8. La Nuit Américaine (1973)

“A movie for people who love the movies,” posters of François Truffaut’s “La Nuit Américaine” mention. Truffaut was a charismatic man who was saved by cinema. It’s known that his path in life would have possibly been much different if he hadn’t met legendary film critic Andre Basin. He dedicated his film “400 Blows” to Basin, for changing his life and introducing him to filmmaking, and in a sense, he dedicated his film “La Nuit Américaine” to other people who love the movies.

A film production intends to carry out shootings of several scenes at a setting in Nice. The team is multifarious, the technical requirements are endless, and unexpected problems occur one after one. Romances, quarrels, blue moods, even sudden deaths take place, disturbing the orderly prosecution of the shootings. Under the time pressure, the director can’t sleep in peace at night. Eventually, even if a lot of circumstances didn’t evolve exactly as they were planned, the film was given an end.

Through this film, Truffaut gave the audience a chance to meet a cast and crew, watch the daily routine of a film production, realize the mundane character of the procedure, and have fun.

7. Kings of the Road (1976)

Lonesome, distant, and dramatically terse, Bruno travels with his van from cinema to cinema, since he is a projector mechanic. Robert, a man who seems to be in a state of suspended animation, makes an unanticipated entrance in Bruno’s life, and from this day forward, they carry out a common journey along the border of West and East Germany.

Along these lines, a road trip of two silent, alienated, and emotionally exhausted men sets off. It’s a road trip of a different hue, qualified by a pensive mood, a poetic spirit, and great visual beauty occurring in its well-framed black-and-white photography and expressed through its atmospheric music. Throughout this course, few things happen, few words are articulated, but many ideas and thoughts are captured. These men are meant to accomplish a personal transcendence and surpass together plenty of borders.

Wim Wenders, in his artistically plangent film “Kings of the Road,” through a crystal-clear and simultaneously multifaceted thematic approach, deals with some of the principal topics emerging in his filmography: isolation, the decay of human relationships, long-term psychological loads, bottled-up emotions, and family decomposition.

Yet, the mastery of this remarkable work is found in the parallelism between the story’s narrative and the illustration of the movie houses. All of the cinema halls that Bruno visits are downfallen or almost abandoned, representing mental states that both protagonists represent themselves. Bruno may be a technician, but he sustains a kind of silent passion for the seventh art. He is a pure film lover who stays hushed until he abruptly screams at the top of his lungs.

Bruno always listens to the owners of the halls. They speak about their work and their history. He collects knowledge, receives food for thought, and even evolves as a person. An old lady, who feels like closing down her cinema, says that she can’t stand watching and projecting films anymore, since they unlimitedly expose every component of human nature. This film elaborates on life through cinema and at the same time elaborates on cinema through life.

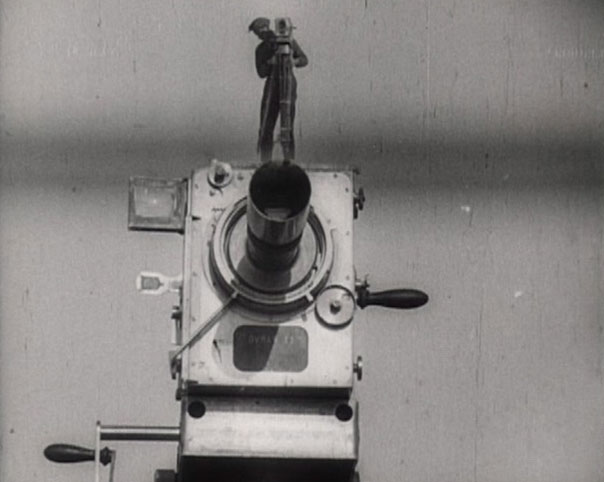

6. Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

Groundbreaking in its era, awe-stirring nowadays, and timelessly without an equal, the film “Man with a Movie Camera” illustrates a city’s whole day through a barrage of daily images. Withal, this extravagant cinematic synthesis was completed after several years of shootings in different cities. One could say that it seems more like an avant-garde documentary than a film, since there are no protagonists, no script, and no specific start line or destination.

This piece of art describes the simplistic base of life and immortalizes the multileveled cultural state of an era, rendering an artistic character to ordinary sceneries, people, and activities. In such a way, Dziga Vertov created an iconic mosaic of the daily pictures in Eastern Europe that owns unparalleled esthetical strength and conceptual value.

