Even though a normal film is between 90 and 120 minutes, there are films that are other kinds of experiences. The greatness of some of these films relies on building a world that requires a longer period of time to be effective.

These films displayed a different rhythm and different styles that let us experience the film in an unusual way, but one that mesmerizes us to the point that the film’s length is not an issue but rather a virtue. Here is a list of 10 long movies we can’t get enough of.

1. La Hora de los Hornos (1968)

Addressed sometimes as the most important political film of Latin America, “La Hora de los Hornos” is a 1967 documentary on the fight against colonialism and imperialism that flooded Latin American in the 1960s.

Put together within an underground production scheme by Fernando E. Solanas and Octavio Getino over the convulsive decade of the 60s, “La Hora de los Hornos” was a 260-minute film that featured several testimonies and archived images of the fight for liberation against the oppressive regime of Argentina in the 60s. The film was and still is a landmark for political cinema and the revolutionary fight of Latin America.

“La Hora de los Hornos” is a film where an acute and critical point of view is displayed both ideologically and formally. Crafted with a structure that reminds the viewer of a written manifest melting with reportage, the film is a subversive landmark of cinema.

There are several sequences of the film that juxtapose documentary fragments with a critical and explanatory comment by the filmmakers and interviewed characters, displaying an unforgiving and uncompromised portrait of a deeply unfair society.

The film is a constant confrontation to the viewer, to whom it speaks directly using all of the elements of film form; take, for example, the initial montage of the film where, while the images are a mix of revolutionary quotes and archived videos, the sound shows the growth of a collective and subversive chant.

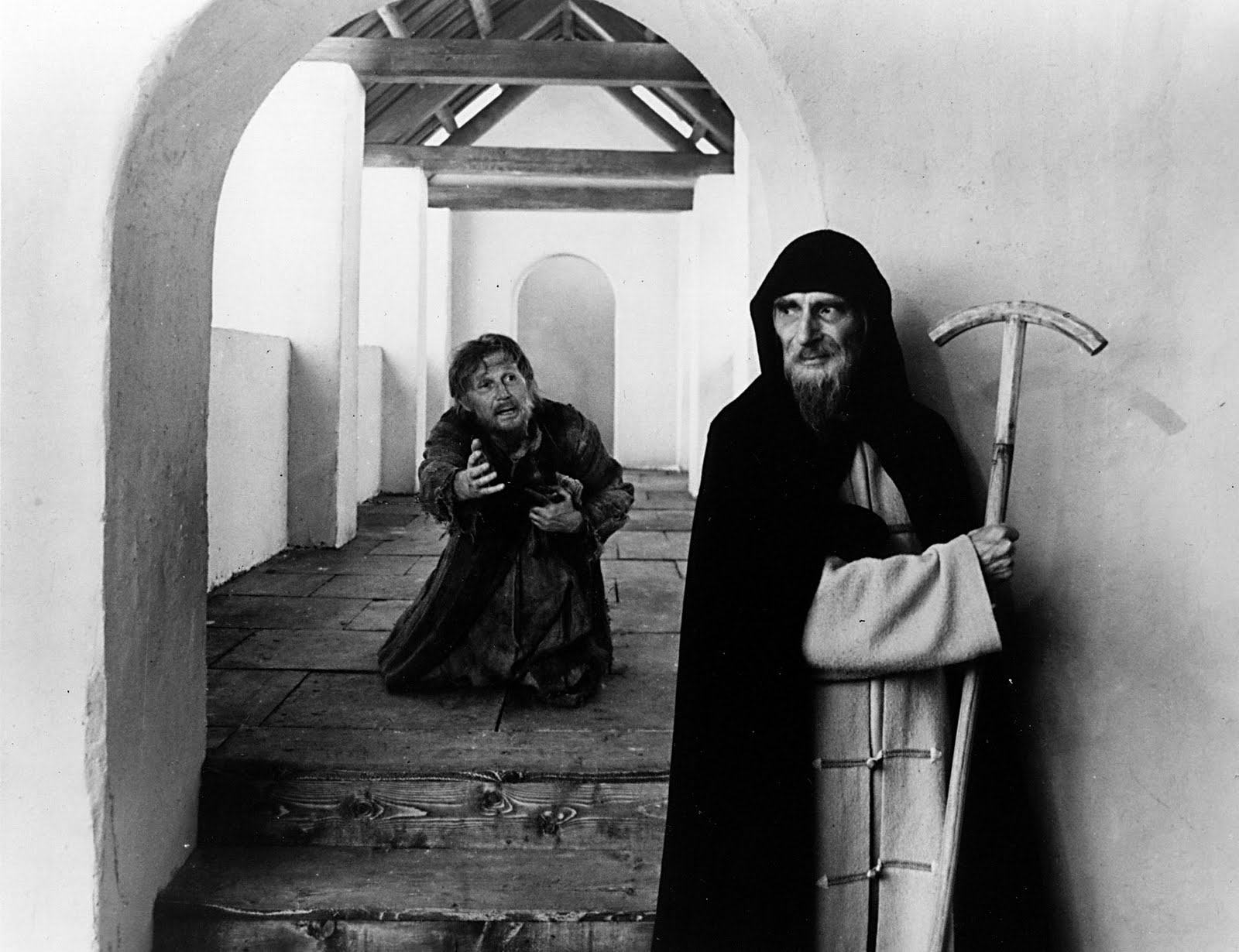

2. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Tarkovsky’s third film is a series of episodes involving, in one way or another, iconic medieval painter Andrei Rublev, who faces a time of crisis in which he questions the role he must play as an artist in a convulsing society.

