Sidney Lumet was one of the most prolific and versatile American filmmakers of all time, a man and an artist of seemingly infinite talent for reinvention, gifted with a truly admirable curiosity for all types of people, characters and stories; and a willingness to branch out into different genres and territories.

So it’s not a surprise that, in such a vast and rich filmography, among the many classics he gifted the world and that have gained the recognition they deserve, there’s still many more unsung gems worthy of discovery.

So let’s dig a little into the treasure trove that is this career for 10 great Sidney Lumet Movies You May Not Have Seen.

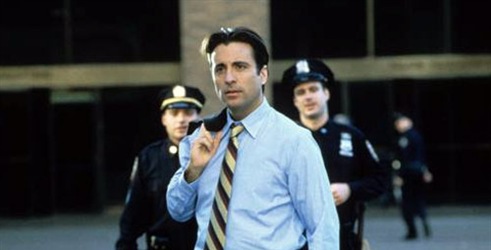

10. Night Falls On Manhattan (1996)

Sidney Lumet is just as iconic and formative a figure to the New York cop movie as Martin Scorsese is to the mafia film. There’s perhaps no other filmmaker who has shown a more consistent interest in every aspect of police work, particularly the institutional corruption embedded into its structure and the moral dilemma that entails.

It’s a theme the director returned to again and again throughout his career, resulting in some of his most acclaimed classics (namely “Serpico”) and a handful of relatively obscure gems in need of rediscovery. “Night Falls On Manhattan” is one of his most nuanced explorations of this pet preoccupation, starring Andy Garcia as an ambitious and upright District attorney who stumbles upon a police corruption investigation that may implicate his father, as well as the father’s partner (respectively Ian Holm and James Gandolfini, both terrific).

What’s most admirable about Lumet’s recurring, relentless interest in the machinations of the police world and it’s inherent destruction, is that he always found new ways to approach it dramatically, never allowing it to become repetitive, giving each movie a unique perspective. “Night Falls On Manhattan” is one of his most impressive juggling acts: the film works as an intriguing morality play, a father/son relationship drama and just a tight procedural.

9. The Morning After (1986)

Of all the great New Hollywood titans, Lumet is probably the most modest; there’s no grand epic to his name, no myth behind the stories of obsessive vision chasing nor, most rare, a preciousness with regards to material. Lumet was a director who put as much effort and care into an adaptation of Eugene O’Neill as he did into one of Agatha Christie.

Whether that carefree nature was due to a lack of better options, a necessity to keep working no matter what or a genuine interest in elevating subpar material is unclear and irrelevant, the fact remains that, curiously, for one of the most gifted American filmmakers of all time, Lumet was never one to shy away from trashier stuff.

“The Morning After” is one of the most enjoyable examples of his sillier side, telling the story of an alcoholic actress (Jane Fonda) who wakes up one day next to a dead body in an apartment she doesn’t recognize and flees in fear of getting the blame. On the run, she tries to put the pieces together to find the real killer, while getting mixed up with a retired cop (Jeff Bridges).

It’s a fun and intriguing story on its own, but it would be much less remarkable a film were it not for Lumet’s subdued approach, focusing on the two wonderful actors at the centre and letting them do the heavy-lifting.

8. Running On Empty (1988)

Lumet had an extensive theater background before transitioning into film, which no doubt helped him become an exceptional actor’s director. Even though he had a wildly varied career, moving through several genres and applying a remarkable flexibility of style, there was always one constant: excellent performances.

In fact some of the most iconic screen performances of all time exist thanks to Lumet, from Al Pacino in “Dog Day Afternoon” to Peter Finch in “Network” (or the entire cast of that movie, really). River Phoenix’s turn in “Running On Empty” may not have reached that level of acclaim in collective cinephile culture, but it’s every bit as brilliant as any of the best performances in Lumet’s filmography.

This relative obscurity of both the film and Phoenix’s exquisite performance may be due to the fact, unlike the other movies mentioned here, that “Running On Empty” is not a fleshy crime film or a flamboyant satire, but a quiet, intimate drama about a family of activists on the run, that Lumet handles with acute specificity and sensitivity. But at the end of the day, it’s really Phoenix that makes the film: raw, real, transfixing.

7 and 6. The Anderson Tapes (1971) and The Hill (1965)

Given that talent for directing actors, then, it’s no wonder that Lumet established a creative partnership with several great performers, but none longer or more fruitful than the one he enjoyed with Sean Connery, whom he worked with five times.

The two best out of the five are “The Anderson Tapes” and “The Hill,” both of which showcase Lumet’s often unheralded mastery of film language. As said before, given his background in theater, this filmmaker’s most celebrated movies tend to eschew formalism, opting for as minimally obtrusive a visual language as possible, favoring muted style and simple staging. Such choices could sometimes be mistaken for sloppiness, a lack of acumen behind the camera. But as Lumet explains in his essential book “Making Movies,” he always opted for whatever aesthetic best fitted the story he was telling – naturalism wasn’t simply a default.

“The Anderson Tapes,” a stylish paranoid thriller/heist movie hybrid, finds Lumet at his most playful, employing a timeline jumping narrative (intercutting the planning and preparation for the heist with the police investigation in it’s aftermath), and a typically excellent score from Quincy Jones, all of which amount to a very entertaining caper.

“The Hill,” on the other hand, is one of the most grueling films in Lumet’s oeuvre, a punishing prison drama about a group of British soldiers suffering ever-more severe abuse at the hands of their sergeant. But if that sounds simply too unpleasant to endure, don’t worry; this film might just be Lumet’s most visually bold picture ever, with staggeringly expressive black and white cinematography, creating a sense of unease through dutch angles and deep focus framing. It’s a magnificent visual experience, unrivaled by anything else Lumet ever did.