6. Veteran (Ryoo Seung-wan, 2015)

From the slick opening moments of Veteran, the films immediate objective is clear: to entertain. Seung-wan’s film is remarkable in the pace it moves at, the editing is dynamic and the cinematography is slick – good looking people drive good looking cars and have great looking fights.

It is a direct and uncomplicated film, in the finest possible sense. The plot is simple, the antagonist is despicable and the heroes objective clear. Veteran follows Seo-do Cheol, a maverick cop desperate to bring down an heir to wealthy corporation – Jo Tae-oh. The film leaves the audience little room to ponder – themes of class are within the text but are dealt with less subtly than, say, Burning (Lee Chang-dong, 2018) – but that is a non-issue. Veteran is meant to be enjoyed as a visceral piece of work: this is a film to be felt.

Its ambition is incredibly admirable as well. The film mixes realistic and grittty fighting with moments of broad comedy. This is refreshing as regularly films within the action genre can take themselves too seriously, looking ridiculous as a result. Veteran forgoes this completely, with one particularly unforgettable sequence sees a man fight with what look to be a pair of sketchers. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker, the tones of Veteran could clash and undermine each other. However, Seung-wan tones reinforce each other creating dizzying moments of entertainment where the audience doesn’t know whether to be shocked, laugh or scream in delight – often all three occur.

This is a truly rare piece of work. A film that wants to do it all: thrill you, make you laugh and even move you in places. A blockbuster this ambitious and, largely, successful deserves a mention. There is a reason it is South Korea’s 4th highest grossing film of all time. Seek it out.

7. The Sea Village (Kim Su-Yong, 1965)

Kim Su-Yong’s The Sea Village focuses on harsh life of a fishing village. The men regularly risk their lives to fish, returning with little to no reward or worse – they do not return at all. However, director Kim Su-Yong focuses less on the men, preferring to observe the impact on the women they leave behind. Su-Yong’s audience views the film from the perspective of Hae-soon, a young woman who is informed that her newly-wed husband has died at sea.

Hae-soon is caught in a ruthless world, one that takes a lot and gives very little. After the death of her husband, she spends her ensuing days fighting off men in the village proposing to her in aggressive and domineering fashion. Su-Yong neatly contrasts Hae-soon’s situation with that of her own widowed mother-in-law. In a touching moment, her mother-in-law informs her to start a new life with a miner as she deserves a second chance at love.

The film is shot in gorgeous black and white widescreen. Some may take issue with representing a small, insular community on such a large screen. However, Su-yong uses this technical choice to immerse his audience in the world of the characters. This is most effective when these beautiful images work in tandem with the films meticulous soundscape. Imposing waves can be heard crashing and harsh winds rip through the speakers. It is a tough life the characters have to live and the audience are made to feel as if they are living it to thus sympathising deeply with Hae-sun, her family and their situation.

Additionally, the widescreen cinematography helps to communicate the loneliness of the women that are often left behind. Vast empty space is seen on the screen, whether it is the seaside, the dense forest or the rocky mountains of the miners. Nothing ever seems to be out there no matter how hard or far our character’s search. These timeless themes of losing loved ones and searching for companionship are part of what makes the Sea Village such an astounding piece of cinema to revisit even today.

