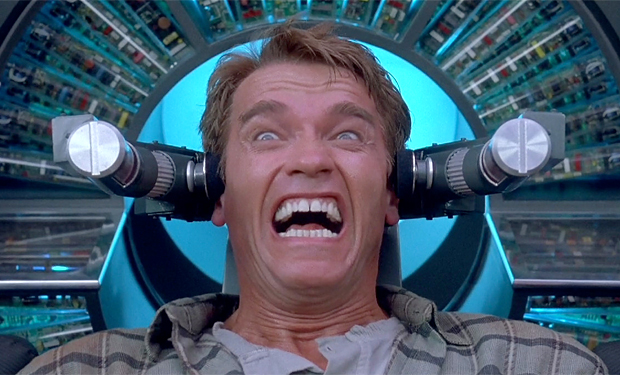

5. Total Recall

The second Paul Verhoeven picture to make our list of technophobic cinema, Total Recall focuses on the experiential element of a digitized society. The characters live inside a synthetic world manifested through implanted memories, creating the remarkable illusion of stories and relationships that never occurred, an endeavor designed to break the grueling monotony of working life.

The question remains: do we fit that description as well? Almost as if the film predicted Facebook’s dominance over the way millions spend their time, the satirical action picture asks us to consider which life we value: the messy satisfaction of real existence or the filtered image we project online?

Though Verhoeven texturizes his movie with philosophical queries regarding how we think and behave, Total Recall never veers into a quiet or meditative zone. Instead, the story moves at whiplash-inducing speed, delivering some of the most memorable sci-fi iconography of the late eighties/early nineties. Triple-breasted exotic dancers, baby-sized revolutionaries who reside inside a man’s chest cavity, Governor Schwarzenegger chucking an exploding costume head at his enemies—such visual yumminess reminds us of why we love these films even more than their directors hate technology.

4. Moon

From the Cro-Magnon Man’s first wheel to AI-powered personal assistants, we always develop technology with the goal to replace some part of ourselves. The printing press, the automobile, the smartphone—all of those doodads streamline a more painstaking human action with a faster finish time. What happens when the progress goes beyond its intended function? What befalls us when some machine decides, instead of providing a surrogate for human work, to take the place of an entire person, mind, body, and all? Moon answers that question.

Back on Earth, energy supplies run low, so NASA sends an astronaut miner to a moonbase to harvest a precious gas that reverses the crisis. He spends three years on that rock, with only a robot as a companion, a situation that makes him yearn for his wife and child back home. With this narrative setup, the audience considers the isolation created through technology, how the devices designed to connect us end up causing the opposite effect. When the question of human autonomy factors into the equation, then Moon becomes a dark exploration of the malevolent role technology plays in our lives.

3. Metropolis

The oldest and most influential film appearing on this list, Metropolis set the standard for which most every technophobic movie strives. The silent picture not only inspired the look of cinematic icons such as the cowardly gold robot C-3PO from Star Wars, but it also delivered a terrifying glimpse into a world ruled by machines. To this end, it leans on a very pointed social element, focusing much of its imagery and narrative on the plight of the proletariat whose efforts fund the well-to-do’s lavish lifestyles.

As the colossal gap between the rich and working classes grows ever wider, the question about technology’s role in creating the economic chasm remains. The screenplay explores how, even though machines wield the power to shorten workdays, the bourgeoisie uses them only to create obscene financial gain (instead of making life easier for the worker). In the end, the wealthy elite fails to realize that these robotic tools feel only ambivalence toward the haves and the have-nots alike.

2. Blade Runner

As it grows more intelligent and invasive, technology’s progress hinges not so much on replacement of the outdated so much as a rebirth of what already exists. In other words, as long as their evolution stays in this state of perpetual movement, here the machines shall remain. Which brings us to a hard-to-swallow, unblinking truth: our gadgets own us through a sort of tractor beam, an irresistible pull that beckons us down a never-ending digital rabbithole. We scroll our social media feeds, judge our neighbors, covet someone’s life, ogle another person’s physical allure, and feel sad in light of what the universe neglected to give us.