Perhaps every film lover on earth has watched this movie again and again in order to satisfy their senses, enjoy its breathtaking speed, and travel back in time. Still, the essence of “Man with a Movie Camera” is the observation of the primal scopes of filmmaking.

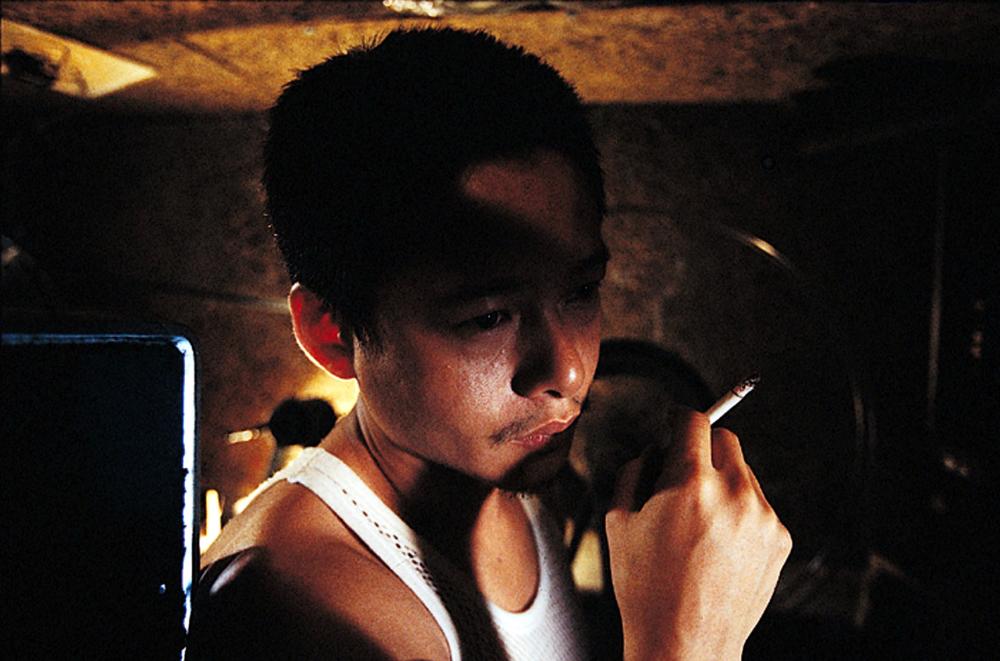

5. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

Going to the movies is conventionally a group activity or a common activity for lovers. Nevertheless, experiencing a film ‒ even if it’s possible to share thoughts and ideas ‒ is a personal matter of complex inner procedures.

In an overcrowded city of China, nobody goes to the movies anymore. In this fashion, a decayed legendary movie house closes down. Only few spectators have shown up to watch the last picture show.

It’s a rainy and gloomy night. Few people enter the Dragon Inn. They all sit away from each other, seeming to fear even the simple distant eye contact. The time goes by, and the empty seats look more and more bigger, greater, and emptier. During the intermission, the male audience meets at the toilets. No one dares to start a conversation. Still, they stay motionless next to each other, while the minutes come and go.

The film “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” deals with one of the major themes of Taiwanese New Wave Cinema: alienation and eroded communication. The approach on this topic is clear, expressed by a real-time, laconic narrative. Accordingly and in a unique way, the film is dedicated to lonely people.

Quintessentially, cinephiles are always solitary souls. Thus, Tsai Ming-liang uses an ideal setting for his film in order to focus on loneliness. For a film lover, the closing down of a cinema hall signifies a small tragedy. This film exposes the sense of isolation and social depression, accentuating the interactive relationship of society and cinema.

4. The Travelling Players (1975)

One could say that Theo Angelopoulos is a big part of Greek cinematic history. Essentially, he created a historic cinematic land all on his own; a land synthesized by a phenomenal artistic character, heterodox handling of the space-time continuum, and abstruse spotlighting on humanity.

His film “The Travelling Players” is a deeply philosophical, bold, and versatile piece of art to an almighty degree, dealing with the social acceptable and intertemporal forms of violence. Standing against the status quo, and defying the outrageous political dominion of his era, Angelopoulos exposed plenty of Greek or panhuman pathologies through the revolutionary and sincere prism of “The Travelling Players.”

The story follows a traveling repertory that wanders through Greece in order to present performances of a folk play. The actors have ancient Greek names and carry with them a musician, an old woman, and a child, synthesizing a picturesque team. They move through space and time, intersecting with crucial and bloodstained points of Greek history.

