Over the last 15 years, director Martin Scorsese has become the ultimate cinematic success story. Films such as Gangs of New York, The Departed, Hugo and The Wolf of Wall Street have been successful with both audiences and critics alike, garnering good reviews while pulling in big box office bucks. But it wasn’t always such smooth sailing for the director who emerged from New York University in the mid 1960’s and burst on the scene during the heyday of the ‘New Hollywood’ era.

Scorsese sometimes struggled to find an audience for his films, particularly during the 1980’s and 90’s, while critics were sometimes quite harsh to his efforts to expand his stylistic range.

Here then are 10 films that were, in some ways, overlooked or underrated on their original release that should now be reconsidered in light of the fact that Martin Scorsese is regarded as one of today’s greatest cinematic masters. While all these films fall short in some way, they are all definitely worth seeing if you get a chance.

1. Mean Streets (1973)

After emerging from film school, Scorsese found work on his own documentaries and on on films such as Woodstock (1970), as well as work for low budget master Roger Corman. His first studio feature was Mean Streets, released in the fall of 1973.

The film failed miserably at the box office, however, putting the career of the young director in jeopardy despite some critical praise for the movie.

Mean Streets centers around the character of Charlie (Harvey Keitel), a small time hood working for his uncle Giovanni (Cesare Danova) on the streets of New York’s Little Italy, the neighborhood from which Scorsese himself hailed.

Charlie is secretly seeing Teresa (Amy Robinson), a girl his uncle disapproves of, while he also tries to protect Johnny Boy (Robert DeNiro), Teresa’s sometimes psychotic cousin.

Mean Streets sets forth Scorsese’s primary thematic preoccupations very plainly: the struggle between the impulse towards good and evil, the conflict between the saintly Catholic church of his upbringing and the mean streets on which his characters must survive, and the sometimes confusing sexual urges that undermine his characters’ resolve.

Although it was largely considered a failure on its first release, the film quickly developed a cult reputation and is now viewed as an important early work from one of the cinema’s greatest practitioners.

2. New York, New York (1977)

After Mean Streets, Scorsese was picked by star Ellen Burstyn to helm Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, a woman’s film that was an unusual project for him, which was a success on its release in late 1974. This was followed by Taxi Driver (1976), an enormous success with both critics and filmgoers alike, which is now regarded as one of the greatest films of all time.

Fresh off these successes, he chose a most unusual project: New York, New York, a musical starring regular collaborator Robert Di Nero and Hollywood royalty, singer Liza Minnelli.

New York, New York is the story of the tempestuous relationship between saxophone player Jimmy Doyle (De Niro) and singer Francine Evans (Minnelli). They meet on V-J day in New York and end up going to an audition together, where they are paired by a club owner as a boy-girl act and become a huge success. Falling in love, the two have a child together, but Doyle’s hot tempered nature puts an end to the relationship and soon he and Francine go their separate ways.

In the end, Francine’s lyrics to Doyle’s song “New York, New York” becomes a major hit, but the two star crossed lovers are unable to reconcile their professional success with their personal lives.

New York, New York was Scorsese’s first big budget film, and it was given a major promotional buildup. The film’s box office failure and the critical drubbing that followed hurt the young director badly, and Scorsese realized that his willingness to expand himself stylistically could be a major drawback in the eye’s of some critics.

Despite this, he carried on, and in hindsight New York, New York can now be seen as an interesting variation on some of the director’s familiar themes.

