4. The Nature and Function of Art

A great deal of art can be seen as expression of the life and values of the community. Kaufman’s films are more, shall we say, Freudian, focusing on inner conflicts of the individual. The existential “tormenting luxury of hope” doesn’t seem very relevant to hope for food, clean drinking water, or medicine for preventable diseases.

Whether his inner obsessions amount to “white people problems,” a form of bourgeois intellectual masturbation, remains to be seen. Kaufman nonetheless acutely senses both the value of art and how it can mislead us.

Regarding the latter, Kaufman is suspicious of stories, as they are traditionally presented, going all the way back to Aristotle: As referenced in Adaptation:

Story = character(s) + conflict (predicament) + resolution

Even the false narrator format, typified by Fight Club, follows this formula. Nearly all stories do. Hazel in Synecdoche, New York flatly states the problem with stories.

The trouble, she says, is that “the end is built into the beginning.” There is a preconceived end, purpose, or intention to a story, and the story is an unfolding of such clockwork necessity. Yet life, both in general and for individual human beings, has no original or preconceived purpose.

You weren’t meant to be or do this or that. Life is absurd, not in the sense that it is incomprehensible, but in that it is pointless and purposeless. Unlike a story, in which each aspect rushes headlong to an ending where everything falls into place, as it is meant to.

Newton kicked purposes out of physics in the 17th Century, and nothing in subsequent centuries gainsaid him on this score. Darwin followed suit by ejecting purposes from biological life in the 19th Century, proving that natural selection lacked foresight.

Natural selection is blind to the future. Richard Dawkins observes: “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.”

Since there are no purposes in nature, and since the universe which spawned us is indifferent to human aspirations, you can’t give your life meaning or purpose, because you can’t give your life something that does not exist. That, coupled with the inscrutability of meaning addressed above, is the general basis of the absurd.

This is not say that life is completely random and lacks order. Just like rest of nature, we follow patterns, rather predictable ones. The truth, as usual, at least for life as we experience it (for human reality) is somewhere in between – somewhere between clockwork and chaos.

Yes, we have our patterns. But contingency, chance events, can strike us down from nowhere at any time. Albert Camus laid out his notion of the absurd in 1942 in The Myth of Sisyphus. He is alleged to have said that dying in a car accident is the most absurd of all deaths. 18 years later he died in a car accident.

In the same vein, Kaufman’s logic of the absurd is never more evident than in the stirring scene in Adaption when Laroche is pulling out of his driveway with his family in the car. His view of the road is obstructed, and he is not paying much attention. They are blindsided by an oncoming car, killing his mother and uncle. The accident left his wife in coma, who divorced him after she regained consciousness. A month later hurricane Andrew wiped out his nursery.

It’s a knotty problem. On one hand, we crave meaning, coherence, purpose, and stories give them to us. On the other hand, life is absurd and has no meaning or purpose. One cannot help but think of Nietzsche’s quip that “we have art in order not to die of the truth.” Jonathon Gottschall sums it up nicely in his book The Storytelling Animal.

The following passage could equally describe the film Adaptation, and to lesser degree Chuck Barris in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind manufacturing lies about his past. It also relates to Malkovich/Craigs’s tongue-in-cheek comment that “art tells the truth, even when it lies.” Stories lie. But in so doing they reveal truths about our deeper fears and desires.

The storytelling mind is allergic to uncertainty, randomness, and coincidence. It is addicted to meaning. If the storytelling mind cannot find meaningful patterns in the world it will try to impose them. In short, the storytelling mind is a factory that turns out true stories when it can [‘a film simply about flowers’], but will manufacture lies when it can’t [Donald’s Hollywood contributions].

Narratives (stories) bind contingency. They give it order, meaning, a place in the scheme of things. Kaufman’s reply is: not so fast. The accident which killed Laroche’s family and left his wife in a coma, for which he might be more than partially responsible, wasn’t exactly written in the stars. It doesn’t mean anything. It was a chance-event, a trauma that will forever be rattling around his brain; his brain unable to put it in place, as a story does.

Traditional narratives are also driven by want, desire, and goal-motivation, as mentioned in Adaptation. Below is an excerpt from a 1913 guidebook for screenwriters. It is as true today as it was then.

