Saturday, June 28, 1969. We’re at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village.

It’s 1:19 a.m. in the dark nightclub.

The walls are painted black and the only lights that are on are pulsating gel ones.

It’s 1:20 a.m. and a total of eight police officers burst in through the double doors and shout: “Police! We’re taking the place!” Normally police raids, which have become a routine occurrence at this time, were always tipped off beforehand, especially considering that the club is owned by the Genovese crime family. It’s the only bar for gay men in New York City where dancing is allowed.

The lights go on and the music stops – as per usual. 205 people are in the bar.

The raid does not go according to plan. The men refuse to show their identifications for yet another time, and the police start carting everyone off. The crowd outside grows larger and larger, congregating to find out what the police cars are doing there.

And soon, it’s a revolution.

Soon the screams of gay liberation spread. Violence ensues. And a lot more happens.

Led by Marsha P. Johnson and other rebels who made a large dent in the monotonous destruction of homophobia, this was the beginning of the Stonewall Riots. Perhaps the most important even leading to the gay liberation movement and the ever-going fight for LGBTQ+ rights around the world.

In celebration of Pride Month, we are looking back at all the beautiful queer films to have graced our screens. But first, an extracted letter from the Gay Times editor, William J. Connelly, from their own 2018 Pride issue;

“Pride: a feeling of deep pleasure or satisfaction derived from one’s own achievements, the achievements of one’s community, or from qualities or possessions that are widely admired… The grit and determination of queer people around the world is directly responsible for the freedoms that many of us now enjoy.

While we take a step back to celebrate all that we as a community have achieved over the years, it’s vital that we reflect upon the work that is still left to do. In 71 countries around the world it’s still illegal to be gay and in the UK, LGBTQ people are four times as likely to commit suicide as their straight peers, while 50% of trans people here have attempted to end their lives. These figures should not only frighten us, but rally us together once again.”

Representation is important. Representation of something that has been purposely sanctioned and silenced for so long, is even more so. Fortunately, more and more films are being made that depict the spectrum of queer experience. Showing the public (gay, straight, and everyone in between) the feelings, emotions, and personal accounts of life that many people have never interacted with is crucial for creating a more united world.

Normalising these experiences effect the perception others have of such orientations, but perhaps more importantly, effects the way these LGBTQ¬+ people view themselves. Queer individuals are finally in a position where they have the potential to identify with mediated characters on-screen.

So, in order to celebrate all of this and all those people who worked for queer representation in cinema, here are twenty-five of the most beautiful LGBTQ+ films. Remember, this is not an exhaustive list and there are plenty more queer films to see. For the subject being taboo and absent from cinema for so long, it’s time to start making up for all the lost stories we could’ve had.

(This list is long. Grab a meal.)

1. Paris Is Burning (1990) dir. Jennie Livingston

A quintessential masterclass in the extremely influential drag ball circuit of 1987 Harlem, Jennie Livingston’s raw documentary Paris is Burning captures the bugle beads, the rhinestones and the epic fantasies these queens create despite the constant fear of homophobic harassment that has often quickly escalated to the loss of lives.

As Dorian Corey says while putting on her make-up in a small, magnifying retractable mirror, feather boas framing her cramped set-up: “In a ballroom you can be anything you want”. Indeed, in a world where being who you are is seen as the devil incarnate, finding solace in escaping into an alternate reality where you can be as fierce as possible and have people worship you, is a fantastical marvel. Audiences screaming, snapping, gagging on eleganza while the queens twist and twirl in the ‘realest’ couture.

“It’s like crossing into the looking glass in wonderland. You go in there, and you feel- you feel a hundred percent right- of being gay. And that’s not what it’s like in the world. And you know, it should be like that in the world.”

But the goal is not only to become legendary, it is to feel that sense of belonging that so many LGBTQ+ people lack. So many people face shame, embarrassment and excommunication; being rejected by their families and homes based on their orientation, that they seek to form their own families- drag families.

