5. Roger Deakins

This British cinematographer has been nominated for an Oscar 13 times and surprisingly has never won, but this does not demerit Roger Deakins’ work. He is currently one of the cinematographers with highest reputation in Hollywood. Deakins has worked in more than 75 films since 1975, and two of his most revered works were done in 2007 – “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford,” and “No Country for Old Men.”

The production scheme on which Deakins works is not one of blockbusters, but more low-profile films that allow filmmakers more control over their work. Deakins is a longtime collaborator of the Coen brothers and with them he has shown the wide range of styles he is able to achieve. The adaptability of Deakins and his perfectionism have been proven once again on the collaborations he had with Denis Villeneuve, whose style draws strongly from the Coen brothers.

4. Yuharu Atsuta

The last cinematographer who worked with legendary ascetic Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu was interviewed by Wim Wenders in his documentary homage to Ozu, “Tokyo-Ga.” The portrait that Wenders did of Yuharu Atsuta is extremely enlightening in the way that Ozu collaborated with his cinematographers.

Atsuta tells Wenders the story of how he became the department head for more than 20 years after several years of working as an assistant. During the long years that Atsuta served Ozu (this is the word he uses), he was cinematographer in Ozu’s most recognized films. He was the one who filmed the Noriko Trilogy with Ozu, “Late Spring” (1949), “Early Summer” (1951) and finally “Tokyo Story” (1953.)

Anyone who loves Ozu knows that he shot only with a 50mm lens, with very specific framings and angles and hardly making a camera movement. And we wonder what kind of work the cinematographer did with all of these limitations. Atsuta explains in “Tokyo-Ga” that he saw his work more as a service to Ozu rather than a creative endeavor, but it was precisely this perspective and this way of working that allowed Atsuta to participate in the creation of what may be the more distinctive film style in the history of this art.

Ozu was a known fan of Hollywood classics and Atsuta’s lighting schemes reflect this, but he manages to make the scheme more subtle and naturalistic so they do not draw attention from everything else. Atsuta depurated the technique as much as Ozu depurated his language, and by executing Ozu’s direction in the best way possible, he shot some of the greatest and most beautiful masterpieces of Japanese cinema. The way in which this cinematographer collaborated with Ozu may remind us of the no acting philosophy of Wu Wei, understanding why his work was so important.

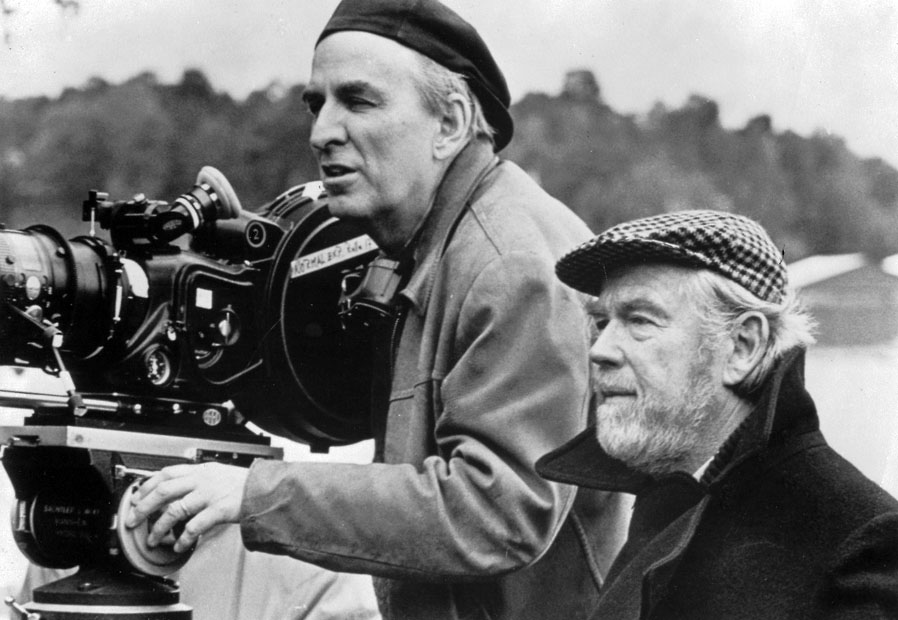

3. Sven Nykvist

With more than 120 credits, Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist made an outstanding career that started in Sweden in collaboration with Ingmar Bergman, and culminated in Hollywood where he collaborated on iconic films.

Close to the end of his career, Nykvist also collaborated on Tarkovsky’s last film, “The Sacrifice.” Nykvist tells that when he arrived to Los Angeles to join the guild, he was asked many films he had made, and when he answered 70, people thought that he had said 17, and when he clarified and was asked how many he had made with Bergman, he answered that with him it indeed was 17.