It should be remembered that ‘want,’ whether it be the wanting of the love of a woman, of a man, of power, of money or food, is the steam of the dramatic engine. The fight to satisfy this ‘want’ is the movement of the engine through the play. The denouement is the satisfaction or deprivation of this desire which must be in the nature of dramatic and artistic justice.6

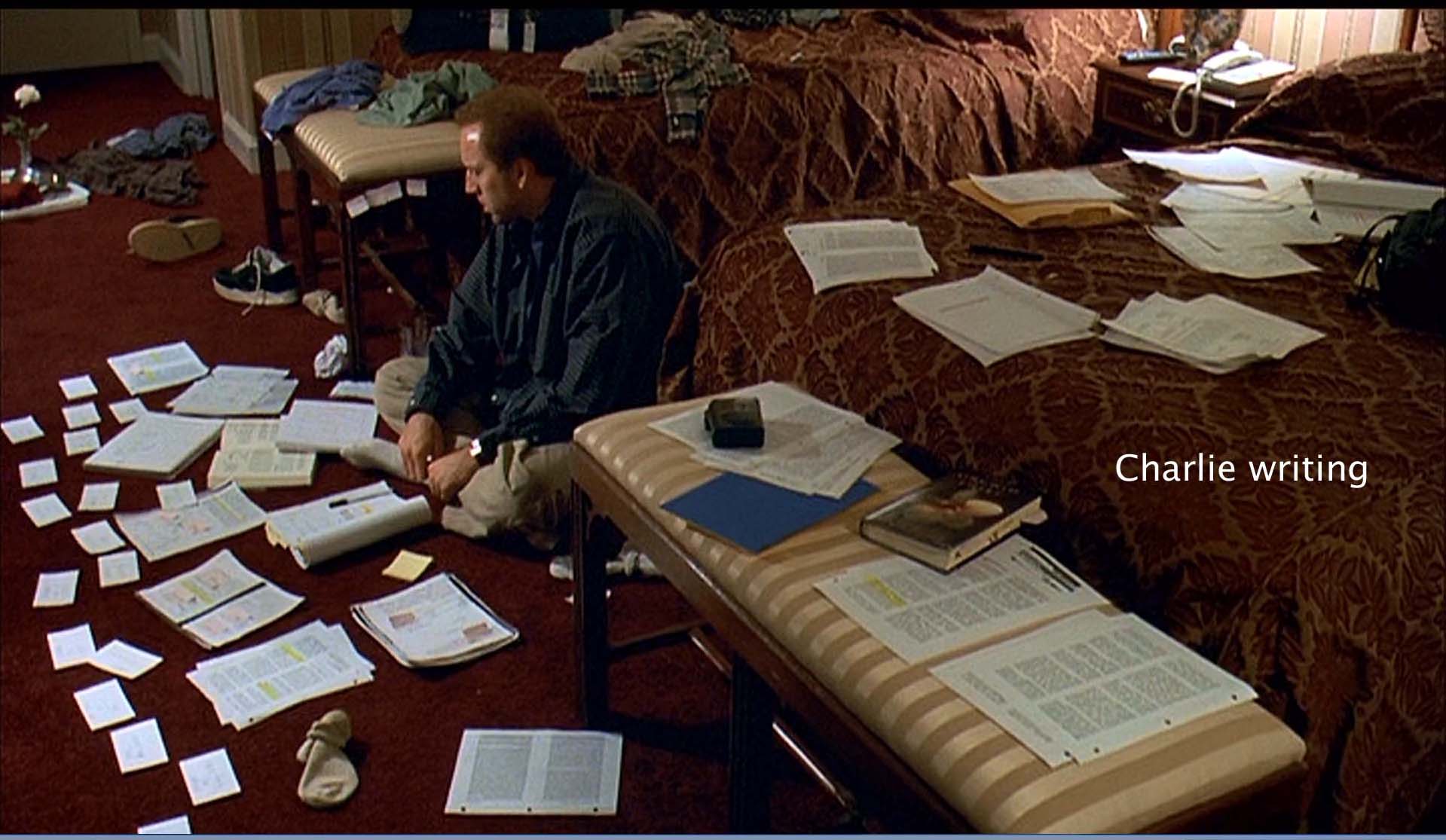

Kaufman’s films, for the most part, exhibit nothing of the kind. His characters seem to be drifting, searching, stymied by this or that. They don’t make things happen so much as things happen to them. Kaufman asks the teacher of the screenwriting seminar in Adaptation: “What if the writer is attempting to write a story where nothing much happens? Where people don’t change. They don’t have any epiphanies. They struggle and are frustrated. Nothing is resolved. More a reflection of the real world.”

For Kaufman, one function of art is that it is a way of sorting things out, of making sense of life. “I need to make sense of it!,” exclaims the now civilized (or conscious) Puff the ape-man after he has returned to the woods at the end of Human Nature. And in Synecdoche, New York: “He [Caden] strived valiantly to make sense of his situation,” his life. It seems that for Kaufman to express thoughts and feelings in art is part of understanding them.