Livingston interviews several mothers and members of these iconic ‘houses’; Pepper LaBeija, Kim Pendavis, Venus and Angie Xtravaganza, Will Ninja, Dorian Corey, and Octavia Saint Laurent, who all reminisce and explain the urban New York queer scene. But what exactly is a ball? As Corey puts it, a bunch of gay men gather under one roof and decide to have a competition amongst themselves. They walk the runway according to different ‘categories’, get judged, and win trophies for their Houses. A place where these hushed voices who can’t find their place in straight, white reality, finally get the chance to live their fantasies of being superstars.

Seeking opulence in terms of fame and success. Most categories rely on being ‘real’, i.e. being able to blend into the heteronormative world. The working title for the film was in fact “To Be Real”, paying reference to Cheryl Lynn’s disco hit “Got to be Real”- a song which is heavily utilised in the film. Together with a deep description of drag life, the queens also speak openly about transsexualism and their issues living life as a woman in a hate-filled, dangerous world.

“When they’re undetectable, when they can walk out of that ballroom, into the sunlight and onto the subway and get home and still have all their clothes, and no blood running off their bodies – those are the femme realness queens.” ¬

Discovering the origins of shade, reading, and vogueing, this Sundance Grand Jury Prize winning documentary serve as a primary source for recent, successful television shows which also explore the drag ball circuit, like Rupaul’s Drag Race (2009-) or Ryan Murphy’s Pose (2018-).

Ninja speaks about the influences of vogoeing, the dance denominated after the fashion magazine also finds its roots from Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics (which links in to the mysterious Egyptian head busts in the background of different queens’ talking head interviews), and some forms of gymnastics. The ambition of striving for perfect lines in form and experimenting with awkward positions is a strong trait which is shared with Classical aspirations.

The iconic grainy doc is currently available on Netflix.

(Bonus: A fantastic precursor to this film is Frank Simon’s The Queen (1968), which follows the events of the 1967 Miss All America Camp Beauty Contest in NYC. Featuring the queen and founder of the legendary House of LaBeija: Crystal, epically sulk and shade).

2. Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins

“I cry so much sometimes I think one day I’m gone just turn into drops.”

Based on Tarell Alvin McCraney’s semi-autobiographical unproduced play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue”, this coming-of-age story has single-handedly shifted African-American queer cinema into the mainstream. Interestingly enough, Both Barry Jenkins and author McCraney had congruent visions for the film since both men grew up in the same poverty-stricken Liberty City neighbourhood of Miami.

Both men also have mothers who struggled with drug addiction. A masterpiece in storytelling, the film is divided in three succinct parts; i. Little / ii. Chiron / iii. Black – based on the similarly structured Hsiao-Hsien Hou’s Taiwanese film “Three Times” (2005). Each section roughly translates into snapshots of our protagonist Chiron’s evolving life, with Little representing his childhood, Chiron his adolescence and Black his adulthood.

We first meet Juan (Mahershala Ali), a Cuban drug dealer who finds a little, withdrawn boy in a dilapidated crackhouse where he was hiding from bullies. He takes him home for the night and introduces him to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

Boy: “My name is Chiron. But people call me Little.”

Teresa: “I’m gonna call you by your name.”

When Juan takes Little (the tremendously sad-eyed Alex Hibbert) back to his house, we discover that his mother Paula (the extremely talented Naomie Harris) is a drug-addict. Little and Juan continue to spend time with each other, with Juan becoming a pseudo-father figure to him. In one particularly beautiful sequence, Juan teaches him how to swim. The lens bobbing along in the ocean, partially submerged within the water, learning along with Little.

This film is all about names, particularly the concept of given names. Juan relates a story of an old woman back in Cuba who told him, “In the moonlight, black boys look blue. You blue. That’s what I’m gonna call you: Blue.” Confused, Little responds, “So your name Blue?” Juan chuckles and speaks this little treasure of a line that is absent from the original screenplay and which also formulates the reasoning behind the title names: “Nah. At some point, you have to decide for yourself who you’re gonna be. Can’t let nobody make that decision for you.” With a childhood full of derogatory terms being shouted at him and people refusing to call him what he wants- this is vital information.

