Films that celebrate youth are beloved by audiences and directors alike, explaining why the genre has new entries every year. Those worthy of our time are like a looking glass that one watches but also steps through, rediscovering a part of our former selves previously lost to the dark waters of the unconscious. This nostalgic allure of films that choose youth as their subject, whether in the acme of its frivolity or on the inevitable descent towards adulthood, document a social reality that would otherwise exist only as a faded memory, as fleeting as a lucid dream at the moment of waking up.

When one thinks of youth there are some obvious things the come to mind: music, first loves, rebellion, sex, cars, the first tastes of independence, doubt, chance, among many others. Each of the following films documents these elements of growing up to varying degrees. There are similarities in production values among some films, while others share approaches to the cinematography, scenario, or script. Some even explicitly acknowledge one another. In a collection of those films that encapsulate the best of the genre, a group of agreed-upon forms emerges that belong to the language, experience, and memory of one’s most transient years.

1. American Graffiti (1973)

Arguably the film that created the blueprint for the hang-out movie, George Lucas’s American Graffiti embodies many of the tropes also now associated with the coming of age genre. There is barely any plot to speak of, the characters have a liberating listlessness about them, and more attention is paid to those icons of adolescent freedom, such as the school dance, cold shakes at the diner, and the red flashes of taillights, than to any exploration of character or plot. As languid as a school day spent dreaming of elusive adulthood, the pacing is also not in a hurry.

Part of the hang out movie’s charm is the luxury of not being in a rush. Admiration and nostalgia of the character’s surroundings affect every shot. The camera cannot resist capturing another hotrod roaring past a colorfully blinking advertisement, dwelling on its neon lights like a last goodbye. While some may perceive this film as obvious and a zoetrope of clichés, others may even say banal, it has an undercurrent of melancholy for days gone by. This sentiment universalizes the film, which is why nearly fifty years on comparable films still draw inspiration from it (compare Once Upon a Time in Hollywood), and why it is essential viewing.

2. American Honey (2016)

Fraying on the edge of Middle-America, Star is a young woman who encounters an alluring young man named Jake who invites her to join his cohort of outsiders. In search of an escape more than capital gain, she accepts his dubious offer, taking chance after chance as they freewheel across the American landscape, mesmerized with one another and enamored in their social anarchy, silently knowing it is only a moment in time like their fleeting youth.

As long as the summer solstice, American Honey could not say what it needs to say without its 163-minute duration. There is a repetition of imagery in the film, whether of a horsefly imprisoned behind a windowpane, or birds freely flying as an expansive azure sky glows in the background. Repetition queues a rhythm that forms a constellation to Star’s pattern of emotion and thought. These perspective shots of how she sees the world are also how she understands her position in it. This cyclical structure of the film is the essence of its dramaturgy. More than any other fond, teary-eyed glimpse at youth, American Honey has a metaphysical bent to its perspective.

3. Beautiful Girls (1996)

As the title suggests, the central conflict of Beautiful Girls is how its male characters assess beauty. This conflict plays out in their nostalgia for superficial adolescent notions of what constitutes a beautiful woman, and their struggle to adapt to mature adulthood romances because they bear little resemblance to their childhood fantasies.

Nostalgia is a fundamental emotion of the film that is built into its premise. The plot starts as Willie returns from New York to his small-town Massachusetts home for a high school reunion, reconnecting with other friends who also left and some who never did. Before the characters reveal how they are still holding onto some of their teenage neuroticisms, there is already a sense of journeying down memory lane and not being ready to cut ties completely with the past. At one point, Paul describes their hometown as stagnate, “things around here never change,” which functions as an insight that characterizes the dilemma of letting go of one’s youth. It’s this willingness to accept change, especially when it is not how the characters envisioned, that they grapple with throughout the film.

Paul’s character is the most buffoonish of these, as he fumbles his way through a disingenuous attempt to win his long-time girlfriend back, only to contrive a fake scenario to make her jealous after she rejects him. His corrosive behavior reaches its pinnacle when he decorates his living room walls with magazine cut-outs of half-naked supermodels. He then delivers an ironic speech that envisions these fabricated images of manufactured beauty as totems promising freedom if only they could be possessed. Little does Paul realize that his antiquated perceptions of women and sexuality as objects imprisons him from evolving to meet the needs and demands of a mature relationship, capable of love.