Art, then, is a way of coming to terms with the harsh, unpleasant realities of life by developing an acceptance of self and (an absurd) world without falling into despair and without taking recourse to comforting illusions, such as religion, pop psychology, or romanticizing through stories or other means.

In what could be especially applicable to Laroche from Adaptation, Glen Duncan writes: “The first horror is that there is horror. The second is that you accommodate it.”7 Accommodate it. Accept it.

5. Acceptance

Acceptance isn’t a typical plot resolution, tying up loose ends in a neat little bow. Nothing is resolved in acceptance. Closure is a comforting illusion. Nothing is ever over. There is no justice in the end, artistic or otherwise. Forget fairness, too. You can do everything right and still get screwed. And as both Human Nature and Synecdoche, New York suggest: you can never go home again, because there is no home to go home to.

Many or most of Kaufman’s characters struggle to move forward because they are haunted by the past, as if they lost something they never really had. Kaufman hints that something similar to this is what motivates Chuck Barris’ claims in his memoirs that he was an assassin for the CIA in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind. Barris thinks he has lost the future he once had. He cannot move forward because at his age there is nowhere to go. So he goes backwards in an attempt to recapture his future.

Acceptance is a way of moving forward. Acceptance means you learn to live with it, whatever “it” may be. Or to die with it, in the case of Synecdoche, New York. Acceptance is the final stage of mourning, also a loss. Acceptance is adaptation, as in Adaptation; shameful as it may be.

The philosopher Jagger once said: “Childhood living is easy to do.” Stories are for children, because in the hands of adults they are deadly. The greatest story ever told, itself a refusal to accept absurdity, launched an untold amount of violence, suffering, and death. It is a trite to say that accepting struggle and frustration, accepting our finitude, is the nature of the beast. But that doesn’t make it any less true.

Perhaps Kaufman’s most vivid illustration of acceptance is the end of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Joel and Clementine had just met again for the first time after having their memories of each other erased. A rogue employee has mailed them the tapes which recorded why they wanted their memories erased. They are filled with typical complaints after the burst of passion has worn off and you spend too much time with someone.

I hate her hair; I hate his condescending smirk; I hate the way he squeezes toothpaste out of the tube. The tapes are playing in the background as Clementine and Joel are confused as to whether they should embark on this journey again. She tells him that he will eventually get tired of her. That she will get on his nerves and he on hers. Etc. Joel responds with two words: “That’s okay.” With that the movie ends.

The main point, again, of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind is that Chuck Barris could not accept his life as he had lived it, or properly mourn the loss of his future. So in his memoirs he dreamed up stories of being an assassin for the CIA, weaving them into accounts of his past.

At the end of Synecdoche, New York Caden seems to realize and accept that his life has been a complex network of dependency, and this entails being vulnerable. He rests his head on the shoulder of a stranger, intoning “I know how to do this play now.” Immediately after which instructions come through his earpiece: “die.” He does.

Perhaps the voiceover at the end of Adaptation says it all. After telling Amelia that he has finished the script and is eager to move forward Kaufman writes/narrates: “Kaufman drives off from his encounter with Amelia filled for the first time with hope.”

Humans didn’t evolve to be happy. We evolved to pursue happiness. Even it means fishing in a bathtub. Kafuman’s films teach us that, absurd as it may be, hoping while knowing that nothing may come of it is neither pessimistic nor futile. Far from it, it is an act of courage. It takes courage to face life on its own terms, to accept it, and to move forward.

References

1. Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. (1955). New York: Vintage Books.

2. Rosenberg, Alex. (2016). “Why You Don’t Know Your Own Mind.” The New York Times, July 18. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/18/opinion/why-you-dont-know-your-own- mind.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&_r=1

3. Freeland, Cynthia. (2001). Art Theory: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, p.121.

4. Dawkins, Richard. (1995). River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life. New York: Basic Books, p.133.

5. Gottschall, Jonathon. (2012). The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human. New York: First Mariner Books, p.103.

6. Bordwell, D., Staiger, D., & Thompson, K. (1985). The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. New York: Columbia University Press, p.160.

7. Duncan, Glen. (2012). The Last Werewolf. London: Vintage Books.

Author Bio: Scott Borchers has published a book, Hegel’s Science of Logic and Global Change: A Philosophical Explanation of an Environmental Crisis, as well as several articles on philosophical psychology. He lives with his cat in Nashville, TN. You can find him on Facebook or Scott.Borchers@mtsu.edu.