio. Then you reach an age where what you might be gives way to what you have been. You weren’t Einstein. You weren’t DiMaggio. You weren’t anything. That’s a bad moment.” Wasting your life is a fear that comes up over and over again in Kaufman’s films.

Speaking of dreams, the dreamlike quality of his movies, with their absurd logic, owes much of its heritage to Kafka, whom Kaufman has cited as one of his main influences. Guilt is rooted in fear, and Kaufman and Kafka have enough neurotic guilt between them to keep Freud busy for an eternity.

Kaufman’s films also bear elements of the avant-garde playwright Bertolt Brecht, particularly his “alienation effect,” with whom I’m sure Kaufman is not unfamiliar.

Besides Hazel (Samantha Morton) reading Kafka’s The Trial in Synecdoche, New York, perhaps the most straightforward “Kafkaesque” scenario in Kaufman’s films is in Anomalisa. Michael is summoned early in the morning by the hotel manager to his large but largely empty basement office after Michael’s night, or more like moment, of passion.

A mysterious authority figure calls Michael to a mysterious place, with a mysterious staff, all of whom know intimate details about his life, including the night before. And all of whom turn out to be in love with him, bluntly offering him carnal favors. It is classic Kafka.

What’s more, absurd as their situation may be, Kafka’s typically nameless characters keep pressing forward, though they are not really moving toward anything. Sometimes they do so in order to make sense of their situation; sometimes they do so for no reason at all. They seem to be motivated by some vague hope, even if they are constantly spinning their wheels.

Kafka’s stories hardly ever end. He simply never finishes writing them. They’re really not even stories. These aspects of the absurd figure prominently in many of Kaufman’s films.

“Dreamlike” does not mean ethereal, soft-focus cinematography. It means that Kaufman’s absurd logic is, similar to Kaka, literally like a dream. The succession of images are emotionally eloquent hallucinations, with their standard distortion, disorientation, and displacement.

Film as a medium is uniquely equipped for conveying this dreamlike effect. McLuhan’s famous phrase “the medium is the message” seems particularly applicable to Kaufman’s absurd logic. The medium has inherent possibilities to alter perception, in that what is presented (the content) depends on how it is presented (its form).

We catch glimpses of Kaufman’s dreamlike absurd logic in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, directed by George Clooney. It is about gameshow host Chuck Barris’s late life pretensions, or dreams, of being an assassin for the CIA.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, directed by Mike Gondry, captures much of the grab-bag, distorted nature of memories, though at times it seems heavy-handed. Gondry also directed Human Nature, a hilarious satire on…humans and nature. A comedic version of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, it is more lighthearted and campy than Kaufman’s other films.

While Kaufman puts a unique spin on it, such as a psychologist trying to teach mice which fork is the salad fork, that humans are ruled by base instincts despite all our high-minded explanations for these lizard-brain urges isn’t exactly a new revelation.

In Spike Jonze, director of Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, Kaufman seems to have found his soulmate. Both these films beautifully portray aspects of Kafka and Brecht. Anomalisa is a stop-motion film featuring animated puppets. It may be Kaufman’s most disconcerting film yet. A haze of midlife malaise engulfs its main character, who can never seem to clear the fog despite his best efforts.

I like to think of Kaufman’s films as a “Gedankenexperiment,” a thought experiment. Used by Einstein, among many other physicists, there is usually no way thought experiments can actually be performed – like what would happen if you rode a beam light – but they can help us gain better insight into what is at issue. Schrodinger’s cat is perhaps the most famous thought experiment. Yet they can be performed in film, in a way.

Similar to a Gedankenexperiment, Kaufman explores an alternative reality in order to bring it to bear on our reality, on life as we ordinarily experience it. “Surreal” may, then, be the appropriate term since the “sur” part, borrowed from French, means “above,” “over,” or “in addition to” life as we experience it.

It is not a Matrix-like simulacra and simulation, hyperreal or more real than real, but rather a method of visual estrangement (alienation). A visual estrangement more akin to original (so-called) surrealist films, for example in the famous scene in Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou in which a razor blade slices an eyeball.

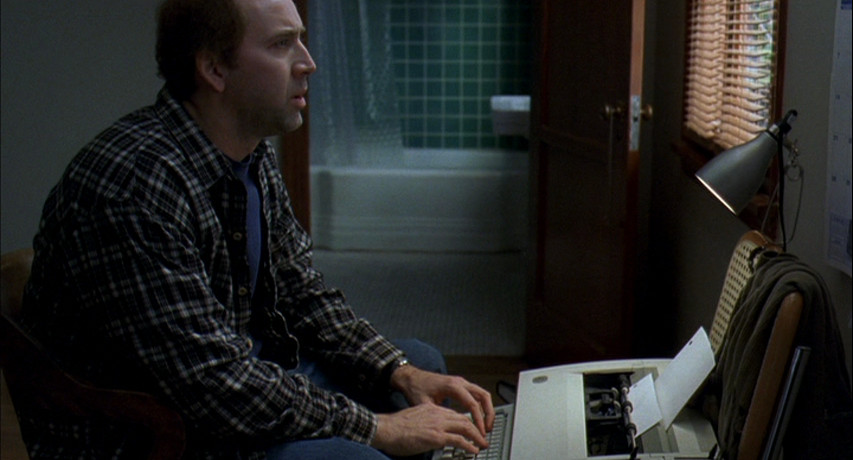

Much of what follows can be summed up in the following exchange from Adaptation, in which Kaufman, played by Nicolas Cage, is meeting with Valerie to discuss how to script a film about the book The Orchid Thief.