In a similar, yet juxtaposing dilemma, Willie develops a Platonic relationship with 13-year-old Marty. He confesses to her his doubts about whether he loves his girlfriend and whether he should continue his passion for working as a struggling pianist, taking a sales job instead. Under the grinding wheel of New York City, Willie develops a callous outlook that Marty assuages through her innocent perspective. She is a vestige that gives Willie the nostalgia he is seeking, restoring his belief in possibility and determination that the banal necessities of survival were crushing.

4. The Dreamers (2003)

For those who are yet to see Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, be sure to round out your silent era, classic Hollywood, and 1950s French arthouse backlog. It parallels the lives of its characters with footage from some of film history’s most dramatic moments, giving away their endings. This intertextual device is charming in its homage, but it also effectively closes the separation between reality and film, framing how and why the characters play out their wildest imaginings.

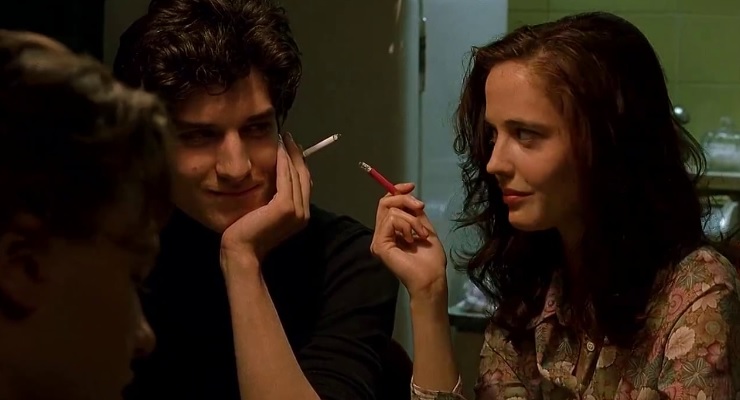

Matthew is a 20 year old American living in Paris in 1968 when he meets a sister and brother, Isabelle and Théo, at the famous Cinémathèque Française, quickly enfolding himself in a love triangle with the pair. Bonding over their love of cinema, they reenact their favorite scenes and reference esoteric allusions that the other has to guess correctly, or forfeit to the other’s request. This actor-director dynamic pushes the boundaries of self-discovery to the extent of dissolving the distinctions between family, friendship, and love. As Matthew learns more details about Isabelle, he realizes the depth of the brother and sister’s illusory mediated existence.

When a protest breaks out in the film’s final sequence, Isabelle and Théo confuse anarchism with social justice, leaving Matthew behind, perplexed at how the risks and dangers of reality never penetrate their fantasies and idealism. For a film that opens with a wondrous mood, it ends on a rebellious, yet cautionary note on the dangerous power of cinema.

5. Ghost World (2001)

Two cynical high school graduates wander the glossy consumer branded, yet eerily empty streets of their unidentified suburban town, visiting record shops and diners where they criticize the stupidity of others while enveloped in a malaise of indifference about their futures. They plan to move in together, so Rebecca makes the obvious move of the underachiever and scores a job as a barista.

After seeing an advertisement in the newspaper from a middle-aged man named Seymour looking to reconnect with a woman he had a brief encounter with, Enid arranges a fake blind date, where she and Rebecca observe him from a distance, cruelly laughing at Seymour’s expense. Enid crosses paths with Seymour again at a garage flea market where she learns that he is a huge music nerd. As someone who feels misunderstood because of her niche curiosities, Enid takes a greater interest in Seymour than the banality of finding a job and a new apartment.

Ghost World has melancholic humor that summons that elusive belly laughter few films have the power to muster. It has an ambivalent ending that resists being easily understood like the main protagonist, Enid. On a superficial level, she’s pretty unlikable – many self-absorbed teenagers are – and yet Seymour, who is a more modest older variation of the idiosyncratic intellectual Enid identifies as, forgives her adolescent shortcomings and sees the beauty of her potential.

Icons of American consumerism, such as the McDonald’s and Radioshack logos, that color the background are so out of sync with Enid’s own aesthetic and attitude, they turn her into a walking anachronism. Similar to the love-hate relationship the film inspires among its viewers, Enid is a paradox. She knows the disappointment she causes in others but is unable to be anything other than true to her unclarified self.