Piece by piece, Angelopoulos unfolds a tangle of political corruption, social analgesia, and effete tradition, always focusing on the restrained souls and tarnished mentality of the simple people. An intensively dramatic ambience deepens throughout the film, reflected on gloomy and eroded folk elements, on silence, on decay, on music.

The film definitely challenges evasive feelings of frustration to every spectator, but an actual comprehension of all the aspects of its multidimensional entity seems like an intellectual conquest. It’s an experience that doesn’t guide the audience, but attempts to navigate them within the mystified, puzzling, and at once clear labyrinths of arthouse cinema.

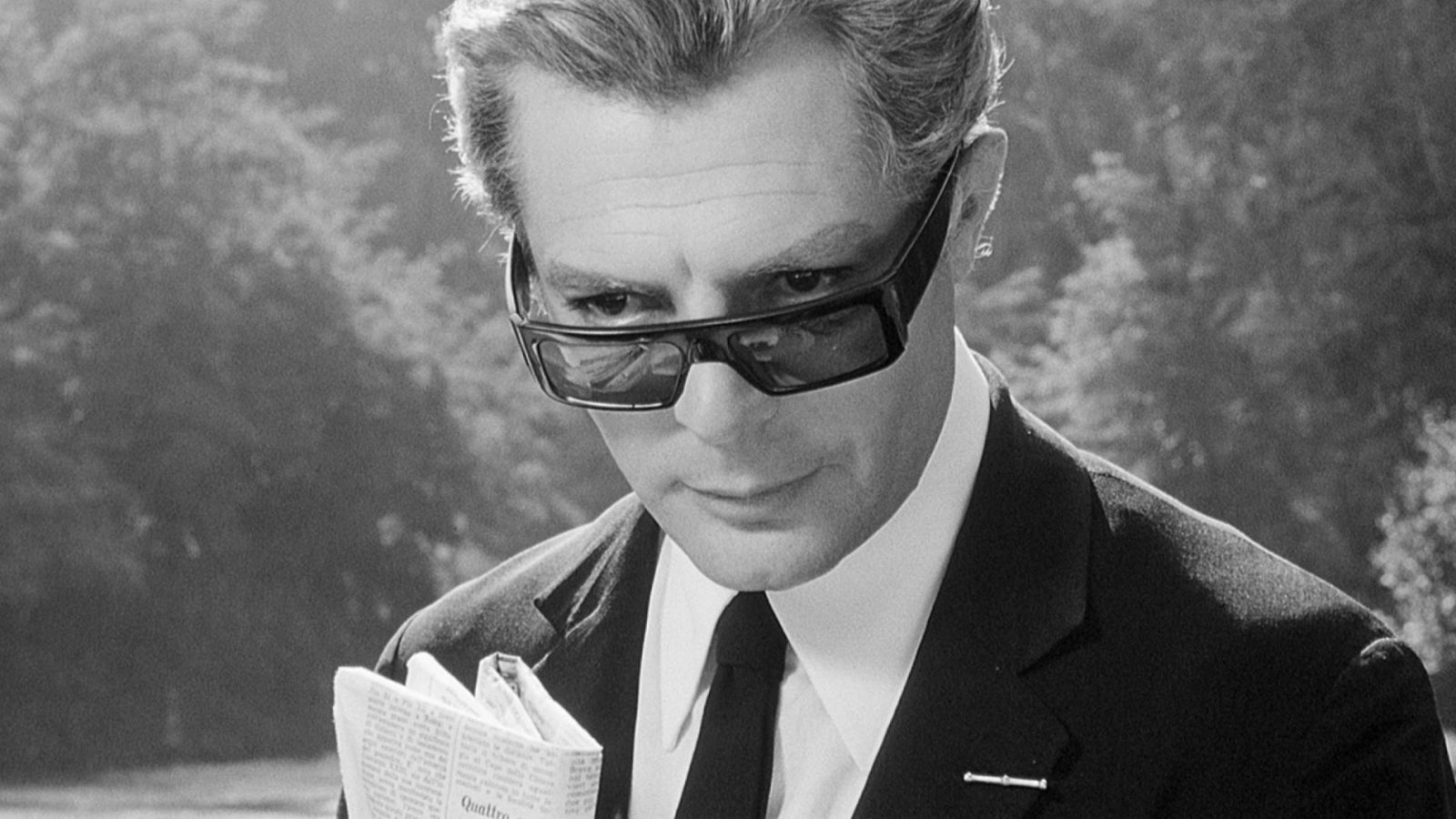

3. 8 ½ (1963)

Inspired by the lack of inspiration, wedged in between Federico Fellini’s 8th and 9th feature, and expressing an absolutely personal tone on many levels, “8 ½” is one of Fellini’s best works and one of the best movies ever made about cinema.