Cut to when Little is being gang-tackled by a bunch of mean boys. He is saved by who looks to be his only similarly-aged friend in the film: Kevin (Jaden Piner). Kevin tells Little that he has to learn how to fight and not to be “soft”. The two play-fight in practice. Barry Jenkins describes it in his script as:

“This is anthropology, anatomical vignettes, the struggle of these two boys isolated to the simple, incomplete movements of partially glimpsed bodies. These are children. Sexuality is absent (from) these images and yet, the hints of something sensual, fleeting in its appearances; Kevin’s cheek wedged close to Little’s neck, blades of grass sticking to their skin… Kevin looking back at Little, looking down at him lying there, Little fully returning his gaze, these fourteen pages the first time he’s looked at anyone thus (far).”

Cut to ii. Chiron (Ashton Sanders), where he’s now insisting that everyone calls him by his actual name. But the bullies still call him ‘little’ and ‘faggot’, the same as they horridly did in part one. Kevin (Jharrel Jerome) now relates stories to “Black” – his new nickname for Chiron – about some chick fellating him. These stories go on to haunt Chiron’s subconscious. He goes to the moonlit beach, where the ocean whispers loops around him, that is; until Kevin turns up.

Perhaps the most noteworthy scene in this film is the impromptu sequence in which Paula soundlessly screams at Little (or more accurately: us, since she’s staring straight into the camera) in slow motion. Purple neon highlighting one half of her face, like the moon. This singular scene re-emerges later in the film with sound, over-cranked at the high frame rate of 48fps, terrifying Black (Trevente Rhodes) and waking him up from his dream. Made even more impressive by the fact that all of Naomie Harris’ scenes had to be shot within three days due to Visa issues and Spectre press tours.

Jenkins has said multiple times in interviews that he is a massive fan of Wong-Kar Wai, and paid respect to the listed “Happy Together” by using the film’s featured song “Cucurracucú Paloma”, in his own work to reflect the thematic similarities between the films. Music is important in this film. Mainly because it is just so good, and because in act three- a certain jukebox playing Barbara Lewis’ “Hello Stranger” says everything our characters simply can’t. As Jenkins says in his screenplay:

“… ‘Ooh, it seems like a mighty long time.’ It’s on the nose, yes, but fuck it: reminded him, like a punch flush to the face, forever and always a reminder of this thing, of everything.”

Nicholas Britell who curated perfect old-school “chopped and screwed” rhythms to perfectly mix in with his own instrumental score for the film. Chiron’s thematic melody gets darker and deeper as the film progresses, effortlessly reflecting his coming-of-age and inner struggles. My personal favourite out of the score is the epically beautiful “The Middle of the World,” which has strings so tense that you can feel one of them about to snap. The theme also sounds vaguely reminiscent from Oldboy’s (2003) 28-second piece “Point Blank”.

With its Truffaut ending, the film scored big at the mainstream film award circuit, taking home Oscars for Best Supporting Actor (Ali), Best Adapted Screenplay (Jenkins & McCraney) and Best Picture, being the lowest budget movie to ever win this award.

3. Happy Together (1997) dir. Wong Kar-wai

May, 1995; Ho Po-wing (Leslie Cheung) is stretched out across the bed, smoking a cigarette and leaning over to the bed-side table clad with a cigarette graveyard for an ashtray, some poloroids of the couple and a cylindrical lamp portraying the Argentenian Iguaza waterfalls.

When the lamp is on, it looks like the waterfalls are running, twinkling with small shining lights. Across the cheap, borderline-disintegrating room is Lai Yiu-fai (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), or at least the dirtily crusted partial reflection of him in the mirror, barely dressed in a pair of tighty-whities. He initially buries his face in the crook of his arm, hiding from his partner until Po-wing says; “Let’s start over.”

Wong Kar-wai’s romantic drama “Happy Together” (Chun gwong cha sat) takes its English name from The Turtles’ 1967 psychedelic pop hit single, a song which is covered by Danny Chang in the film’s credit sequence. The Chinese title refers to an idiom “‘Spring Light Bursts Forth’, connotating the revelation of something indecent” and was purposely lifted from the Hong Kong release title for Michelangelo Antonini’s 1966 mystery-thriller Blow-up.

Cut to the intertwined couple making out in their underwear on one of two single beds in the small room. Lai’s voice over informs us that Ho always says this, and that every time- it gets to him. The couple’s tumultuous relationship is characterised by an abusive, destructive pattern; often leading to fights, arguments and subsequent break-ups until- they “start over”. This time, they’re leaving their home in pre-Handover Hong Kong and land in Argentina.

