“Didn’t you ever hear of women’s lib?”, a young Jodie Foster’s Iris scorns in the 1976 psychological drama Taxi Driver, as she intensely spreads jam on her toast in a diner sat opposite the film’s titular damaged male character, Travis Bickle. And it was a vital question to raise. While Bickle insists that she should leave the life on prostitution, abuse and crime she’s found herself in, she is unusually calm. She knows it’s her mess, and her choice to leave it; if she chooses too.

During the late 1960’s and and into the 1970’s, the women’s liberation movement came alongside the many other social upheavals and protests of the era, signifying global change and calling for things such as equal pay, legal equality and recognition for sexual discrimination, with shockwaves being felt in the then (and arguably still) male dominant film industry.

The picks on this list are a great starting point for delving into the work of the often unsung female heroes from the decade, with titles ranging from low budget independent films made on the fringes of the studio system to mainstream hits. However, despite the greatness of these films, the women behind them and their influence never seem to be included in the pantheon of filmmakers so often cited from the decade, which is not only a shame, but truly baffling.

1. Wanda (1970)

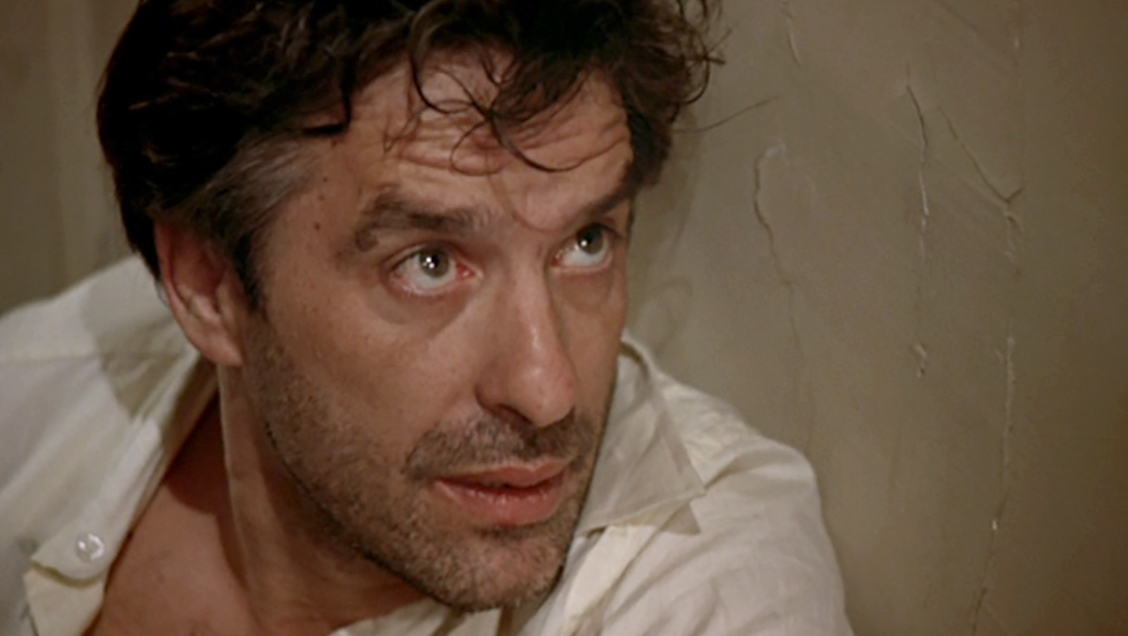

Famously described as ‘the female counterpart to John Cassavetes”, Barbara Loden made her name in the melodramas of her husband, Elia Kazan. When the opportunity arose for her write a feature, her script about a poor housewife wandering passively into a relationship with a bank robber didn’t attract many directors, so she did it herself. And the result was one of the most influential cinéma vérité films of the decade.

Loosing her job, child and husband, Wanda Goronski’s life goes from bad to worse as she wanders through the rural parts of Pennsylvania. When she comes across Norman Dennis, a thief she mistakes for a barman, Wanda desperately clings to him despite his abusive nature. Eventually, she is embroiled in a bank robbery he carries out.

With most of dialogue improvised and Loden’s central character being largely unresponsive to goings on, many found this debut to be incredibly polarising and oftentimes dull. However, it’s exactly those elements that critics claimed were ‘boring’ that make this such a special film. Informed by Loden’s own bouts of aimlessness, the film so perfect depicts that feeling that it’s hard to think of a better representation of depression on screen at the time. Letting events collapse around her and only showing interest in people she knows will hurt her starkly depicts Wanda’s state of mind. It’s a mindset of everything having gone wrong, and feeling powerless to change it. The oppression she’s been so downtrodden by was part of a system that proved so unbreakable that succumbing to Norman was a logical next step.

During the robbery at the end of the film, once Wanda is relegated to nothing more than an onlooker, her aimlessness restarts after Norman’s exit, and it’s on to the next sect of wayward people. All the while, the scenes of Wanda leaving her child and job at the beginning permeate throughout, and underpin the film in the most heartbreaking of ways.

