6. Adaptation (2002)

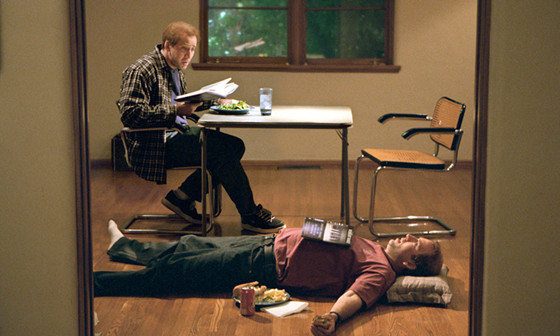

Meta-fictional neurosis reaches its peak with Charlie Kaufman’s Adaption. The film, directed by Spike Jonze and written by Kaufman, centres around a self-loathing writer named – Charlie Kaufman. If Kaufman wasn’t happy with simple meta-fiction, it’s as if he blew his self-involved imagination out onto the page with a revolver. Nevertheless, this explosion of self-image, self-hating, and fictional world-making is a remarkably funny and one-of-a-kind piece. Nicolas Cage plays Kaufman, faced with the burden of adapting a novel for the screen, Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief. It’s in fact a real book written by a real woman named Susan Orlean, someone who’s book was assigned to Kaufman for adaption following his success with Being John Malkovich (1999).

Things taken a turn for the weird when Kaufman’s fictionalised twin brother, Donald Kaufman (also Cage), is writing a screenplay, one that proves far more successful than his loser brother’s. Charlie watches bemused and frustrated as his brother writes a cliche-ridden genre picture, structured around the self-help insights of real-like screenwriting mentor, Robert McKee – who naturally becomes a character in the film, portrayed by Brian Cox. Kaufman’s McKee is a cult leader for lousy screenwriters, teaching his students the rules of writing (rules that the real Kaufman is outwardly against, such as formula and genre; even the final voice-over in the film is a slap to the real McKee who infamously denounces voice-overs as lazy). Charlie and Donald become the two forces of writing; one loyal to the imagination’s freedom, the other willing to sell-out to profitable rehashes.

In short, Charlie Kaufman’s own internal struggle about writing becomes the basis of the film. Perhaps this style of absurdism is not to everyone’s taste, but Adaption is an anarchic, wonderful watch. Kaufman’s imagination takes us into the depths of a surreal self-awareness, where having to structure one’s own life and having to structure one’s screenplay are equally difficult – equally crazy.

7. Holy Motors (2012)

Leos Carax’s Holy Motors is one of those films that redefine the rules of the game. It’s a film about the nature of performance and filmmaking – and yet, it ingeniously subverts its own material. Blending fantasy with meta-fiction, the film is a dark and rapturous display of how we are all actors in our own lives.

Denis Lavant plays the ambiguously named Mr Oscar, who at first appears like any ordinary business man; he steps out of his beautiful house and takes a limousine to work, a series of scheduled ‘appointments’. As the film progresses, it becomes clear (or not so clear) that Mr Oscar is an actor. He performs various roles throughout the film – as an elderly beggar, a worried father, a Chinese gangster, even a red-haired maniac who terrorises the streets of Paris (a.k.a Monsieur Merde, a role that Lavant played in Carax’s 2008 film Tokyo!). However Mr Oscar performs all these roles in public, in the real world – on the streets, the suburbs, the sewers – without any cameras recording him. Mr Oscar performs for nobody, no audience or critics; rather they are contained by his own impulse to act them out, his own commitment to the various roles.

The film’s surrealism only builds when he encounters an manager-type figure, who questions whether Mr Oscar is getting too ‘tired’ to keep performing. Mr Oscar simply replies that the business is changing, the cameras are getting smaller and smaller to the point in which they’re no longer visible.

As much as the film dissolves the boundaries between the fictional worlds within it (the story of a man who performs stories which may or may not be real in an unreal film…), Carax also makes a melancholy remark on the changes in the film industry – how new technologies alter reality. There’s even a scene where Mr Oscar performs in a motion capture suit, running on a treadmill – his movement echoing back to the Eadweard Muybridge photos which appear at the start of the film. Cinema’s history is expanding, evolving; and Carax adopts some of the changes while also mourning what Mr Oscar claims to mourn, a long-lost purity, ‘the beauty of the act’.

8. Berberian Sound Studio (2012)

Peter Strickland is masterful when it comes to the ambiguities of discomfort. Although his use of repetition can often be stronger in his shorter films than his features which have a tendency to drag, Berberian Sound Studio is an nsidious film which explores the horrors of filmmaking. Toby Jones plays a British sound engineer, Gilderoy, who has been brought over to a studio in Italy to collaborate on a gratuitously violent giallo film.