Of course, soon after, Lai gets broken up with again, being told he’s boring to be around. leading to him trying to find work in Buenos Aires to support himself there and get enough money to fly back to Hong Kong- alone.

Soon enough, Ho turns up at Lai’s door, severely beaten up with unusable hands; broken, destructed and in desperate need of his help. Lai cautiously takes him in, careful not to repeat their patterns over again and keep the ‘friendship’ platonic. Lai feeds him, clothes him, cleans him, and lets him sleep on his bed (he courteously and very self-projectingly takes the sofa, although that does not stop Ho from trying to sleep with him).

Kar-wai’s signature editing, step-printing, elliptical uses of both slow-motion and fast-motion, as well as Godard-inspired jump cuts intensify the simple transactions between the characters to show what is going on in their minds. So, something like the two of them sharing a cigarette is slowed down to highlight every emotion that flickers across their face, every puff of beautiful smoke that drifts into the air behind them, and their ever-growing romantic sexual tension building underneath their cool, hard surfaces- which inevitably break down into tears.

Together with this, the film flickers between new wave black-and-white to overly saturated colour, with intense yellows beaming from the Argentinian sunlight, concentrates reds and greens, exposed lightbulbs to faded 35mm bluish waterfalls, all sewn together by punctuating uses of Astor Piazzolla’s Tango Apasionado (another signature of Kar-wai, that is; repeated uses of the same song which soon becomes its own anthem to the film), and some zingy Zappa. The film was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival, where Kar-wai also won Best Director.

Literary References:

– Tony Raynes. In the Mood for Love: BFI Film Classics (2015).

4. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

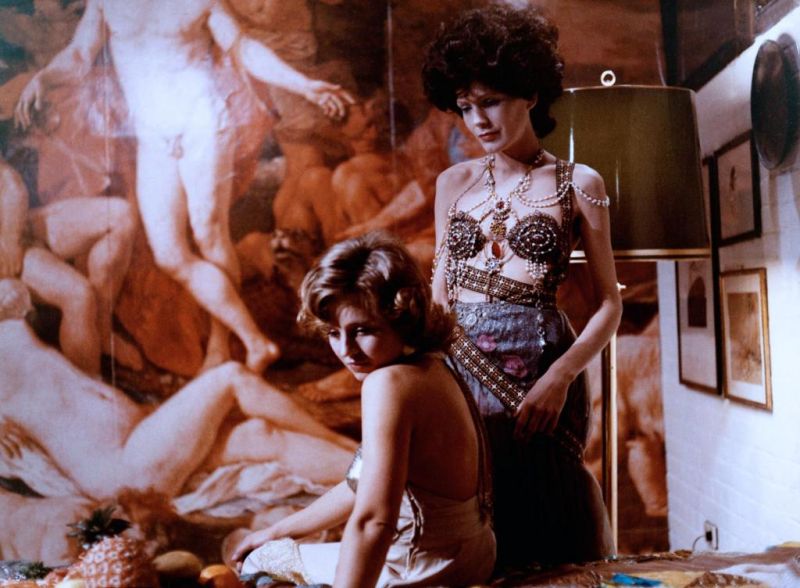

A room is decorated with (1) a giant wall-sized reproduction of Poussin’s Midas and Bacchus, (2) an ever-increasing number of female mannequins whose faces are laid for the gods, (3) a bed which is constantly laid upon by our effortlessly chic and arrogant protagonist, Petra (Margit Carstensen), (4) an easel with a mountedcanvas that is continuously worked upon by Petra’s mute, obedient servant, Marlene (Irm Hermann), (5) a turn-table with a nearby bowl full of records. This is the entire set of Fassbinder’s femme-driven West German film Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant.

Petra, who may not be the most relateble of lesbian characters but is suredly one of, if not the, most confident characters in queer cinema. Well, at least at first and in her own safe space. But soon enough, she slowly falls apart as her married, bisexual love interest Karin (Hanna Schygulla) growing incompatibility becomes clearer and clearer.