The fact that Loden never starred in or directed another feature is a travesty. Her turn here is truly transformative and effecting, and echoes future women’s lib sentiments that would come into cinema later in the decade.

2. Diary Of A Mad Housewife (1970)

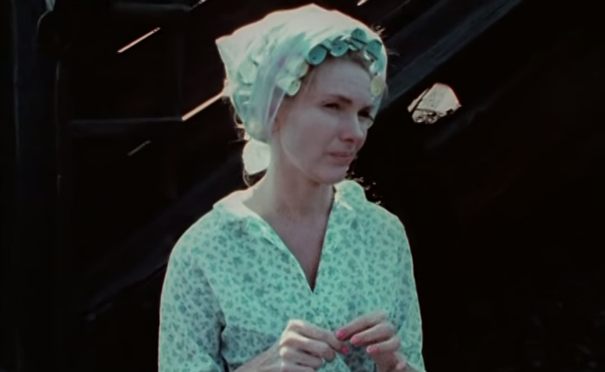

Along with Curtis Harrington and Paul Mazursky, the director of this next film is undoubtedly one of the best directors of female performers and writers of the era. Frank Parry really let their work flourish and, with a great screenplay written by his wife Eleanor and fantastic central performance by Carrie Snodgress, crafted an insightful peek behind the curtain of a woman’s psyche in a loveless marriage.

Based on Sue Kaufman’s novel, Diary Of A Mad Housewife follows Tina Balser (Snodgress), a smart, socially conscious woman who is constantly berated and demeaned by her husband Jonathan (Richard Benjamin), an emotionally abusive lawyer. After an affair with the equally childish George (Frank Langella), Tina finds a way to come out on top.

Though the above description may seem as downbeat as Wanda’s, Tina is a fundamentally different character to Goronski in the sense that she has this seething, bubbling anger toward her partner politely stowed away for the majority of the film. It adds to the sense of a culminating oppression that brings the audience in on her level, while putting them on edge as Jonathan’s behaviour becomes even more ridiculous, waiting to see how Tina will respond.

However, Eleanor Parry structures the story with such a deliberately steady pace that when Jonathan breaks down at the end, confessing to an affair and large loss of money without knowledge of Tina’s affair, it feels like something of a victory. From the beginning, it was clear that Tina didn’t need the validation of men to function; Jonathan gave her none, and she sought out George for her own pleasure, regardless of how he treated her. So, when Jonathan finally breaks, it feels like like Tina coming out on top, all the while keeping her cards close to her chest and not informing him of her affair. In a scene that could’ve predictably ended in a shouting match, Eleanor Perry’s brilliant writing creates a sense of dread as Richard succumbs fully to Tina’s mercy in a fantastic role reversal.

Though small scale, the film was actually distributed widely by Universal Pictures, leading to many awards nominations for Snodgress’ central performance, including an Academy Award. Despite not inspiring great change in gender representation and having since gone overlooked, it remains a key film for understanding the plight of women during the decade.

3. Puzzle Of A Downfall Child (1970)

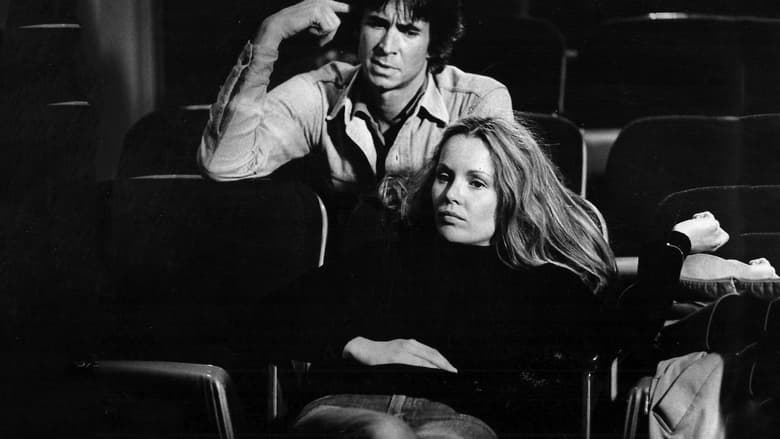

This entry sees the introduction of Carol Eastman to this list, a great unsung hero of the era who penned some of the most influential films of the decade. However, her work on the likes of Five Easy Pieces and Model Shop were often overshadowed by her pen name Adrien Joyce. It’s a real shame, as her work here is a fantastic female character study that only Eastman could’ve written.

Former top model Lou Andres Sand (Faye Dunaway) retells her life story to her old friend Aaron (Barry Primus) for a film he intends make. Charting her start in the industry, through to her botched wedding to ad exec Mark (Roy Scheider), and subsequent drug fuelled downfall, Aaron realises the memories are fragmented, and attempts to help Sand piece them together, leading to shocking revelations.