These days, we use technological platforms to create a new version of ourselves, hoping to create envy more than that which we already feel. Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner takes this habit to a literal level, telling the tale of replicants who move from a digital space to a literal one. Unlike the more elegant facades we engineer on Facebook, these clones exist to serve a purpose, live a few years, and perish. Once the replicants fight for their lives, the police state hunts them down. The clones become too human and not enough machine, so according to humanity, they need to disappear. They need to get lost in time like tears in rain.

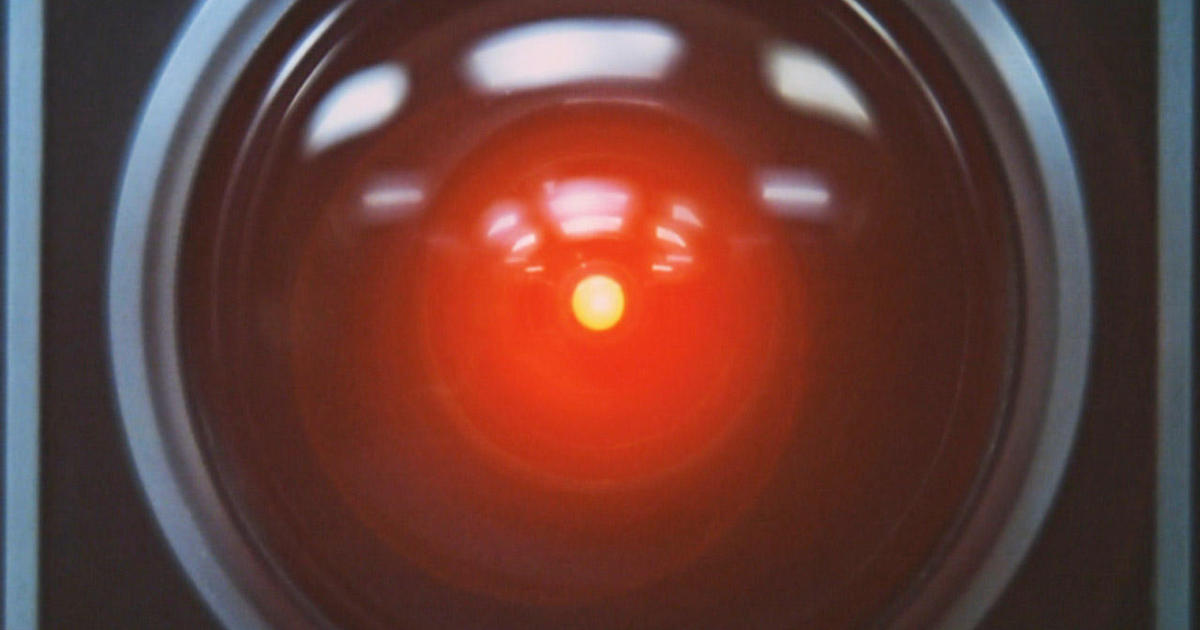

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Bookended by two twenty-something minute intervals of meaningful silence, Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece demands that the audience contemplate the messy path of human progress. From the crude bone tools simians use to space vessels that orbit Jupiter, technology delivers the fuel required to propel society forward. But at what cost? The film explores multiple dimensions of the human psyche, but the most memorable conflict centers on the astronaut Dr. Dave Bowman and the homicidal supercomputer HAL 9000. As the red-eyed machine kills one person after the next, it remains calm and methodical, showing how taking so many lives amounts to a humdrum activity.

This interstellar bloodbath epitomizes the way we mislabel progress. Though some gadgetry assists with medical operations, and other telecom devices allow us to see those we care about from great distances, other machinery spoils the environment and seeks to change our behavior for the worst. Learning a song at first and then discovering how to stop a heartbeat, HAL 9000 embodies that dystopian vision of technology that grows so smart, it stops assisting and starts assassinating.

Author Bio: John Stanford Owen received his MFA from Southern Illinois University, where he also taught English courses. When not penning reviews and essays on cinema, JSO reads and writes poetry, takes walks with his wife and dog, and dances to Radiohead. Connect with him on Twitter @jstanfordowen.