6. Shampoo (1975)

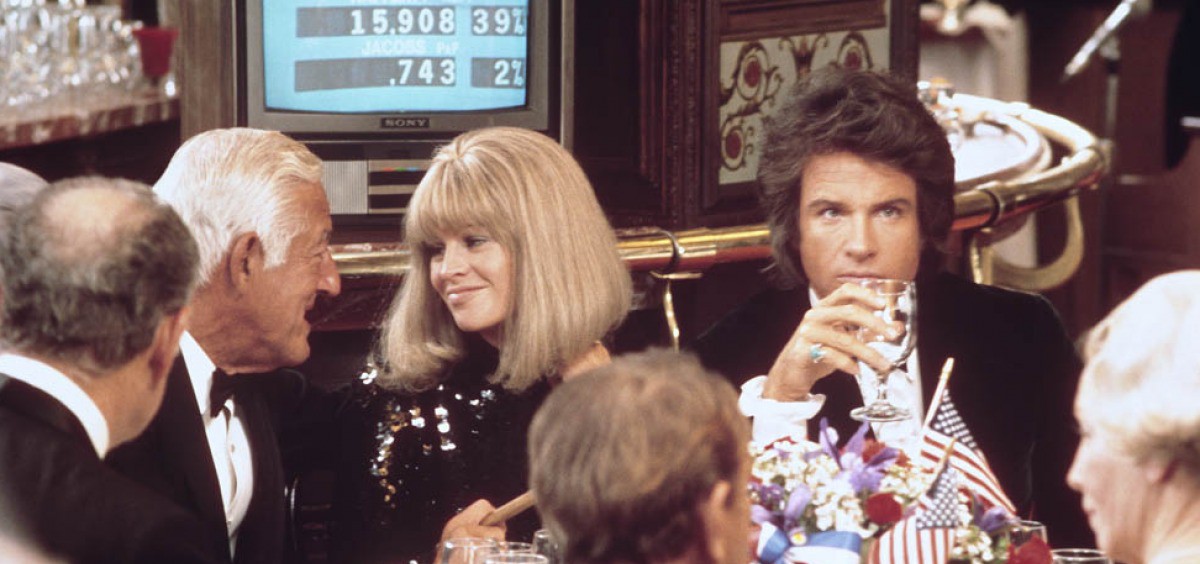

Out of all the prominent directors of the 1970s whose style is inseparable from their time and place, Hal Ashby is perhaps the most muted and soulful. His films gently examine the human spirit and the current cultural moment until his direction reveals itself to be biting. Not only was Shampoo the quintessential star vehicle for Warren Beatty, but it also brushes upon fame, sex, and politics in the most unassuming posture.

Shampoo centers around Election Day 1968 in Beverly Hills, where a promiscuous hairdresser, George Roundry (Beatty), juggles personal and professional affairs throughout the day. The backdrop of the impending Richard Nixon presidency lingers throughout the narrative but is never obtrusive in nature–a quality attribute of Ashby. Like all the best ‘70s character studies, the film is irresolute on the matters of how one person can improve the world around them. The election, as it pertains to real life, evokes simmering anxiety in society. While following from George’s perspective, Shampoo is Altmanesque in its documentary-like depiction of a breathing community.

Ashby engages in meta-commentary regarding Beatty’s stardom and well-known affinity towards uncommitted romance. The character’s reckoning with his grandiose lifestyle is the most nuanced acting Beatty has ever brought to the screen. The film expresses the clash of the actor’s counterculture and mainstream tendencies. A comedy in spirit, the film is not bending over backward to make the audience laugh. Instead, it flows on a particular wavelength that doesn’t mesh with everyone, but for those who are susceptible to Ashby’s vision, it can be transcendent. Shampoo is undefinable in the most curious ways, as Ashby’s film deals with grounded and accessible ideas but will still leave viewers wondering more.

7. Opening Night (1977)

A perennial voice of independent cinema, John Cassavetes was the antithesis of Hollywood and the general norms of filmmaking. The unmistakable visual aesthetic, humanist acting and authentic worldview of the director is overwhelming. Opening Night, Cassavetes’ follow-up to his standout films A Woman Under the Influence and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, certifies the director as a premiere indie voice before the attribute was seen as financially viable.

Opening Night follows a renowned actress Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) teetering on the edge of a breakdown in anticipation of a big Broadway opening as a result of her substance abuse and witnessing a fan being killed in a traffic accident. The film grapples with fame and the precarious nature of life as a celebrity in the least pretentious manner. Cassavetes’ familiar raw direction gives the film a necessary edge. Buried underneath the coarse characterization of Myrtle is a sympathetic portrayal of the lead, who is played by Cassavetes’ wife. The unpredictability of Myrtle synchronizes with the chaotic environment displayed in Opening Night.