Kafuman: I want to let the movie exist rather than be artificially plot driven. I just don’t want to ruin it by making it a Hollywood thing, like an orchid heist movie or something. You know like changing the orchids into poppies and turning it into a movie about drug running. Why can’t there be a movie simply about flowers?

Valerie: I guess we thought that maybe Susan Orlean and Laroche could fall in love.

Kaufman: Okay. But…I’m saying… I don’t want to cram in sex or guns or car chases or, you know, characters learning profound life lessons or growing or coming to like each other or overcoming obstacles to succeed in the end. The book isn’t like that and life isn’t like that. You know, it just isn’t. I feel very strongly about this.

Kaufman, or rather his alter-ego identical twin brother Donald (who was also nominated for an Academy Award), proceeds to do exactly the opposite of what he feels very strongly about. Adaption has sex, guns, car chases, and characters learning profound life lessons – “you are what you love, not what loves you”; “Change is not a choice. Not for a species of plant, and not for me.” And, naturally, Laroche and Orlean fall in love.

Adaptation, in other words, is artificially plot driven, mostly toward the end, after Kaufman’s conversation with the teacher of the screenwriting seminar about finding an ending. Donald, who writes formulaic Hollywood scripts, has been attending these seminars.

Adaptation is thus a pun on adaptation of organisms, like an orchid, a book being adapted into a film, and how we as individuals adapt in our respective lives. Or how Kaufman adapted in order to save his ass in writing the screenplay.

Conflicted, solipsistic, darkly humorous, layered, self-referential, stories within stores within stories, characters physically inside other characters, melancholy, hope and failure. There are myriad entry points into Kaufman’s films.

Kaufman does appear tip his hand in nearly all his films, which I will note. Instead of covering each film individually, I’ve chosen some of his main, mostly overlapping, themes and how his films exemplify them. Guided by the logic of the absurd, though I will use that term a little promiscuously, my aim is to lay out a thematic template for his films, on top of which one might build certain interpretations.

1. The Self

Who am I? Or more precisely, is there an “I” at all? What if there is more than one “I” in our brains? What if there is no such thing as personal identity? If personal identity is neither personal nor an identity? Kaufman spends a lot of time inside his characters’ heads, oftentimes literally.

Confessions of Dangerous Mind; Joel’s (Jim Carey) memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind; a portal into John Malkovich’s head in Being John Malkovich.

Craig (John Cusack) explicitly says entering into the head of John Malkovich raises all of sorts questions about “the nature of self. The existence of a soul. Am I me? Is Malkovich Malkovich?” It is no coincidence that Being John Malkovich features puppets. Who or what is pulling the strings? Am “I” doing it? Recall that Anomalisa also features puppets being manipulated, although they don’t know they’re being manipulated.

Craig mentions that likes being a puppeteer because, as with being John Malkovich, he likes the idea of being inside someone else’s skin. Maxine will only be with Lotte, who thinks she is transsexual, when Lotte is inside John Malkovich; or with Craig after he learns to control Malkovich, pulling his strings to make Malkovich a famous puppeteer. At the end of the film, numerous old people crowd into Malkovich’s head to prevent themselves from dying.

In another case of multiple identities, as we’ve seen, Kaufman’s identical twin Donald from Adaptation was nominated for an Oscar for “Best Adapted Screenplay.” He presumably contributed to the Hollywood parts of the script which Kaufman initially didn’t want to write.

Chuck Barris in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind is also two people in one. Himself, and the version of himself that he rewrites into the past. Continuing farther into the hall of mirrors, Caden (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) in Synecdoche, New York hires an actor to play himself, who in turn hires an actor to play him, since that is what Caden did.

If one thing is evident in Kaufman’s film, it is this: we are strangers to ourselves. Human Nature emphasizes that we are nothing more than glorified apes. The references to Darwin in Adaptation are also not incidental. Your brain got here the same way everything did else, through evolution. Natural selection, the process of adaptation, doesn’t “care” if we understand our inner processes, insofar as an inability to do so does not negatively affect survival and reproduction.

Recent research in cognitive neuroscience has revealed that it is likely that a person does not have privileged access to her own mind any more than she has privileged access to the minds of others. Introspection and familiarity simply trick us into thinking that we do, since we think we have direct, first-person access to our own minds from the inside.

In fact, we may understand our own minds about as well as we understand the minds of others. Not very well. We make best guesses based on the clues we receive. Think of Chuck Barris’s show “The Newlywed Game” in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind. He says in the film that he premised the show on the idea that two people can’t possibly know each other as well as they claim they do. What made the show a success is that he was right.

