5. The Stepfather (1987, Joseph Ruben)

The simplicity of Jerry Blake’s (Terry O’Quinn) scheming in The Stepfather seems absurd in 2023. In an age of hyper surveillance, militarized police, and pocket computers that perpetually track movement, it would be highly unlikely that a person could manifest a picturesque new life for themselves a few dozen miles away from the scene of a triple homicide they committed (and that everyone knows they committed). And yet, even now, The Stepfather remains a terrifying and wildly entertaining story of a psychopathic man unwilling to settle for anything less than the delusional ideal of the white picket fence American family.

The premise of the 1987 film is simple: Blake, motivated by some unresolved (and unexplained) childhood trauma as well as a healthy dose of hypermasculine entitlement, goes from Seattle suburb to Seattle suburb in search of widows with children, families upon whom he can graft his perverse fatherhood fantasies. When he is invariably disappointed by reality, he responds by preparing a new life in a nearby idyllic suburb and then murdering his current family.

The film opens in the immediate aftermath of one such murder—a gruesome scene in which his wife and two young children lay dead in the middle of a bloody living room. The story picks up in Blake’s next town, where he has already seduced a recently widowed woman (Shelley Hack) but is struggling to win over her grieving daughter (Jill Schoelen). Stephanie’s (Schoelen) intuition keeps her constantly on her toes around Jerry, setting the stage for a battle of America’s shifting values: the puritanical traditionalist vs. the progressive youth who knows that she and her mom would be better off on their own.

The Stepfather is a fully conceived idea built on incredibly convincing performances from O’Quinn and Schoelen. Kael lamented that this movie was likely to be underappreciated in its moment, which was mostly true. Roger Ebert gave the film two and a half stars, and it grossed a middling $2.5 million at the American box office. She attributed the movie’s underwhelming pop culture presence to its “placid surface that resembles B-picture banality,” but felt strongly that it was a “cunning, shapely thriller—a beautiful piece of construction.” To her, the film’s foundation of a “sharp” script, a skilled director, and a “special tension” between O’Quinn and Schoelen rendered this slashing thriller worthy of increased attention and consideration. Ironically, she closed her review by noting that the film felt “cruelly plausible,” a statement that might not have aged well, but still somehow feels right.

4. The Killer Elite (1975, Sam Peckinpah)

When it came to Sam Peckinpah, Pauline Kael admitted her bias. By 1975, Kael had known Peckinpah for a decade and, as she wrote in her review of The Killer Elite, she felt “closer to him than… any director except Jean Renoir.” In spite of, or perhaps because of, this closeness, the review reads more like psychoanalysis than it does pop cultural criticism. She was fascinated by Peckinpah’s particular combination of technical skill and embittered self-mythologizing—the way he grafted his considerable cinematic abilities onto revenge fantasy pulp as a stylistic “screw you” to the producing powers that be. According to Kael, in making The Killer Elite, Peckinpah finally landed the punch.

