The New Hollywood boom of the 1970s was full of undisputed landmarks, undeniable masterpieces which we all look back on with reverence. But one cannot deny that there are far more buried gems than lauded classics from that rich and varied period in filmmaking history. Indeed, for every Godfather there are dozens of unsung gems hidden away in the annals of time. Though one might get frustrated that the movies we love don’t get their due credit, there is much joy to be had in digging deep into that era and finding the gold beneath the thick layers of dust.

It would be easy for most film buffs to list a thousand overlooked American films from the 1970s. To start with then, here are ten notable omissions. from the officially recognised classic category.

1. A Safe Place (1971)

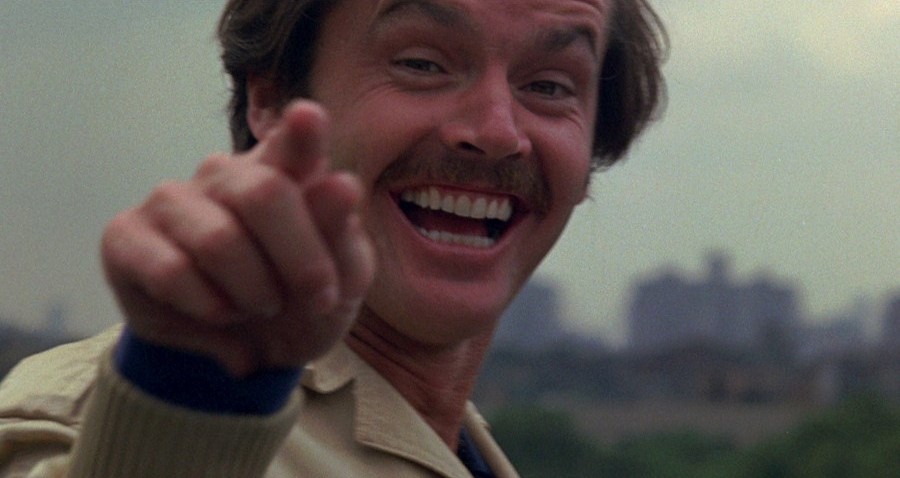

Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place follows Noah (Tuesday Weld), a young woman living alone in New York who looks back to her childhood, “her safe place” from long ago. She has flashbacks to an enigmatic street magician she met as a child, played by a wonderful Orson Welles, while getting through two relationships, one of which is with the modern and hip Mitch, played nicely by Jack Nicholson.

The film is a moody and imaginative trip inside Noah/Susan’s head and is crammed full of marvellous imagery. Apparently put together from 50 hours of footage, Jaglom’s film is pure and full of soul. His central character is an isolated flower child, but the film works effectively away from its early 1970s framework. Indeed, there is no way anyone could place this among the more dated films of the late sixties and early seventies because it seems, thanks to Jaglom’s vision, completely of its own time.

Weld is superb in the film, in what might be her most free and liberated performance. Giving her room to breathe and express herself, Jaglom made way for a truly stunning effort. In a way, what Weld does in this film is not a performance or display of “acting”, but a kind of being. She is child-like but also a woman in every way, and Jaglom gifts her the room to be playful and inventive. Though Weld holds the film together in some ways, Orson Welles has the showier, more charismatic part. He is tremendous in fact, and for me it exists as one of the finest bits of acting he did for another director. For Jaglom, it was a dream to direct Welles, a man he had always admired and very much wanted for his own debut feature.

A Safe Place was regarded as a key feminist movie upon release, and though it did next to no box office, it has since garnered a cult following, like much of Jaglom’s work. I view it as a free, liberated, exciting bit of introspective cinema, an experiment few if any filmmakers would dare to make these days. “It’s a film about the loss of innocence,” Jaglom later said. “About how dwelling on the seemingly beautiful past is really a killer and stops you from being able to live in the present and function for the future.” A message we can all learn from I believe.

2. Alex in Wonderland (1970)

A film that too often gets completely ignored is Paul Mazursky’s flawed but extremely interesting, Alex in Wonderland (1970), a self-referential, Fellini-esque take on the life of a filmmaker and his daily struggles. In the lead role of Alex, Donald Sutherland – newly famous thanks to roles in such landmark films as MASH and Kelly’s Heroes – gives a controlled, reliable effort, and even though he is playing the artistically insecure type, his presence does provide the film with a certain grounded quality it requires, especially given there is no plot holding it together. But the whole thing is a lot of fun; Mazursky’s playful direction keeps things entertaining, and Sutherland is engaging throughout.

It also features a highly memorable cameo from Fellini himself, only a few years before he would cast Sutherland in his version of Casanova. Sutherland later said he was just plain wrong for the part of Alex, and also confessed that he had turned down the lead in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs in order to work with Mazursky. (Sutherland as the mathematician turned primal male in Straw Dogs is one of the great what-ifs in cinema history.)

Like Henry Jaglom, Mazursky is an important voice from the New Hollywood boom but one who too often gets overlooked completely. This gem is well worth the time of any fan of character-focused American cinema.