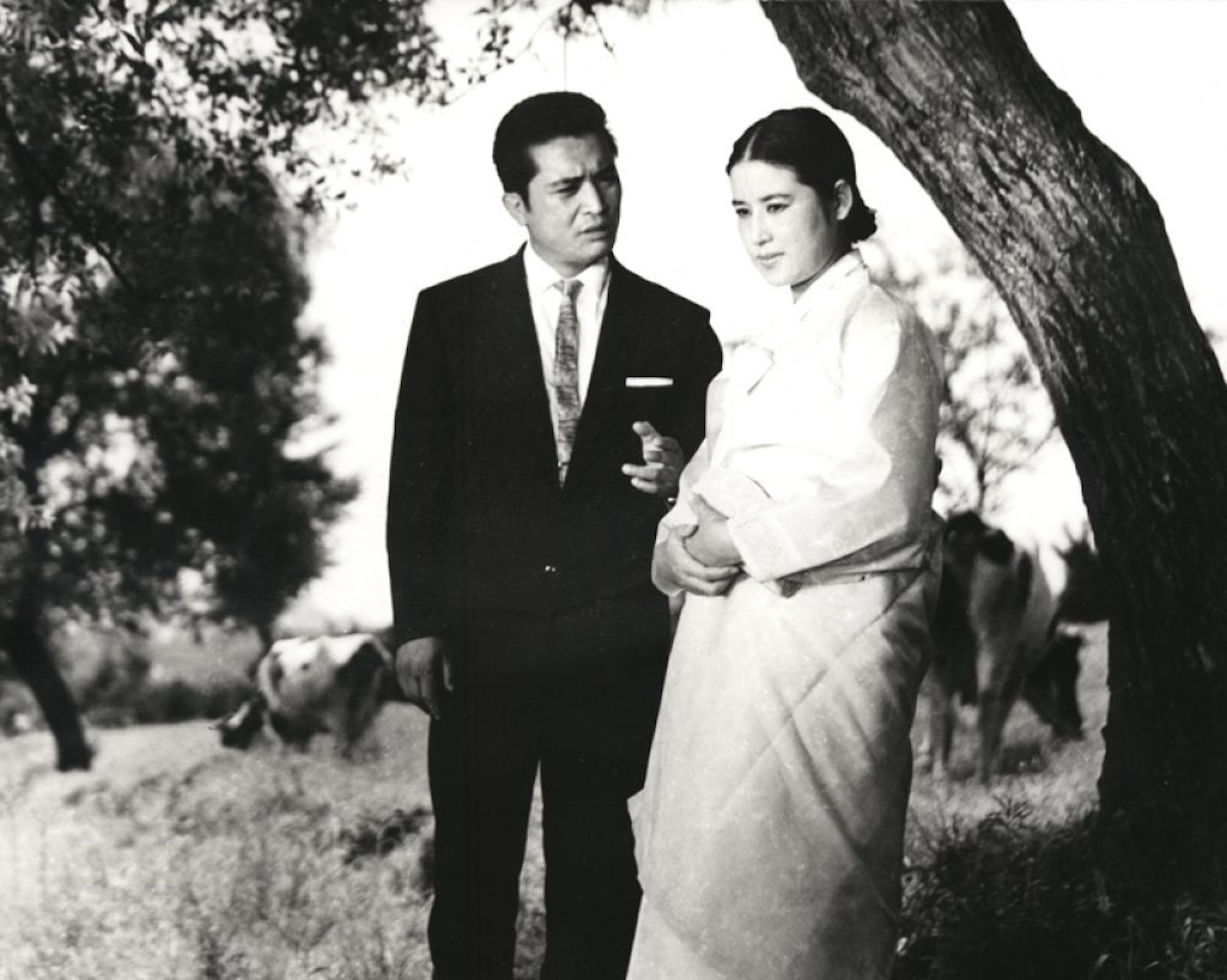

8. The Houseguest and My Mother (Shin Sang-ok, 1961)

The Houseguest and My Mother tells the story of a young girl – Lim Ok-hee- viewing an emerging relationship between her widowed mother and Mr Han – an artist – who was a friend of her deceased husband.

Importantly, Shin Sang-ok’s film takes a detailed look at the social implications of the situation. The film exists in an environment where gossip spreads fast and to be a victim of rumour could tarnish your reputation. The Mother and Mr Han – are painfully torn between protecting themselves and wanting to reveal their desire for each other. The performances are uniformly brilliant, where deep emotion is expressed through hurt and restrained performances.