At the start, Gilderoy’s unease appears as a form of cultural displacement; his meek British demeanour comes to clash with the brashy, volatile nature of the Italian studio. But his sense of reality is soon undermined: finding out that the flight that brought him to Italy never existed, nighttime terrors where he envisions himself inside a film about his own life, not to mention the fact he inexplicably becomes fluent in Italian overnight. Strickland delivers a discomforting, purposefully slow film about becoming overwhelmed with a sense of otherness, experiencing oneself as someone else, and losing oneself in the act of filmmaking.

This may sound like an art-house Blow Out (1981) or any number of psychological thrillers where reality and dream begin to merge; but what’s unique about Berberian Sound Studio is how there’s a reversal of the obvious. Everything that is normally out of view in a film – the mechanics of the camera, the celluloid, the dubbing – actually take up the majority of the footage. Most of Strickland’s film is watching strips of celluloid passing back and forth through heavy machinery. And yet the film being made, the giallo film which Gildeory and the studio are constantly working on, is never shown, always out of view, leaving us to question what it is we’re actually watching.

9. Peeping Tom (1960)

Like Strickland’s film, Michael Powell also presents filmmaking as an obsessive, voyeuristic dark art. Revolving around a psychopath who murders women while also recording their murder on his portable camera (presumably what would happen if Andy Warhol and Charles Manson had a child together), Peeping Tom is an underrated and exceptional thriller, where the eye of the camera and the eye of the killer converge.

The anti-hero Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm) is the pathological product of a pathological upbringing, his father having experimented on him as a child, making home movies about how his son reacts to terror. Result: a son who develops an impulse to kill the women who arouse him, and to record the fear on their faces as they meet their demise. The climax where Lewis records his own suicide is a fascinating spectacle – impaled on his own tripod as he runs towards the lens – the film itself ending because the recording eye (that of the main character, his physical self, his ‘I’) has been destroyed.

Peeping Tom is a bleak, sometimes silly, sometimes sad tale about the consequences of committing one’s whole life to filmmaking. Martin Scorsese has grouped Peeping Tom with Fellini’s 8 1/2, claiming that both films deal with ‘the objectivity and subjectivity of [filmmaking] and the confusion between the two’; where they differ is that Fellini celebrates the glamour of cinema, whereas Powell demonstrates how the camera is also a tool of violation (a violent phallus as some Freudians argue?), how it can irreparably severe the human relationships that try to come between an artist and their camera.

10. Broken Embraces (2009)

Known for his mix of campy anarchy and soap-opera-style melodrama, Pedro Almodovar’s films are also engaged with the process of filmmaking. His last feature, Pain and Glory (2019) centres around a declining filmmaker, and All About My Mother (1999) ends with a tribute to Almodovar’s favourite actresses (‘To Bette Davis, Gena Rowlands, Romy Schneider … To all actresses who have played actresses’). However Broken Embraces is more openly preoccupied with the act of assembling images together – forgotten or lost fragments from the past, trying to use them to navigate one’s future.

The film is told through a series of flashbacks, those recollected by screenwriter Mateo Blanco, who has taken on the new name of Harry Caine (played by Lluís Homar). He recalls a fatal love triangle between his actress and muse, Lena Rivas (Penélope Cruz) and her husband, the possessive millionaire Ernesto Martel (José Luis Gómez). Martel goes out of his way to sabotage the film that Harry and Lena are working on, the film he is partly funding, and he’ll stop at nothing, even pushing his beloved wife down a set of stairs (like any good soap opera).

Looking back at these tragic times, and his film being butchered in the editing room by Martel, Harry Caine decides to re-edit the film now that time has passed, in loving tribute to Lena who didn’t survive the scandal. Though Harry is now blind, he is dedicated to put things right, even if only possible through re-editing his film. With the help of his son and agent, he blindly reassembles the fragments of the past.

In Broken Embraces, filmmaking is a somewhat nostalgic venture, where memory and film become a similar medium. The scene where Harry embraces his television screen is especially powerful if not uncomfortable; knowing that the screen is paused on an image of Leda, he presses his hands to the screen and caresses her image. The fact he’s blind almost suggests that he’s trying to recall her through the shape, texture and contouring of her face. But this goes against the fact that he’s handling a screen and not a real face – something smooth and textureless. The border between the real and the represented becomes poignantly overcome, as Harry offers all that he can offer – a broken embrace.

These films do not simply present fiction as another world, but as something that’s inextricably tied to our own lives; it helps us live in a world that at times seems no less fictitious, no less artificial. These films pay tribute to the craft as well as to the films and filmmakers who argue that it’s impossible to think about life, fantasy, memory, without films.