During the late 1960’s and early 70’s, films such as this would usually either not have been made at all, or would have been restructured to fit a male centric narrative. Thankfully, Eastman’s script made it through the cracks with help from director Jerry Schatzberg, and it’s heartbreaking nature (based on real life tapes the director had recorded with his friend, iconic model Anne St. Marie) made it’s way to the screen.

Eastman strikes a perfect balance between presenting Sand’s descent into alienation and her independence, creating an ominous sense around the film as she boldly makes her way through an industry that at first seemed alluring. As we learn of her past traumas later in the film, the entire story takes on an even more disturbing guise, a clever form of restructuring what’s happened before.

Never reliant on a male character, Eastman gives Dunaway’s Sand full agency over proceedings, in a carefully pitched performance that sees her character through nearly two decades. It’s fascinating how much the actor transforms over the course of time, creating a stark contrast between her wide eyed (yet still eerily cautious) persona at the beginning of her tale and her truly broken down shell of a person at the end. It’s a vital piece of work that was necessary at the time to display the adverse effects that certain industries have on their stars, with problems they often struggled with in silence.

4. The Heartbreak Kid (1972)

With possibly one of the most prolific runs of films through the decade and into the 1980’s, former Mike Nichols comedy partner Elaine May lead the way for female directors in Hollywood at the time. Turing to directing with the hilariously sweet A New Leaf in 1971, she proved that her sharp wit and sense of character development made for a new breed of comedy, perhaps best exemplified here.

Her sophomore directorial effort follows Lenny Cantrow (the late great Charles Grodin), a pompous and lazy salesman, as he navigates his new marriage to Lila (May’s real life daughter Jeannie Berlin). On their honeymoon, he realises just how different the two are and, after coming across the young and free spirited Kelly (Cybil Shepherd), hatches a plan to leave Lila. Very soon after, Lenny’s stupidity and selfishness gets the better of him with hilariously awkward consequences.

Though the above description seems as if it could fit any stock mid 00’s comedy, May’s unique eye for these flawed characters is genius in the sense that it brings the audience in on their level all in relation to Lenny, who himself is possibly the most flawed. However, May never structures the film in such a way that constantly points that out. His awfully plotted plan falls apart around him, from manipulating Lila to stay in the hotel room as he seeks Kelly, to breaking up with the emotionally volatile Lila in public after only 5 days of marriage. May makes sure the audience understands just how shallow Lenny is from the get go through a fantastically clever montage of Lenny and Lila’s courtship at the beginning of the film, which goes by with the same abrupt pace as the as their relationship and marriage. It perfectly sets up the film with a key insight to Lenny’s selfishness.

Along with A New Leaf, The Heartbreak Kid went a long way in establishing a new type of Hollywood comedy for the 70’s. Mixing the matter-of-fact storytelling from the likes of The Graduate with the playfulness of Neil Simon’s screenwriting, May worked to fit the romantic comedy, a genre that seemed to have little space for progression up to this point, into the popular films of the decade, which were known for their hard hitting and realistic style.

5. Play It As It Lays (1972)

Writer Joan Didion has been a mainstay of Hollywood culture since the 1960’s, with her many fiction and non fiction writings providing a fascinating insight into California at the time. Her incredibly unique style is still unparalleled, and her 1972 screenplay Play It As It Lays is a great example of the way she could structure a story through a shockingly real depiction of the film industry.

Maria (Tuesday Weld) recounts her life in L.A. as a successful actress, hailing from a small town. Told in flashback from her residence in an asylum, she charts the cruelty of her husband Carter Lang (Adam Roarke), her numerous affairs with increasingly insecure men, and friendship with B.Z. Marshall, a similarly depressed man who is her only ally.

The etherial nature of Didion’s writing here set the standard for a lot of similar Hollywood centric films, influencing the likes of Terence Malick and David Cronenberg, as she effortlessly strips away glamorous preconceptions of the industry to create a gripping story that plays out with a dreamlike pace. All the characters are so well layered and communicated to the audience cleverly, from Maria’s major anxieties being subtly displayed throughout, to the flaws of the men she receives pleasure from, and how that affects their experiences and mental states. The almost stagnant, procedural flow of the film puts the audience right in the same mood as Maria’s, meaning they’re with her on every step.

The character of B.Z., a role that Perkins’ really shines in and breaks away from his typecasting at the time, works to juxtapose the above characters, yet remains a bedrock for Maria. Though an openly gay man, the anxieties that plague him mirror Maria’s, all the while with Los Angeles acting as a character of it’s own, and often the impetus for these struggles.

Didion’s writing pairs perfectly with Tuesday Weld’s central performance, using Maria’s point of view, albeit distorted by depression, to show what the male dominated industry really amounted to behind the scenes. Using that to structure meaning behind the main characters struggles makes Didion’s assessment all too real, despite being fiction. With both the book and screenplay of Play It As It Lays, Didion proved to be one of the most unique storytellers in Hollywood at the time, prepared to put her honest, real feelings about it out in the open in the most interesting of ways.