A definition:

bold

1. Fearless and daring; courageous: a bold leader.

b. Requiring or exhibiting courage or daring: a bold voyage to unknown lands. See Synonyms at brave.

2. Unduly forward and brazen; impudent: a bold, sassy child.

3. Strikingly different or unconventional; arresting or provocative,

4. a. Clear and distinct to the eye; conspicuous: bold colors; a bold pattern.

b. Strong or pronounced; prominent

The Bible states that the meek shall inherit the earth. This is a nice, if quaint, notion. It’s not, to date, been true of the world at large and it most definitely is not true of the cinematic world. It would be hard to argue that any safe, mild and conventional film has ever stood the test of time, certainly not in the minds of discriminating viewers. (Such films often are hits of the day, but are thereafter forgotten and usually quickly.)

The following list celebrates films whose makers couldn’t or didn’t play it safe. The fact that most of these films are well remembered classics today disguises the fact that they all, to one extent or another, were big gambles. Some were hits in their own time and some weren’t. However all have stood the test of time and are ample displays of the virtue of boldness.

1. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919)

Germany in the years just after World War I was not a pleasant place, to say the least. The country lay in ruins after the war and the economy, among other things, was also in ruins as a result of the war. Oddly, even as the country drifted towards a tragic totalitarianism, the arts surged amidst the chaos (not an uncommon occurrence).

Though there would be great achievements in painting and literature during this time, the emergence of Germany as a world class film making power was truly astonishing.

As a producer of films, it was second only to Hollywood and artistically, it was second to none. Ironically, though there had been earlier promising films, the picture that truly inaugurated this golden era was one which had to be boldly made out of necessity.

Just after the end of the war, two young veterans of the conflagration, Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, hoping to get into the film industry, co-wrote a script concerning an evil mountebank infiltrating a small town and using an eerie somnambulist he keeps in a box to conduct a murderous reign of terror.

The film was to be an attack on mindless and absolute authority (somewhat mitigated by a studio mandated framing device, though even that is ambiguously handled). However, the tale of supernatural terror called for deeply shadowy and atmospheric photography, something not possible with the small budget at hand.

The solution, conceived by production designers Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig, was to heavily rely on the ideas of the expressionistic paintings and theatrical productions then coming into vogue (and which would make a permanent mark of their own).

Instead of realistic sets with shadows cast with the help of powerful lights (and rationed electricity came at an exorbitant cost in that place and time), the production abandoned any attempt at realism, opting for an enclosed, ultra-expressionistic world of sharp and jagged edges, distorted perspectives, objects out of scale to the real world, and shadows painted upon those sets to indicate sinister going-ons.

Likewise, the actors (Conrad Viedt, Werner Krauss, Lil Dagover, etc.) gave suitably stylized performances while sporting appropriate (and equally eye-popping) make-up and costumes. Truly, it looks like an expressionistic painting come to life and displayed the idea that fictional cinema requires a transformative style appropriate to the nature of the film, not just a documentary-like realistic rendering.

Though there were some critical holdouts, the majority of the film critics of the time (admittedly, an embryonic group) gave it good to enthusiastic reviews, something carried over internationally (not an easy thing for an unpopular and defeated country to achieve).

However, it wasn’t a huge box office hit domestically or in foreign markets due to being too unusual and unsettling. However, to this day, anyone studying or just interested in cinema history knows this film, which has a following to this day.

2. L’Age D’Or (1930)

In the early decades of the 20th Century, Spain was still a devoutly Catholic and deeply conservative country. That makes the fact that the era and country produced such skillfully talented and subversive artists as film maker Luis Bunuel and his early partner-in-crime, the great surrealist artist Salvador Dali all the more remarkable.

The pair had caused quite a stir in 1929 with their surreal-avant-garde short film Un Chien Andalou, with its unforgettable (no matter how hard one may try) slit-eye imagery. However, that sample couldn’t prepare the country for the feature length film the pair would perpetrate the next year. That film was L’Age D’Or (The Golden Age).

L’Age D’Or is so revolutionary that even describing it is a daunting task. After starting off with an odd and purposely out of place documentary piece concerning the lives of scorpions, it then switches to the exploits of a young couple trying to make love. However, everyone and everything tries to put paid to their efforts, including the church, the government, several social institutions, and a number of individuals.

Why? Well, the pair, being in tune with nature, are violating a lot of antiquated social mores. During their fight against the powers-that-be, may surreal images come forward such as the couple joyously rolling in the mud during lovemaking, a horsecart with passengers calming riding through a society soiree in an elegant ballroom, and, most disquieting, the young woman rather obscenely kissing the toes of a religious statue.