3. The Last Waltz (1978)

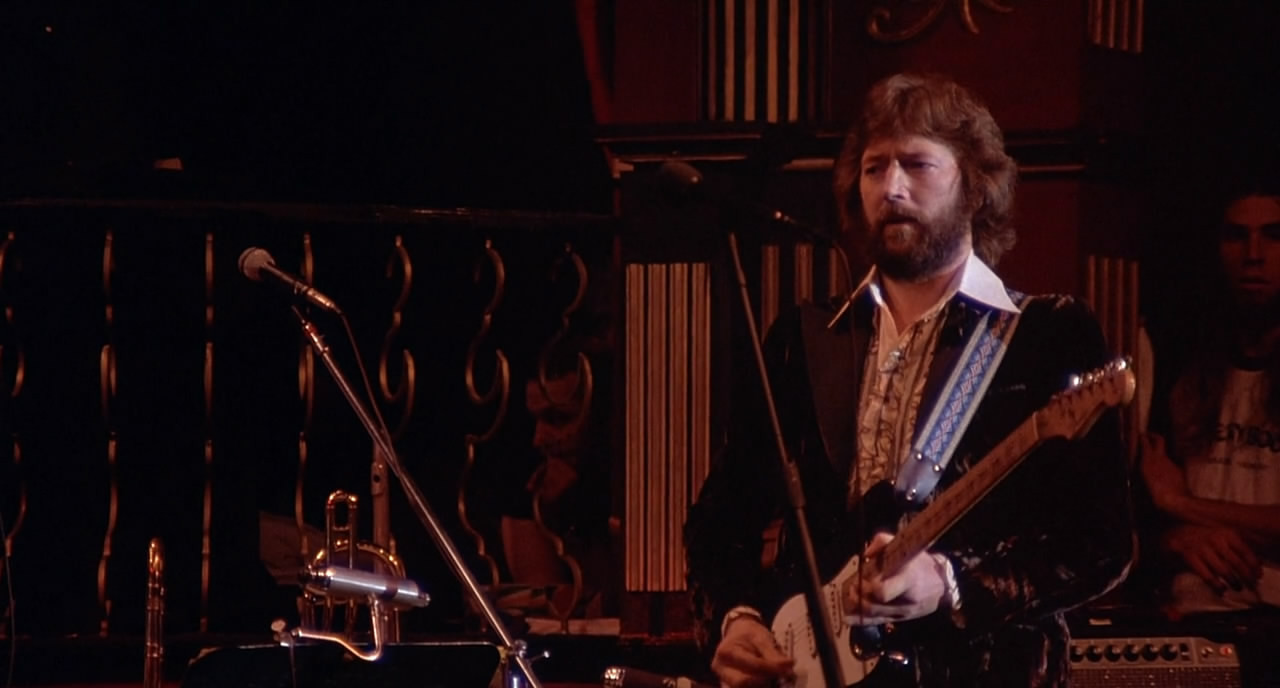

Scorsese is hardly a documentary filmmaker, but he has dabbled in documentaries from time to time with a mix of success. In 1976, guitarist Robbie Robertson of The Band, a group Scorsese had long admired, asked the director to film the group’s final performance at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, and the resulting film is now regarded as one of the greatest rock concert films of all time.

Deciding that the highest quality images were required for this landmark event, Scorsese dispensed with the lightweight 16mm cameras that had previously been used in such films as Woodstock and Gimme Shelter (both 1970), using larger 35mm cameras to record the concert.

Although some technical problems were encountered by the director and his crew, the end result was beautiful footage of some of the greatest rock acts of the era performing live with The Band in their final concert together. Scorsese added interview footage and a few soundstage songs to the film, which was released in 1978.

Although critics and audiences generally hailed the film, some have criticized The Last Waltz for focusing too much on guitarist and songwriter Robbie Robertson, who befriended Scorsese and later worked on several of his films. Still, The Last Waltz remains a great testimony to both the music of The Band and to the man who made the movie.

4. The King of Comedy (1983)

The 1980’s were Scorsese’s most difficult period, as his films often performed poorly at the box office and reviews were often critical. Raging Bull (1980), now regarded as a masterpiece, did only marginally well financially and was given mixed marks by critics, many of whom abhorred the film’s violence.

Scorsese’s next film, The King of Comedy, a scathing look at the influence of television and fame, fared even worse than Raging Bull, failing at the box office while critics took their pot shots at the film’s dark humor and offbeat story.

Robert De Niro is Rupert Pupkin, an obsessed fan of nighttime TV host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis). Pupkin idolizes Langford, doing everything he can to get the TV host’s attention while trying to become a successful comedian himself. Eventually, Rupert joins up with another Langford stalker, Masha (Sandra Bernhard) and they embark on a crazy scheme to kidnap the TV host and take over his show, giving Rupert his chance of a lifetime to become famous.

In an ending somewhat reminiscent of Taxi Driver, it appears that Rupert’s scheme has actually worked and he has finally achieved the fame that he so desires, despite ending up in jail for his efforts.

With the shooting death of John Lennon in 1980 and John Hinkley’s unsuccessful attempt to assassinate President Reagan the next year, it’s not surprising that Scorsese seized upon this story as a timely commentary on our fame obsessed society. On its release, the audiences of the 1980’s (used to more standard fare) were confused by the movie, while critics were brutally unfair in their assessment of this unique film.

In the intervening years, however, the reputation of The King of Comedy has grown substantially, and it is now rightly regarded as one of the director’s major works and an insightful take on the difficulty that fame and celebrity pose in our society.

5. After Hours (1985)

Retreating from his big budget failures and the collapse of his personal project The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese next made a small scale New York based black comedy called After Hours in 1985.

Starring Griffin Dunne as Paul, a word processor who heads down to New York’s SoHo district after a chance meeting with Marcy (Rosanna Arquette). On his way to Marcy’s apartment in a cab, Paul loses his money when a $20 bill he was carrying flies out the window.

This begins a series of nightmarish misadventures in which Paul spends the night trying to get out of SoHo and back home. He is eventually mistakenly identified as a home burglar and chased by an unruly mob before he is finally encased in plaster by a deranged sculptress and deposited back in front of his office in the early hours of the next morning.

After Hours was actually modestly successful at the box office and was given decent to good reviews by the critics who had savaged his recent work. Compared to Scorsese’s previous efforts, however, After Hours seemed a very modest film at the time, almost a return to the director’s New York based roots.

After Hours has also seen its reputation grow in recent years and while it will never rank with Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, it is now regarded as a significant entry in Scorsese’s body of work. The darkly black comic tone of the film, somewhat unusual for the director, occurs again from time to time in later films such as Goodfellas and Bringing Out the Dead.