The decision to use Poussin’s Midas and Bacchus (c.1629-30) in particular is no accident. The oil painting depicts the Greek legend Mildas, who was granted a wish by Bacchus (the god of wine, literally) for a good deed he had done. Of course, we know the mythical rule that wishes always come at a cost (thanks Aladdin) and Mildas’ wish to have everything he touched turn to gold soon turned sour when all food became inedible.

A myth that tells us be careful what we wish for, but also warns against greed, hedonistic appetite and insatiable sybaritic luxury; all of which Petra von Kant indulges in. Dripping in jewels, her sparkling fringe silk robe lined with puffy white fur swivels as she slow dances with Marlene. Her uniquely designed blue tulle dress, wrapped in belt-like ribbons (or ribbon-like belts) and pearls circling her breasts as she lies in bed drinking with Karin. Both looking like reborn fashionista gladiators. Red wigs, brunette wigs, blonde- all covering her true auburn hair for the many visitors she receives in her apartment.

Completely void of male presence (unless you count Fassbinder’s cameo as the man in the newspaper photograph with Petra and Karin), the film remains a landmark in lesbian cinema. Single camera shots that effortlessly achieve a depth of field within the room, and are themselves framed like a painting- with limbs being carefully choreographed into screen-filling positions that never disrupt long takes.

The film itself was shot in 10 days with the script being entirely written during a twelve-hour long-haul flight from Berlin to Los Angeles, based on a previous play made by Fassbinder himself. The melodrama pays respect to George Cukor’s “The Women” (1939), an all-female comedy-drama that similarly takes place in the glamourous Manhattan apartments of high society.

(Bonus: Fassbinder also director gay-themed “Fox and His Friends” (1975; also known as Fist-Right of Freedom), starring himself as the queer Fox).

5. My Own Private Idaho (1991) dir. Gus Van Sant

A close-up of a dictionary entry:

narcoˑlepˑsy: a condition characterised by brief attacks of deep sleep.

Cut to a blue screen with a white ‘Idaho’ superimposed in the middle of it.

A road now. With a still beautifully alive River Phoenix on the side of it. He’s got a dented forehead with a confused expression, a duffle bag and a gas station shirt with the name Bob stitched on to it.

“There’s not another road anywhere that looks like this road. I mean, exactly like this road. It’s a one of a kind place. One of a kind. Like someone’s face. Like a fucked-up face.”

The concept of finding beauty in the uniqueness of things begins and he falls asleep at the drop of a hat. This is Gus Van Sant’s 1991 indie classic “My Own Private Idaho”, his third feature and follow-up to his 1989 break-through “Drugstore Cowboy”. Paying extended homage to Orson Welles’ adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays, “Chimes at Midnight” (1965), the film focuses on the friendship between the dreamy, narcoleptic Mikey Waters (River Phoenix) and the rebellious, libidinal Scott (Keanu Reeves), two young street hustlers on a road trip to find the “myth of maternal love”.

The two of them sleep with whoever pays them; whether it be an extremely odd, germaphobic man with a love for ASMR induced by cacophonic scrubbing sounds, or a three-guy-needing, rich fur-lined-robe-wearing older woman (the amazing Grace Zabriskie) who subconsciously triggers Mike about his abandoned mother. But while Scott claims only to be gay for pay, Mike longs for romance with his best friend.

The two do drugs and squat at an abandoned, dilapidated building hosted by Bob (William Richert) with his group of social outcasts. Scott makes overtly sexual advances on Mike, not out of any true attraction, just in the punk effort to make straight people (and his rich father) as uncomfortable as possible.

One of the most notorious scenes, commonly referred to simply as the campfire scene, is perhaps one of the most heart-breaking and relatable scenes for anyone who has ever experienced unrequited love. At the half-way marker of the film, the two camp somewhere in a field in the potato state of Idaho.

The thematic use of orange throughout the film (most walls are red-toned, most of Mike’s clothes are orange) seemingly come to a culmination in this sequence, with burning rust tones sparking between the two whose spark is undermined by mismatched orientation. Heavily improvised and in fact mostly written by Phoenix himself, the intense scene of truth was the last to be shot at Phoenix’s personal request- helping it achieve its emotional climactic feel.