However, nothing could top the unrelated (story-wise) final episode, which pairs Jesus Christ and the Marquis de Sade! How could they get away with this? THEY DIDN’T! The church in particular was not amused. Dali (rather cowardly, if shrewdly) recanted and escaped the brunt of the ecclesiastical wrath (and continued to make subversive art without involving religion).

Bunuel wasn’t so lucky. The church banned him from film making…for life! Thankfully, that didn’t quite happen but it took him two decades and a change of hemispheres (ironically to also Catholic Mexico) for him to get back to creative film work.

It goes without saying that the church also fixed it so that L’Age D’Or was DOA in all Catholic counties (and such people who had already seem it included a number of outraged viewers). However, like its director, the film has survived its time in great style and is a staple of film history.

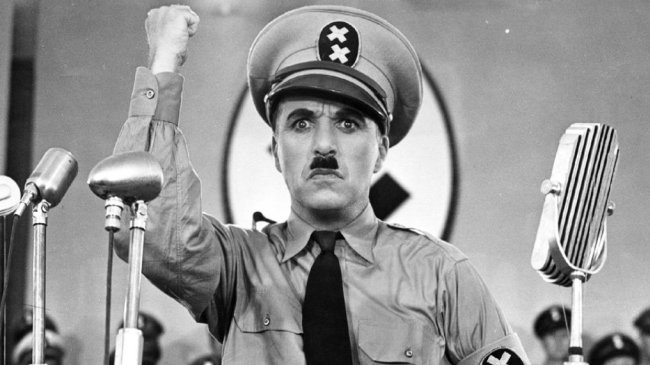

3. The Great Dictator (1940)

Charles Chaplin was unquestionably a bold individual in his off-screen life or he wouldn’t have survived the slums of Victorian era London to become one of the true pioneers of the early days of cinema. However, though quite brilliant, his work during the silent era wouldn’t be considered bold per se.

However, the coming of sound (and the fact that his fortune and not just fame, but place in film history, was secured) stimulated a boldness in him which allowed him to release both 1931’s City Lights and 1936’s Modern Times as silent long after the silent era ended.

However, his first truly bold stoke in creating a film came with his belated first talkie. By a wild quirk of fate, Chaplin’s famed Little Tramp character (who did not resemble the non-dramatic Chaplin) and a certain fascist despot then making indelible and horrible headlines looked very much alike (and, wilder yet, Chaplin and Hitler were born only a few days apart during the same week!).

Chaplin got the idea to lampoon Hitler, while also playing a meek little barber who happens to resemble the evil strong man. Today, with the current irreverent comic environment, making mock of Hitler might seem like shooting fish in a barrel.

However, at the time, even though Europe had already been engulfed in war, many of the Jewish owned Hollywood studios were still trying to tap-dance on a fine line that would allow them to keep the lucrative German/European market (only Warner Brothers stood against Hitler).

Chaplin was releasing through his company, United Artists, which, after almost two decades, was still struggling financially. Making such a powerful enemy would do the company no financial good.

Also, though many in Hollywood backed down to Hitler financially, they were appalled personally by the idea of making a comedy about Hitler (famed malaprop addled producer Samuel Goldwyn famously stated that he already wasn’t laughing while Chaplin’s film was in production).

Added to this was the fact that Chaplin’s appeal in sound films was totally unknown and he was making a most high-profile talkie debut a dozen years after sound came in. Happily, the film was an award laden and nominated triumph with such memorable moments as the dictator’s dance with the globe.

Today it’s obvious, as Chaplin stated to one degree or another, that he didn’t know of the horrors of the concentration camps (the few scenes in one near the film’s end look like something out of the Keystone Kops) and that aspect looks naïve now, and Chaplin’s closing speech was always a matter of conjecture. Still, the courageous film is great in many ways (and the next Chaplin film, 1947’s Monsieur Verdoux, also bold, shows that all gambles don’t pay off).

4. Kiss Me, Deadly (1955)

Director Robert Aldrich had a most interesting life and career. Though he was raised in a rarefied environment, being a close relative of the Rockefellers, his sensibilities were vibrantly blue collar (and pictures of him could pass as ones taken at Teamster headquarters).

He nevertheless entered the film world at ground level and first worked his way up to becoming one of the industry’s top assistant directors, laboring under cinematic greats such as Chaplin (1952’s Limelight) and Jean Renoir (1945’s The Southerner).

However, he wanted to make his own films and did manage to make the leap in the early 1950s. In an age where “good taste” was a (over)valued commodity, Aldrich’s films, mostly westerns, action films, mysteries, and war films, were a jolt.