Nykvist was not the only cinematographer Bergman worked with, but he was indeed the one with whom Bergman made his most visually powerful films. In Sweden, Nykvist executed some of his most demanding films, such as “Winter Light” (1963), which was shot entirely with natural light, and “Persona” (1966), in which his talent to illuminate the human face can be seen at its highest.

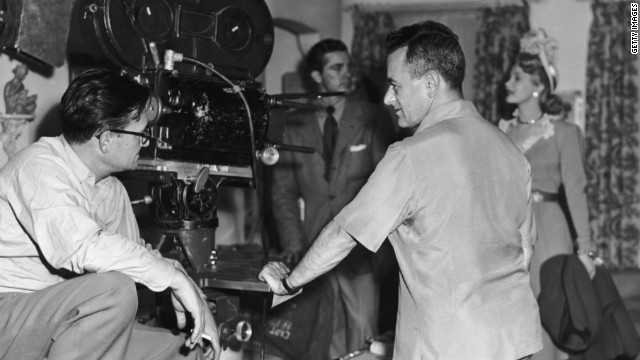

2. Gregg Toland

Few directors share the credit of a film with their cinematographers in the way that directors shared it with Gregg Toland. The legendary Orson Welles even put the credit of D.P. along with his direction credit.

Toland was the cinematographer who along with Welles, made the film that is conceived as the start of an era: the era of Modern Cinema. “Citizen Kane” (1941) was a film in which Tolland put all of his genius and techniques, such as deep focus that allowed Welles to give the mise-en-scene, the place it needed in film form.

But “Citizen Kane” wasn’t just the culmination of Tolland’s career. He worked with William Wyler, John Ford, Howard Hawks, and more of the greatest and most recognized directors of his era. One could say that Tolland’s techniques are as important as the mise-en-scene of this directors. This means that Tolland is one responsible for stretching the film language as an art form in a way that shaped films to come for many years, even in the current time.

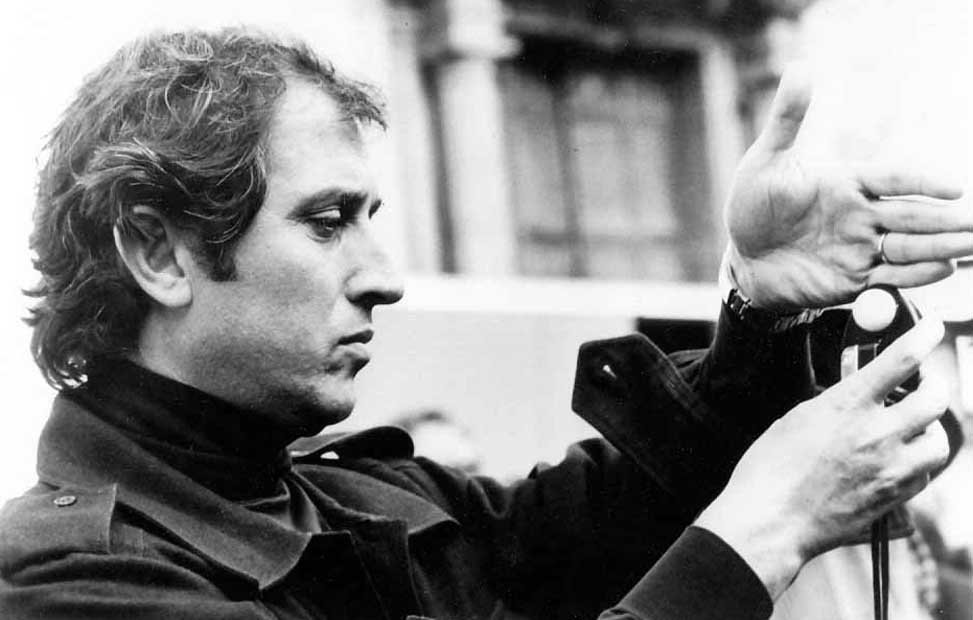

1. Vittorio Storaro

Winner of three Oscars, Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro is one of the cinematographers who has influenced both industrial and independent filmmaking. He has worked with a wide range of the greatest directors in the medium, and proof of this are his three Oscars: one in 1980 for “Apocalypse Now” (Francis Ford Coppola), another in 1982 for “Reds” (Warren Beatty), and the last one in 1988 for “The Last Emperor” (Bernardo Bertolucci). These films have made him internationally recognized.

In his interviews, Storaro talks about going beyond technique of lighting; he complains about schools only teaching “how to do it” and not “why to do it.” He talks about the philosophy of lightning and how light schemes can be as significant and acting. With the conception of his endeavor, Storaro has made some of the most expressive films in light terms such as “Il Conformista,” shot in 1970. He became one of the first references on a more artistic conception of the role of the cinematographer.