3. I Never Sang for My Father (1970)

Gene Hackman received his second Oscar nomination for his part in I Never Sang For My Father (1970), a role that changed his career for the better. Directed by Gilbert Cates, it was written by Gilbert Cales who adapted it from his own hit play. In the picture, Hackman plays college professor Gene Garrison, a widow who lives in the shadow of his domineering father, Tom, played by Melvyn Douglas.

The film begins with Gene “enjoying” a night with his parents, and the constant jibes from his dad replaying in his mind as he returns home. When the mother is hospitalized with a heart attack, and dies soon after, Gene finds himself spending more time with his dad, resulting in much tension and discomfort. At the same time, Gene’s girlfriend Peggy actually warms to old Tom, all the while Gene is hatching a plan to get remarried and leave his old man behind for a new life. This leads to crippling inner conflicts for the younger man.

I Never Sang For My Father, as with other pictures about inner conflicts from this era, is not a film one can get a genuine idea of from the plot outline alone. Like the same year’s Five Easy Pieces, another melancholic drama dealing with father issues, the gold is in the performances, the interactions between the main characters, and the tension in the air. It is Hackman who makes the film what it is, giving a subtle, multi layered effort where he says more in gestures and silences than in any choice of words. The love for his father is there underneath the surface; it’s just getting it out there and expressing the emotion which is the challenge. Yet it’s a challenge Hackman as an actor is willing to take, and he tackles it beautifully with grace.

I Never Sang For My Father is undoubtedly all but forgotten and is probably only known by Hackman die-hards. It deserves a proper re-release, and a re-appraisal for that matter.

4. Prime Cut (1972)

After his glorious moment at the Oscars, winning Best Actor for The French Connection, Gene Hackman continued to work solidly. Some of the films were major blockbusters (Poseidon Adventure), others more arty fare. Prime Cut (1972) is sadly one of the less talked-about films he made in the early to mid 1970s. Directed by Michael Ritchie, it follows Lee Marvin as Nick, an enforcer sent from Chicago by the mob to retrieve a debt of £500,000 from Kansas City meat industry tycoon “Mary Ann”, played with menace by Hackman. But this is no straight forward gangster shoot ’em up.

There are hints of homosexuality between Mary Ann and his twisted brother, and more disturbingly there is a sub plot where Nick saves a young girl (played by Sissy Spacek) from Mary Ann’s human sex slave sale, where the teens are drugged and taken away by the highest bidder. On top of this is the fact that, at the film’s very start, it’s clear that Mary Ann has arranged for one of the Chicago mob’s men to be mashed up and processed into sausage meat.

All this, it’s fair to say, made the picture pretty controversial in 1972. It may leave a bit of a nasty taste in the mouth, but it’s bold, brilliantly acted and finely constructed. It’s so well written in fact that it literally flies by, and it’s peppered with quotable dialogue. There is a statement being made here about meat as a concept, as dead flesh, the price of flesh, and the value of human beings when compared to our more primitive friends who are bought, sold and processed. But for the most part it’s just an exciting, utterly involving thriller. Marvin is the solid hero, while Hackman is pure sleaze as Mary Ann, a creep who runs his empire with ruthless abandon, unconcerned with the world outside his realm of seediness.

5. The Dion Brothers (1974)

One long-buried gem whose obscurity seems particularly unfair is The Dion Brothers, also known as The Gravy Train. Directed by Jack Starrett and co-written by Terence Malick under the name David Whitney, the picture is almost ludicrously entertaining from start to finish.

It follows the Dions, Calvin and Rut, played by Stacy Keach and Frederic Forrest, in their misadventures as criminals across America. Early in the picture, the two ex-coal miners pack their jobs in and agree to help out in an armed robbery that initially goes well but turns out to have been set up so the Dions will take the fall while the organisers, Tony (Barry Primus) and Carlo (Richard Romanus), get away. But the Dions are sharper than they are given credit. Escaping a police ambush disguised as cops, they head out on the road for revenge, swearing to track down the weasel who left them for dead.

First off, the script is plain hilarious, littered with little nuggets of urban wit and end-of-your-seat scenarios. The acting is terrific too; Keach is the cool, moustached older brother, a smooth con man who has his wits about him; Forrest is the fool hardy pup with a short fuse and a willingness to go extreme pretty quickly. The chemistry between the pair carries the film along nicely, and it’s surprising that in no time at all, as much as you are enjoying proceedings, the film zooms by in a flash.

The film was all but ignored upon release, but thankfully has developed a bit of a cult following as the years have gone by, with one fan being Quentin Tarantino, who at one point even wanted to remake the picture. Even Guillermo Del Toro loves it, having once being quoted as saying: “Every person on the fucking planet should see this movie, it’s a classic!”

Sadly, despite its cult film credentials, it still hasn’t had an official physical release yet. Hopefully one day it will get a proper Blu-ray release with all the trimmings.