Todd Haynes (a.k.a. New Queer Cinema icon) told The Criterion Collection that “Before the (campfire) scene, it’s almost like the kids are all victims of homosexuality. There’s a scene where they all sit around telling their stories of being raped and abused. It’s not until River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves sit around the camp fire, that you see one of the hustlers being gay in an all-natural environment, with no money exchanging hands.” Indeed, the representation of all things queer vary on the spectrum from practicality to heart-wrenching affection.

Scott: “Two guys can’t love each other.”

Mike, trying instead to focus on the small fire-lit branches to occupy his both his hands and mind, noncommittally agrees but immediately negates himself. With his head buried into himself, his arms wrapped around his bent knees, Mike is basically a freestanding foetal position (in keeping with the maternal theme). Vulnerable to the world with what he is about to say, he speaks lowly, quietly and timidly: “Well, I… I don’t know. I mean… I mean, for me… I could love someone even if I… you know, wasn’t paid for it…” Special attention given to the genderless ‘someone’.

Nominated for the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion and winning the Volpi Cup for Best Actor (Phoneix), this grunge film punctuated by super 8 family footage and one-off characters speaking about their aspirations and queer experiences, remains one of the most tender and profound films of New Queer Cinema, and of Van Sant’s filmography.

The blending of isolated country houses that look like they’ve been taken out of romantic English landscape paintings (hey, John Constable), the “self-consciously anachronistic use of Bardspeak” and the angelic sounds of Mike’s nocturnal breathing make this film a one of a kind. You know, like a fucked-up face.

Literary References:

– Steven Jay Schneider, 1001 Movies to See Before You Die (2014).

6. My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) dir. Stephen Frears

Battersea, South London: We follow Omar (Gordon Warnecke), a British Pakistani trying to make a name for himself and achieve business success. His entrepreneur Uncle Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey) offers him an opportunity to transform and manage a run-down laundrette.

He also finds work delivering drugs for his cousin, Salim (Derrick Branche), who he’s currently in the middle of driving home until: their car gets viciously attacked by a gang of neo-nazi-esque, extreme right wing street punks who zoom in on the fact that they’re not white. But the only thing that Omar can see is Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) standing across the road. His hands are in his pockets, his jaw is clenched, his brow convoluted, and his spiky bleached blond quiff sticks upwards from his dark roots and humble flatcap – Johnny is way too cool for school.

Despite just being attacked for the colour of his skin, Omar beams as he purposely walks over to the subversive, street-side punk. Music builds as Omar sashays with a glowing smile and tenderly languishing eyes.

Omar: “It’s me!”

Initially confused, Johnny brushes off Omar’s adorable enthusiasm, avoiding eye contact while simultaneously burying a smile under his cool expression.

Johnny: “I know who it is.”

The two catch up. They’re been childhood friends since they’ve been five, but the two haven’t seen each other for a while. The gang members encircle them in the shadows- but it’s not a follow-up assault- it’s just pure confusion at why their friend is talking to a Pakistani. Omar completely ignores them, and what their presence infers what Johnny’s current political and racial views are, instead probing whether he still has his phone number

. Despite Johnny’s best efforts to act nonchalant and somewhat cold by hardly looking at Omar, the couple of times their eyes catch each other are poignantly loaded with familiarity. Indeed, Johnny has his number.

Omar: “Call us then.” – and Johnny finally cracks a smile.

Johnny: “We can do something now, just us.”

The ‘just us’ is of course especially significant in suggesting to the viewer that this is no ordinary boy friendship. It’s romance. Cut to when Omar is waiting for Johnny-boy’s phone call and catches his debilitated papa (Roshan Seth) up on the consequential meeting. The man isn’t happy at the return of “the boy who came here dressed as a fascist with a quarter inch of hair.” But Omar doesn’t particularly note his opinion (at least at that point) and is way more focused on the telephone ringing.

And the second he realises who it is: his cheeks are all roses and a massive grin spreads across his face. His father’s mutterings in the background become muted, and all he (and we) care about is his carnal hunger for Johnny. And Johnny surely feeds it to him. The two become partners both romantically and in business; striving to do “something big” together. They work to refurnish and run the laundrette, much to the dismay to Johnny’s former gang, who continually harass the establishment.