Meanwhile, Lim Ok-hee often acts as an intermediary between the two adult characters. Jeon yeong-seon who plays Lim Ok-hee produces one of the most brilliant performance in South Korean film. She carries a film of immense dramatic weight on her shoulders with ease whilst managing to be funny, charming and three-dimensional, particularly in her scenes with Mr Han. Despite this, these sequences can be equally crushing. Shin Sang-ok cuts from touching moments of the pair together to the opinions of other characters. Reminding the audience that this chance of a fatherly relationship may never be attainable for Lim Ok-hee, especially if society continues to enforce their judgements upon her mother.

Frustratingly, The Houseguest and My Mother was needlessly remade in 2007, but like many remakes it fails to capture to the true power, or even the tone, of the original. The 1961 version possess an intangible quality that simply cannot be replicated. It has to be seen to believe just how moving it is.

9. No Regret (Leesong Hee-il, 2006)

With No Regret, Leesong Hee-il has created one of the finest LGBTQIA+ films of the 2000s. One of the first openly gay South Korean directors, Hee-il crafts a complex, powerful story that will easily translate across different nations and sexualities.

No Regret exists in a Korea where success, be it personal or financial, is out of reach for our characters. Lee Su-min is an orphan who out of desperation becomes a male escort. Lee Yeong-hun’s performance as Su-min is in turns dangerous and confrontational. He lives in a world where love appears non-existent and sex is a purely transactional exercise. The audience may not agree with every decision Su-min makes but still empathise with him as the director Hee-il crafts a world where Su-min has little to no other option.

Conversely, Song Jae-min is a businessman destined to work in his family’s business against his will. Most pointedly, he has to wed a woman he has no interest in. In one of the most poignant sequences, Song Jae-min reveals his sexuality to his wife in front of all of his family. The group are trapped in an elevator and the tension is palpable. Director Hee-il leaves his characters with nowhere to go and forces both the characters, and his audience, to face the reality of their situation.

Moreover, the cinematography reflects the characters’ doomed state of affairs. Director of Photography Yun Ji-woon provides No Regret with a digital look, creating a rugged but intimate home movie feel – perfectly suiting its characters. Often the city lights and skyscrapers of Seoul linger in the background of shots as our characters sit on the floor. As if the power structures of the world they inhabit constantly loom over them. Their exclusion from the world evident.

In fine, Leesong Hee-il paces his film effectively and builds the story to a devastating climax. One that, in hindsight, feels inevitable but when initially viewing the film is entirely shocking. Truly strong work.

10. Bedevilled (Jang Cheol-soo, 2010)

Perhaps the toughest watch on the list. Bedevilled is a violent, shocking film that neatly defies any genre you place it in. A horrific film, yet to call it a horror or even a thriller feels too simplistic. Bedevilled is an stirring cinematic experience but one that can be punishing to sit through.

The film follows Hae-won a woman recently suspended from her job. In a moment of both personal and professional crisis, she decides to return to the island where she was raised. On this island, she reconnects with Kim Bok-nam – a woman subject to emotional, physical and sexual torment until she inevitably snaps.

Like all great works of tension, Bedevilled is so uncomfortable because it is rooted in reality. Jang Cheol-soo, creates a dread that is very real on screen. Here, the terror present is the threat women face from men. The male characters of Bedevilled are terrifying: they loiter in the frame, commit horrific acts of violence and are morally reprehensible. The audience is never allowed to relax when men are present on screen – anticipating the worst.

While lesser directors would have delved into schlocky exploitation, Cheol-soo avoids this. His focus is on the impact of violence on his characters – how it damages them and leads to a cycle of violence and abuse. Cheol-soo presents the abuse in unrelenting close ups – forcing the audience to watch the atrocities being committed. Likewise, once Kim Bok-nam begins here own spring of vengeance, he presents the violence in a near mirrored style.

Yet, no enjoyment comes from the vengeance. Jang Cheol-soo uses violence in his film for a purpose. It highlights how damaged Bok-nam has become. After the grisly killing of one of her abusers, the director lingers on Bok-nam crying over the body – the effect of the abuse still very present within her. The confidence of a director to tackle this kind of subject matter for their debut film, with this level of confidence, is nothing short of astounding. Ultimately, whilst not necessarily pleasurable viewing – Bedevilled is one impressive watch.