Now apply this to your own mind. Our access to our own thoughts may be just as indirect and fallible as our access to the thoughts of other people. If our thoughts give the real meaning of our actions, our words, our lives, then we can’t ever be sure of what we say or do, or what we think or why we think it.

We can never be sure of the meaning of our thoughts and words because their original source is obscured and we lack access to it. Thoughts and words pop into our heads, though probably not randomly, from nonconscious regions of our mind much in the way that people pop into John Malkovich’s head. Something else is pulling the strings.

In addition to Being John Malkovich, Kaufman explores the nature of the self in other ways. In Eternal Sunshine a doctor targets and erases painful memories, usually ones of relationships gone sour. If, as it usually held, memory is the main basis of personal identity, by erasing memories one also erases oneself – however painful those memories may be.

It follows that pain and, more exactly, how you deal with it helps make you who you are. Pain individuates. Running away from it is “almost shameful,” as in this poignant exchange from Adaptation:

John Laroche: You know why I like plants?… Because they’re so mutable. Adaptation is a profound process. Means you figure out how to thrive in the world.

Susan Orlean: [pause] Yeah but it’s easier for plants. I mean they have no memory. They just move on to whatever’s next. With a person, though, adapting almost shameful. It’s like running away.

Adapting or erasing painful memories is almost shameful because it is like running away from yourself. Still, who or what is this “I” or “me.” In Synecdoche, New York Caden (who is a theatre director) tells his therapist (Hope Davis), a self-help guru, upon receiving funds for a MacArthur Grant that he “can finally put his real self into something.”

She responds by asking “what is your real self, do you think?…I guess you’ll have to discover your real self, right?”

Caden never discovers his real self, notwithstanding the actors he casts to play himself. Not for lack of trying. He puts forth a Herculean effort. His efforts turn out to be more Sisyphean, though.

He never finds his real self because there is not one; no “real” or “true” you, waiting to be discovered if only you employ the proper means. You are not special or unique. No one is. How can you be if you can’t understand that which purportedly makes you special – your own mind? Specialness aside, there are certain features we share with everyone.

At the end of Synecdoche, New York Caden is taking instructions from the actress playing him (Dianne West) through an earpiece, implying that his life was never authentically his own. The whole time he was, as explained above, working with what bubbled up from nonconscious regions of his mind. She is now that voice. Echoing the opening of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, she relays to him:

What was once before you – an exciting, mysterious future – is now behind you. Lived; understood; disappointing. You realize you are not special. You have struggled into existence, and are now slipping silently out of it.

This is everyone’s experience. Every single one. The specifics hardly matter. Everyone is everyone. So you are Adele, Hazel, Claire, Olive. You are Ellen. All her meager sadnesses are yours; all her loneliness; the gray, straw-like hair; her red raw hands. It’s yours. It is time for you to understand this.

The upshot is that Socrates’ classic dictum “know thyself” is a fool’s errand. One which we are nevertheless absurdly compelled to undertake. It is the price we pay for self-awareness. “Apes don’t even know they’re apes,” as pointed out in Human Nature. Or as Craig says to the chimp in Being John Malkovich: “You don’t how lucky you are being a monkey. I’ve got consciousness. It’s a terrible curse.” The price we pay for self-awareness is that we know we’re marionettes.

Perhaps, as suggested by the quote above, “get over yourself” is a better mantra. “You’ve never really looked at anyone other than yourself,” the actor playing Caden tells him in Synecdoche, York. “I didn’t jump, you idiot!” is Caden’s reaction after the same actor commits suicide by reenacting a moment in Caden’s life when he contemplated committing suicide while standing atop a ledge of a building.

Caden is so focused on himself that he fails to understand that he is just like everyone else – another obscure person in an obscure world. Look inside yourself and you should see, not your real self, but other people. You may not understand them, but they will implant pieces of themselves inside you. They are, as Craig averred in Being John Malkovich, “inside our skin.” They are internalized, incorporated, introjected.

Is this not also the logic of love? To “let someone in.” Contrary to directing a play or directing a random stranger how to walk down the street (which Caden actually does), to love is to open yourself up to something that is truly beyond your power to control, since there is no guarantee that your love will be returned. To love is to be vulnerable: by giving someone the power to destroy you and trusting them not to.

As opposed to an actor following a script and taking directions, the beloved has her own will, and she can always say ‘I love you not.’ Maybe the life lesson from Adaptation is profound after all: “You are what you love, not what loves you.” Caden, a self-obsessed neurotic, is ignorant of this possibility. His is an ignorance without the bliss.

In sum, Kaufman’s films intimate that personal identity is neither personal nor a singular identity. It is a multiplicity of people, shown in the multitudinous examples above, who have touched your life in some way. Whatever the psychodynamics of the self may be, “I” – that which is distinctively me– am merely another neural circuit in a human brain.

The rest of “me” is shared with others, in my brain(s) and theirs. (N.B. For what it’s worth, Freud held a very similar position: the ego is comprised of precipitates of abandoned object cathexes. “Object cathexes” means people in whom you had an emotional investment)