97 minutes of 16mm celluloid shot in 6 months, the comedy-drama was initially produced and made to be a television movie, entirely funded by Channel 4. The film later switched and had a theatrical release despite production plans and became the first British film to openly depict a gay romance. It was also Frear’s first international hit and put Daniel Day-Lewis on the map.

In January 2018, Indiewire and other news outlets reported that an upcoming television series adaptation loosely based on the film is being developed. With Kumail Nanjiani to star and co-write, and original screenwriter Hanif Kureishi (who was nominated for both an Oscar and a Bafta for his screenplay) to executive produce.

Literary References:

– Christina Geraghty. My Beautiful Laundrette: The British Film Guide 9 (2005).

7. C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005) dir. Jean-Marc Valee

Elvis Presley’s “Santa Clause in Back in Town” reigns as we begin by being encased in amniotic fluid, joined by a kicking grown foetus in his mother’s womb. This is Zak, and his French voice-over narrates:

“As far as I can remember, I’ve hated Christmas.”

We observe the very beginnings of Zak’s life, his birth on Christmas day- an occasion which always overshadows his birthday that he shares with Jesus. We follow him and his ‘crazy’ family through his childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, as he experiences tremendous Catholic guilt over his feared orientation. C.R.A.Z.Y is a Québécois coming-of-age tale spanning across a total of 31 years, from 1960 to 1991.

Longing for presents that are perceived by his father to be too overtly feminine, like a mini play pram, which he says will turn him into a “fairy”. Desperate to retain the love of his father, the five-year-old boy absorbs his father’s homophobic perspective and turns it on himself; praying throughout his life for God not to make him “soft”.

The inner self-loathing materialises through panic-driven asthma attacks, frequent bed-wetting, and borderline self-harming tendencies in which he forces himself to go through extreme conditions in the desperate hope that his debt to nature will result in him getting what he prays for. He holds his breath underwater, he walks through the dangerously freezing storms and through deadly dry deserts, but his interest in boys never dies.

Due to his fantastical ability to seemingly stop babies from crying and successfully pray for the health in others, together with his mysterious blond birthmark and his connection to God on his birthday, his tender mother firmly believes that her Zak is “special”, gifted by a miracle. Initially having a strong relationship with his father, the sweet joyous bond shared between the two of them is soon shattered.

After watching his father leave for work, a seven-year-old Zac puts on his mother’s slippers, her salmon robe, and her dangling pearls. But while ogling at his baby brother, he is caught by his father who has forgotten his wallet, and “unwittingly, declared war” to him.

Solidly placed in the period it is set it, the film is full of iconic 70s clothes, timely Bowie and Bruce Lee posters, marked by a masterful soundtrack of which nearly 10% of the budget ($600,000) was spent on acquiring the song rights for over two and a half years. Vallée even gave up his salary to help pay for them. The theme of music throughout the film explores individual expression, familial bonds, and an attempt to constantly unify the father-son bond once broken.

And then broken again. We hear his father regularly sing Charles Aznavour’s “Emmenez-moi” (translates into English as Take Me), at every family party. He is also quite obsessed with Patsy Cline’s hit “Crazy”, of which each one of his sons’ names take after; C.- Christian, R. – Raymond, A. – Antoine, Z. – Zak, Y. – Yvan. Leading to the title of this family-driven drama.

Zak’s own personal tastes are secretly praised by his father, who claims he got his sense from yours truly. There’s Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones, The Cure, Jefferson Airplaine, Dámaso Pérez Prado’s “Mambo Jambo” (a beat also significantly utilised in Samuel Maoz’s recent Foxtrot), and a fantastic scene of Zak belting it out to Bowie’s “Space Oddity”, with full lightning bolt realness. As well as a traditional rendition of Jingle Bells, sung by Vallée himself.

It took Vallée ten years to write this film, co-written by François Bouley, whose personal experiences the film is partially based upon, the film succeeds in portraying religious-induced internalised homophobia within a punk who tries his best to seem like he’s not mentally tormented by his truth.