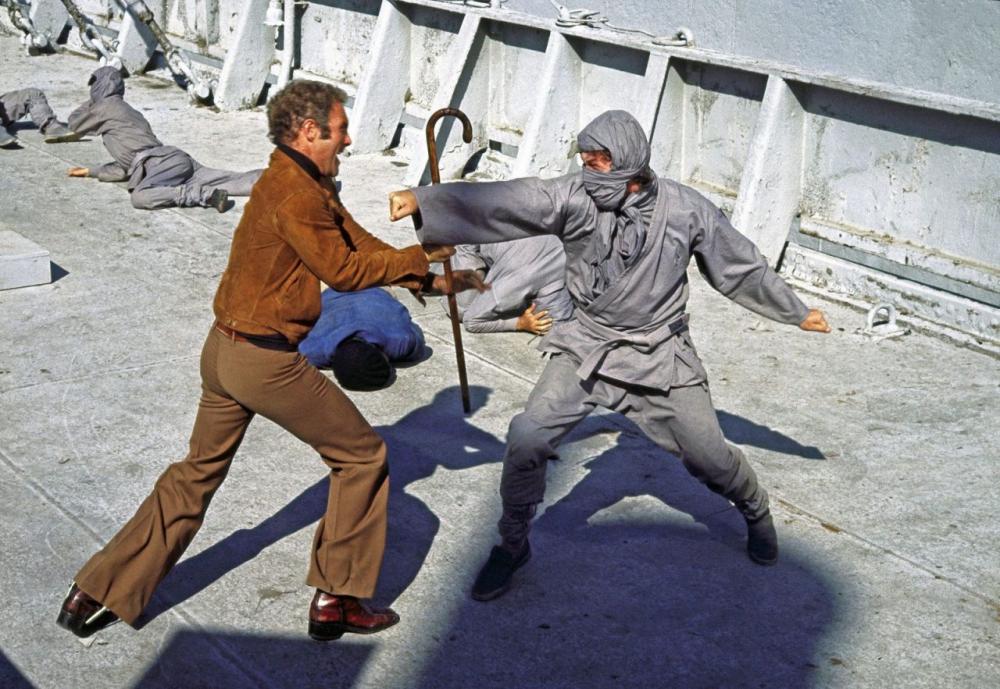

The film centers on Mike (James Caan), a for-hire man of violence out for revenge against George (Robert Duvall), his former partner and best friend. The pair work for a company contracted by the CIA to protect (or kill) persons-of-interest to the state. When George is offered greater wages to flip sides, he incapacitates Mike by shooting him in the elbow and the knee, causing Mike to suffer grueling months of hospitalization and physical therapy to regain his former strength. After taking opposing sides in a high stakes political operation involving a Taiwanese pro-democracy dissident, a small army of ninja assassins, and their two-timing boss, Mike and George find themselves hunting for one another and questioning the perverse morality of their profession.

Underwhelmed by the film’s convoluted plot, which she described as “shrouded in a dark fog,” Kael was nonetheless mesmerized by Peckinpah’s “poetic vision.” To her, the fog was actually part-in-parcel with Peckinpah’s criticism of corporate Hollywood, as “the fragmented story indicates how he feels about what the bosses buy and what they degrade him with.” Through the fogginess, she felt the film was without a wasted image. His action sequences left her transfixed, as if she were witnessing a “nightmarish ballet.” While she criticized Caan for lacking cold-bloodedness, she raved about the careful casting of character actors Burt Young, Gig Young, and Arthur Hill, each of whom represented critical components of Peckinpah’s mythology. This myth, resentful as it was, simply worked for Kael, who closed her review defending her friend’s indulgences: “The bedevilled bastard’s got a right to crow.”

3. Diva (1981, Jean-Jacques Beineix)

Diva is far from a perfect movie. Its elaborate plot follows a handsome young postman named Jules (Frédéric Andréi) as he knowingly and unknowingly finds himself in possession of two highly valuable tapes. The first—his bootleg concert recording of famed American opera singer Cynthia Hawkins (Wilhelmenia Fernandez)—is desired by two relentless Taiwanese producers looking to get their hands on the only known Hawkins recording. The second—a cassette slipped into his satchel by a woman being chased by assassins—incriminates the police chief (Dominique Pinon) as the head of a sex trafficking ring. The ensuing collisions require numerous leaps in logic and even a “punkers deus ex machina” to resolve themselves, but nonetheless, Pauline Kael enthusiastically endorsed Jean-Jacques Beineix’s directorial debut as a “glittering toy of a movie.”

There are characters in this film that confuse and that Beineix seems generally unconcerned with exploring. Gorodish (Richard Bohringer)—the deux ex machina in question—is the biggest mystery. He’s positioned as a religious figure of sorts—a weird spiritual sibling to Bodhi in Point Break, but if Bodhi were brooding and obsessed with cigarettes and 50,000 piece puzzles instead of surfing. And what is his relationship to Alba (Thuy An Luu), the spunky fourteen year old Vietnamese girl who lives with him? Does her presence (as well as his fluency in navigating the criminal underworld) indicate that he’s somehow benefitting from the trafficking ring he spends the second half of the movie tearing down? Kael called him “a tease of a character… and when he takes over, something gets dampened.” It’s hard to tell if Beineix thought Gorodish a false prophet, a guardian angel, or some combination of both.

Additionally, the women in this film could have more to do than serve as fixtures of male desire. There’s an illustrative De Palma-esque shot in the third act when a random beautiful blonde walks above a subway grate and has a brief Marilyn Monroe moment for no reason. Beineix doesn’t quite give into his depravity like De Palma does, which somehow makes the shot even creepier, or at least less self-parodying. But even Cynthia, whom Kael admires for her “awesome” beauty and powerful stage presence, is written only to embody some dream of artistic purity. Beneath the surface, she seems vacuous. She and Alba both nearly approach complexity, but never quite get there—Cynthia because she’s too clear, Alba because she’s too abstract.