No one would ever use such words as delicate, sensitive, subtle, and refined to describe any Aldrich film. However, their course but vibrant life force was always one of the best elements of his works. The critics rarely liked and the public only sometimes came.

From a distance before filming, 1955’s Kiss Me, Deadly would seem a safe choice. One of the most popular US writers of the post-World War II years was mystery/suspense author Mickey Spillane, who mostly wrote stories concerning Mike Hammer, an outrageous fascist private eye who never waits for the law and always takes jaw-droppingly violent justice into his own hands…and never feels less than right about it.

It was also quite obvious that Spillane saw Hammer without irony and approved of his methods (and always told his tales in Hammer’s first person voice, something not included in this film).

A small film company called Parklane Films, which released through United Artists, managed to wrangle the screen rights to Spillane’s novels and had released a few adaptations which were about what their source deserved.

Then, feeling that Aldrich’s work had much of the same crude electricity as the books, the company approached the director to adapt the typical Hammer novel Kiss Me, Deadly. Well, the result was anything but typical. Aldrich and his chosen writer, noir icon A.I. Bezziredes, decided to make an anti-Hammer film.

There would be plenty of visceral violence, as in the novel, and the guardians of good taste would take umbrage to it. However, biting the dust alongside the first person narration would be the novel’s basic plot (involving a suitcase full of illegal drugs).

This Hammer would be chasing a mysterious box alright, but what it contained would turn out to be one of the jawdroppers of 50s cinema. Featuring veteran movie bad guy Ralph Meeker as Hammer, this is an apocalyptic film, showcasing speed, confusion and chaos. Culture and honor have flown out of the window long ago in this world, with only a creep such as Hammer to look to as a hero.

Well, no one expected the US critics to like this…and they didn’t. The public was somewhat kinder, though the film wasn’t a top hit. However, the French critics of the Nouvelle Vauge were quite impressed (and, indeed, would promote Aldrich to the rank of auteur from the industry hack status accorded him by Hollywood).

It would take about two or so decades for viewers outside of Europe to catch up to this opinion (and also involve restoring the oddly truncated finale sported by most extant prints to its full terrifying power).

Kiss Me, Deadly has never crossed over to the good taste category but its many modern fans wouldn’t have it any way but the blunt and forceful mode in which it exists.

5. Breathless (1959)

The young critics of the Nouvelle Vauge loved not “films” or “cinema” but movies. Being located an instructive distance from Hollywood, they could see the forest for the trees and found that much of the conventionally approved mainstream cinema was lifeless, stilted and artificial while many disapproved of films that more or less occupied the margins of film history had a life force, ingenuity and spark that made them good film making with the ability to excite the viewer.

The remarkable thing concerning this group of young critics/film historians was that they, in the end, were a bunch of doers, not just sayers. Most of them, who generally started by working for the distinguished French film journal Cahiers du Cinema, became film directors and screenwriters. Many of them were fine film makers (with Francois Truffaut perhaps being the most beloved) but perhaps the most cerebral of them all was Jean-Luc Goddard.

Goddard seemed to look at the world in a unique way. He had no use for sentiment or convention. He didn’t so much make films as unmake film genres and dissect ancient movie clichés and tropes.

Perhaps the best way to describe a Goddard film is to say that it would be a meditation on some aspect of film culture (and modern culture) employing a style simultaneously absurdist/expressionist and grittily realistic. Goddard didn’t just develop this style over several pictures. It was there from the time of his revolutionary first film, Breathless.

Breathless tells the rather trite story of the fall of a young punk (the brutishly attractive, Brandoesque Jean-Paul Belmondo, in a star making performance), on the run after he shoots a cop and holds up with a dangerously capricious sometimes love interest (Jean Seberg, a lovely Hollywood cast-off, due to a couple of high profile flops, but proving a revelation in this type of intuitive film making).

The handling, however, was as fresh as the plot was old hat. Goddard uses many of the purposely jarring methods of filming the story which were hallmarks of the Nouvelle Vauge. The film was shot like a documentary without traditional sets, opting instead for real locations.

The cinematography is as plain as news footage shot on the fly. The editing is disconnected and often lacking in continuity, reflecting the disoriented mind set of the main character (this type of editing is now known as the “jump cut”).

The soundtrack is at times tellingly disconnected from the image. The pacing was also quite notably fast, fast, and faster! The film simply burst with youthful excitement and innovation, turning an old story into something which felt new and certainly captured a large share of young viewers of the day (and for many days thereafter).

Goddard impudently dedicated the film to the Hollywood poverty row studio Monogram (no bastion of high art) while helping to point the way into a thrilling new era of movie history.