Rowlands, per usual, knocks it out of the park with her deeply humane depiction of a star attempting to stand her ground and make right with the world. Under misguided hands, Myrtle could have devolved into a caricature. Out of everything in his filmography, Opening Night is the best example of Cassavetes’ combating formalism with realism, as he uses the former to reconcile with the traumas of the latter. This helps Opening Night lure the audience into the character’s desires, and how her relationship to her artificial world in the theater production manifests itself in reality.

8. Blue Collar (1978)

Already hot as the screenwriter of Taxi Driver, Paul Schrader emerged as a director with this cutting, cynical film about the perilous corporate ruling of working-class America. Blue Collar is Schrader at his most direct and grounded, in tribute to the class of people that finally received proper recognition from Hollywood.

Blue Collar tracks three auto workers (Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, and Yaphet Kotto) attempting to steal from the local union and discover rampant corruption to use as blackmail. All three performances are electric, but Pryor especially stands out, as his dramatic chops exhibit his all-around talents. The film is pure ‘70s cinema–showcasing the frustrated everyday folk working up the courage to undermine the greed of the wealthy class. Perhaps Schrader plays his hand too evidently in the film, but the characters’ demise is inevitable. Schrader’s iconography of corrupt unions as a treacherous system is quite resonant. The director’s wheelhouse is in perverse character dramas.

When Schrader pivots towards genre tendencies, Blue Collar is less energized than when it is grappling with the angst of the working class and their futile war against the system. Genre filmmaking requires less control and more trust in the fabric of the narrative beats, but Schrader’s ideology is inseparable from his storytelling. This is not to say that Blue Collar is not an electric viewing experience. Schrader has a great sense of propulsive momentum and a sharp edge in the structure of the film. Despite the characters being ploys for a greater message, viewers are sympathetic to their desires and dubious of their ambitions.

9. I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978)

From the mind of imaginative blockbusters pioneering groundbreaking technology, I Wanna Hold Your Hand represents the indie, D.I.Y. spirit of Robert Zemeckis. Infusing his populist influences and engineer-like filmmaking prowess, Zemeckis created a charming teen comedy crossed with a pivotal cultural boom in America in I Wanna Hold Your Hand. The director is desperate for a humanist and sincere film like this to break out of his current creative rut.

On the eve of The Beatles’ iconic performance on The Ed Sullivan Show that elevated them to American superstars, I Wanna Hold Your Hand follows the journey of six teenagers hoping to meet their idols. Throughout his career, Zemeckis was great at disguising heists and other genre capers as quaint character dramedies. He cares about what the teens learn about themselves in their frantic quest to meet John, Paul, George, and Ringo and the execution of the scheme equally. This contrast lends the film a momentous narrative that could easily talk in circles under the wrong hands. Even with a limited budget and inexperience in feature films, Zemeckis is assured in his direction. The sharp pacing and clear narrative structure paved the way for his heartfelt spectacle films in Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

I Wanna Hold Your Hand is ultimately committed to being an engrossing comedy above all else–never shying away from zany slapstick humor. The backdrop of Beatlemania is not used as a punchline for a pack of rabid teenagers, but rather, as a thoughtful window into American culture in the 1960s. Relating to its 1978 release, Zemeckis’ film operates as a time capsule of adolescent innocence that would be shattered by the political and social doom at the end of the decade.

10. Real Life (1979)

Whether in the form of stand-up, television shorts, or film, Albert Brooks is a comedic genius. His wit, introspection, and observational humor are marvelous and walk the fine line between a snarky humorist and curious artist in the most endearing fashion, and his criminally underrated filmography represents his artistry. Brooks’ feature film debut as a director, Real Life, is a remarkably creative and prescient portrait of America’s fascination with “reality.”

In the film, Brooks plays himself, a narcissistic director capturing the authentic life of an average family in Phoenix for an entire year until the counterintuitive tendencies of reality T.V. arise. Real Life is seamless as a pure comedy, as Brooks’ timing and delivery construction are at their peak. However, like all of Brooks’ films, he is not sweating too hard to make uninterested viewers laugh. For a rookie director, his instinct for camera place, especially in the context of a documentary filmmaker inadvertently being obtrusive in the narrative, is quite brilliant. He utilizes the concept of the director’s bias and act of manipulation that permeates filmmaking. Brooks’ eye for visual storytelling and unpretentious dissections of American culture announced him as a perennial comedic filmmaker. The glamor and obsession with reality television in 1979 is tame compared to today.

Furthermore, the insistence that this form of reality television is thought-provoking has aged incredibly well. Despite the veneer of a wholesome comedy, Real Life relishes in cynical satire–poking fun at the stuck-up visionary and the meticulous longing to be groundbreaking. Additionally, the romanticism of an innocent Americana dwelling in the suburbs juxtaposed with the artifice of Hollywood’s creation of dreams and idealist paintings on screen is the kind of ingenuity that Brooks consistently realized during his career.