8. Call Me By Your Name (2017) dir. Luca Guadagnino

We open with a montage of overlapping photos of classically Roman bronze busts and statues with yellow crayon sprawl title credits superimposed on to them. We’re in 35mm summer, 1983, somewhere in northern Italy, and our protagonist is Elio (Timothée Chalamet). A distinctly thin, trilingual seventeen-year-old, whose hobbies include; waiting for the summer to end, reading books, transcribing music, eating peaches and swimming in the river.

Now, enter Oliver (Armie Hammer), a debonair twenty-four American graduate student who is helping Elio’s father Mr. Perlman (the delightful Michael Stuhlbarg) with his anthropological work for the summer. He’s staying in Elio’s room and Elio has moved to the bedroom next door, which is interconnected by an ensuite bathroom and a separate door, making it a total of three separate doors (and a balcony) they can access to see each other in secret.

We know an eventual gay love affair is going to happen based on the pure hope that Elio and Oliver take advantage of their secret-tunnel convenient set-up for secret sex trysts. And they do. Lots of doors are promised to be slammed in this film. This is Luca Guadagnino’s coming-of-age/romantic drama “Call Me by Your Name” (2017).

As opposed to most features on this list, this is a film void of hatred. All the characters are not only nice, but they’re caring, empathetic and helpfully experienced individuals who do not seem to subscribe to the notions of homophobic-induced negativity. They only discuss beautiful things; life, cinema, philosophy, art and literature, and the etymology of words. So in this world, the audience gets to see the beauty there is in any type of relationship. Everything is rightfully beautiful when enshrouded by sun, sea, trees, and a Sufjan Stevens score.

This LGBTQ+ film effortlessly captures the purity and beauty there is in lustful crushes doomed by expectant society standards, especially during a time not so long ago when homosexuality was illegal (and still is in around 71 countries). Because of this context, unspoken desires are represented by symbolic male visions of Hellenistic and ancient Greek sculpture, rich in the classical ideology of finding distinct beauty in the human form.

Heavily recalling the strong association between the ancient Greeks and homosexuality since historical evidence suggests that the Greeks were one of the earliest civilizations to embrace fluid sexuality. On a group expedition, divers pull out a shipwrecked kourus boxer from Lake Garda and significant prominence is given to the statue’s arm, as it is used as a pseudo-olive branch of peace between the two’s growing tensions that were initially masked as slight distaste for one another.

In another scene, Mr. Perlman and Oliver catalogue slides of sculptures influenced by Praxiteles. Their conversation highlights Oliver remarks: “They’re all so incredibly sensual”. Mr. Perlman ironically observes: “Not a straight body in these statues. They’re all curved. Sometimes impossibly curved. And so nonchalant. Hence their ageless ambiguity. As if they’re daring you to desire them.” Guess who Oliver must be thinking about as he looks at the curly-haired statue?

Guadagnino’s usage of art as a metaphorical parallel to show Oliver’s interest in men and temptation to pursue a relationship with Elio reflects his interests and perspective of the film primarily being about the “beauty of the newborn idea of desire, unbiased and uncynical” rather than minimising it as a simply definable “gay” movie.

The Freudian term scopophilia seems to perfectly represent a central theme in this romance (and in most features on this list). Referring to the ‘pleasure in looking’. Psychoanalysts see stares and the act of observation as an expression of sexuality, to the sexual pleasure derived from looking at erotic objects, say naked statues or wet bathing suits dripping into the bathtub. Peaches and billowy blue shirts. We never know what Elio feels at first by what he says, but how he looks at Oliver.

Take the Psychedelic Furs’ Love My Way? Dancing scene. Elio sits, smokes, drinks some drink, and just looks at Oliver dance to the song. After a couple of beats, he joins Oliver dancing, never directly with but just near. Lancanian theory also suggests that scopophilia could also be applied to the understanding of why audiences love and derive pleasure from cinema. Their stares mirror ours as we watch them, also reflected by Sufjan Steven’s lyric “Is it a video?”

(Bonus: The Furs’ lyric “There’s an army on the dancefloor.” – indeed, an Armie Hammer).

Literary References:

– Jacques Lacan. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis (1994)

– Jacques Lacan. Television (1990).

– Laura Mulvey. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1973).