And yet, confused and manipulated as one might feel by all of this, there is so much to love in this film. Beineix conjures images of Paris that gag a viewer—so many locations shot to death are resurrected. Kael described his style as “so smooth yet so tricky and hip that Beineix might be Carol Reed reborn with a mohawk haircut.” The movie’s humor is delightfully absurd, often derived from playful nods to films of Beineix’s fancy.

Charmed by his buoyant attitude, Kael wrote that “Beineix doesn’t force connections on us. Everything is deft, flamboyant yet light.” Andréi’s affectionate and enchanting performance as Jules drives much of the film’s joy. He successfully makes it seem strange that opera isn’t chic pop art, which is an accomplishment in itself. And in the end, Beineix’s true accomplishment is that music and romanticism find a way to shine through without sacrificing themselves to trivialities of purpose or plot.

2. We Still Kill the Old Way (1967, Elio Petri)

Pauline Kael wasn’t impressed with Elio Petri’s 1971 Academy Award winner, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion. She found the film “extremely dislikable,” criticizing Petri for misusing suspense and making it “too nasty and kinky” for the political allegory to land. What failed Investigation is precisely what she admired about its predecessor, We Still Kill the Old Way. She lauded Petri for his ability to keep the audience on a string, writing that he “tightens the hold on us as the hero becomes more desperately helpless and we begin to realize that there is no way out.”

We Still Kill the Old Way is carefully composed around its hero’s sexual and political frustrations. When three poor Sicilians are wrongly arrested for the murder of two young men, communist professor Paolo Laurana (Gian Maria Volonté) and newly widowed Luisa Roscio (Irene Papas) ensnare themselves in a claustrophobic network of local lawmakers, lawyers, clergymen, and Mafiosos to expose the island’s underlying corruption. Laurana, motivated equally by his leftist politics and his lust for Luisa, seems to struggle madly against Sicily itself. Its towns and cities, politicos and peasants, and even the landscape all seem to conspire against him. The closer he gets to the truth, the farther he is from quenching his insatiable thirsts.

Despite her misgivings about Investigation’s kinkiness, Kael always loved a perverse crime thriller, which is exactly what she found in Petri’s sun scorched paranoia masterpiece. The will-they-won’t-they between Volante and Papas blew Kael away. She argues that in one shot of a desperate knee grab, Petri extracts “more desire and passion and sex… than in several recent pictures full of beds.” Petri and cinematographer Luigi Kuveiller do more showing than telling in general, utilizing their extensive technical skill and sensitive knowledge of the landscape to “[expose] entangled social relations without comment.”

1. Blow Out (1981, Brian De Palma)

Like We Still Kill the Old Way, Blow Out follows a truth telling citizen bucking against the systems built to silence. Where sex, politics, and landscape drive Petri’s plot, Blow Out’s tension surfaces from its relationship to sound. Jack (John Travolta) is a sound mixing technician working on small exploitation films in Philadelphia. (Side note: one could make an earnest argument that Blow Out boasts the best ever use of Philly in film.) While out in the suburbs recording the sounds of the night, Jack witnesses and records a single-car crash in which a leading presidential candidate is killed. He and Sally (Nancy Allen), the crash’s lone survivor, become convinced of foul play. Using his tapes from the night in question and his professional prowess, Jack pushes himself to the limit to save Sally and unearth the conspiratorial truth.

Kael so frequently poured acid on films that the praise she heaps on Blow Out destabilizes the reader like Shakespeare breaking iambic pentameter. “I think that Brian De Palma has sprung to the place that Altman achieved with films such as McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Nashville and that Coppola reached with the two Godfather movies – that is, to the place where genre is transcended and what we’re moved by is an artist’s vision.” With respect to admirers of Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Scarface and De Palma’s cadre of iconic films, Blow Out distills the ornery auteur to his absolute apex, at least according to Kael. Jack’s occupation offers a useful vehicle for De Palma and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond to show off their own technical chops.

There is a litany of “how did they do that?” shots, including a pivotal moment when the camera spins from within a tape Jack is splicing into a makeshift Zapruder film. And yet, despite the flashy displays, each shot seems to serve the intensity bubbling beneath Jack and Sally’s journeys. This isn’t 1917, where the story is reduced to a vehicle for the lens. As Kael raves, De Palma and Zsigmond’s “pyrotechnics and the whirlybird camera are no longer saying ‘Look at me’; they give the film authority.” There is scarcely a word of criticism for De Palma in Kael’s review, which reads something like a proud parent glowing about her virtuosic child.