What happens when one of the best filmmakers on earth is confronted with recession of creativity, submerged in the rowdy world of spectacle, and in his convoluted personal life? He mirrors his intellect on the astonishing figure of Marcello Mastroianni and creates a visually stunning, pithy, and wistful projection of his psychological profile.

There’s something exceptionally remarkable about “8 ½.” Director Guido Anselmi is confronted with the worst consideration that could ever be engendered in the brain of a filmmaker: he’s afraid of having nothing more to say through his work.

After all, as he struggles to avoid his agonizing cerebral situation, resorting to his memories and letting loose to his innermost thoughts, he finds out that as long as one expresses his real self, worldview, and personal experiences, there is always something meaningful to talk about and manifest to others.

2. Underground (1995)

Letting out a little bit of Theo Angelopoulos’s mood, and entailing a shred of Andrei Tarkovsky’s visual style, this is Emir Kusturica after all… his absolutely one and only film “Underground” certainly includes scenes of bridal veils hovering, the death of a woman after giving birth, and a cortege of Balkan musicians.

During World War II in Belgrade, a socialist community takes cover in an underground settlement, in order to protect its safety, morals, and political beliefs. Most of the population lives a blinded life in an artificial fish bowl, without having even a clue about the situation taking place on the surface. Progressively, it becomes clear that some of the community’s leading figures aren’t the unblemished rebels everyone assumes they are. Still, few pure ideologists are diffused in that welter of expediency.

After the end of the war, the moderators of this underground microcosm are treated as heroes. A movie about their lives is being filmed, projecting a crooked version of the actual events. Yet, things aren’t meant to stay calm forever. During the civil war, the opportunistic quality and the fake character of several events comes to the surface, causing incurable emotional pain to the pure believers.

Substantially, “Underground” is a mourning symphony for the death of a tortured nation, and moreover, a multiple doubt of humanity’s deeper and genuine integrity. Each main character comprises a complex canvas on witch Kusturica portrays plenty of universal and timeless attributes, expressed through thorough allegories and artistic artifices.

Throughout the film, various profound thoughts are effortlessly engendered, drifting in its real substance and at once surreal atmosphere, and even moving from tears to laughter and from laughter to a form of fragile silence. “Underground” represents the seventh art ‒ or art generally ‒ at its best, accomplishing a holy duty: it creates a whole new point of view, manifests the conceptual boundaries that often are imposed on weak people, and bravely exposes even the most untouched and painful truths.

1. Amator (1979)

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Amator” occurred before his recognized filmic creations, and like this, it puts on the spot some of a rising filmmaker’s primal efforts and agonies. The film observes the gradual transformation of a simple man into an actual filmmaker, who discovers his passion about making movies, and at the time buys a camera in order to film the first days of his newborn child.

Since the first second Fillip holds his amateur camera in his hands, he feels an indefinite connection with that magical item that records reality. Owning a camera is quite unusual in the space-time setting of the film, and thus, he is asked by his job to film a significant event. Fillip enjoys the procedure, being encouraged to go along with his new creative hobby.

Meantime, his wife more and more feels neglected by her husband, since he seems more passionate about filming the world around him than concerning himself with his family. And she’s right. The respective word for “amateur” in Greek means “lover of art.” A companion can never claim the leading role in an artist’s heart.

Progressively, Fillip discovers that filmmaking is a weapon, as a means of exposing, confronting, reflecting, and essentially impinging upon this world. He creates a documentary about a co-worker who suffers from achondroplasia. The documentary is projected on TV, affecting his bosses in a way he didn’t expect. As follows, he is frustrated and wonders about the meaning of his work so far, questioning the lines he should follow from here on.

His wife leaves him. The moment she exits the room, he moves his hands as if he could capture the moment with an imaginary camera. He’s left alone in the process of a valuable realization: filmmaking, more than anything else, should express deeply personal matters. Fillip takes his camera and directs it to his face. He starts to talk about that day, when his wife ‒ terrified, fragile, and hauntingly beautiful ‒ was in labor.