The three-and-half hour film is one of the most celebrated in Tarkovsky’s cinema. In it, he creates a medieval Russia that feels both authentic and oddly contemporary. The classic ambiguity of Tarkovsky and his constant reflection is displayed in each episode of the film.

There are episodes in which Rublev is a mere witness to the events depicted and others in which he is the protagonist. Each episode is home to expressive interactions done with great sensibility where powerful cinematography, staging and acting are always present.

Tarkovsky creates a world of great beauty and constant suffering, in which the episodes create a powerful effect that build up to the last in which Rublev sees a young boy take a leap of faith, and through witnessing this, his inner crisis takes a new path that he has been searching for through the entire film.

3. The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

The Golden Age of Hollywood, when the great classics were made, was built by many foreign filmmakers who found in the rising industry of the Hollywood Studios an opportunity to create, and one of the most bright and respected of these filmmakers was William Wyler.

In 1946 he released “The Best Years of Our Lives,” a film that displayed a more realistic and critical approach to society, the result of the global shock of the Second World War. The 170-minute film displays the return of several war veterans to their small-town homes where they have to struggle with the fact that things are not as they were before the war.

Praised by personalities including Billy Wilder and André Bazin, this film is an achievement of cinema and humanity, in which Wyler puts all of his sensitivity and control into film form. The film is a great example of the cinema described by Bazin, which does not rely as much on the juxtaposition of images (even though it indeed plays a role) as it does the montage of the camera in relation to the scene. This technique allows Wyler to put the viewer in the perspective of witnessing the struggles of the characters, who are facing the hardships of coming back to a home that was not what they remembered.

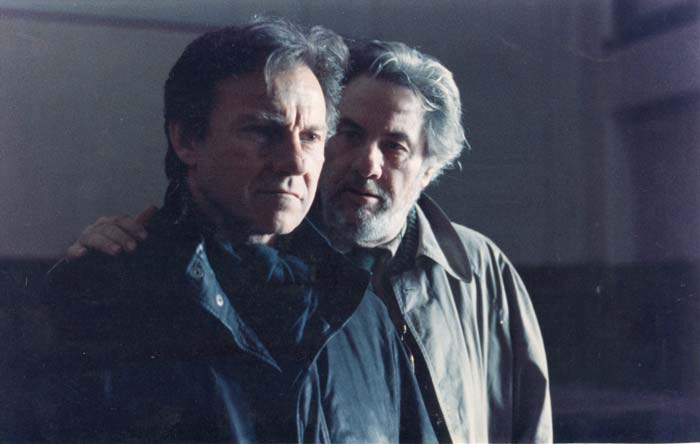

4. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995)

Released in 1995, this 176-minute film by Theo Angelopoulos is one of the greatest films within a very personal and human filmography. “Ulysses’ Gaze” displays the search of a nameless Greek filmmaker (played by Harvey Keitel) for the lost reels of film that were the first to be shot in the Balkans.

The search of the filmmaker for a common origin leads him to travel across Eastern Europe, reviving his past in an episode that melts the threshold between past and present with the unique language of Angelopoulos.

The simple premise of an adult man returning to his homeland in search of a lost object of the past lets Angelopoulos create some of the most memorable scenes in film history. His characteristic use of symbolic mise en scene in long shots and the mesmerizing atmosphere in which he built scenes, such as the dance scene in his old family house or the visit to Sarajevo, reveal the tragic nature of humanity as a subject of time and war.

5. Satantango (1994)

Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr is one of the most extreme and subversive directors of modern cinema. The language he developed through his career as a director (which he has said to be over after “The Turin Horse”) is one of extreme long takes with mesmerizing shots that at the same time display desolation and great beauty. Of all of his challenging films, it is “Satantango” that highlights as the most extreme experience, with no fewer than 450 minutes of screen time, during which the community of a collective farm and its failure in a beautiful black-and-white atmosphere of desolation is portrayed.

Even though the idea of watching an almost eight-hour film is quite overwhelming, the perspective that Tarr creates in his films is one that makes it worth it. In “Satantango,” the ordinary life takes a whole new dimension as the film reveals both the profound desolation of the characters and the intrinsic beauty of the decaying world.

The act of walking on a lonely road harassed by an inclement wind is an opportunity to show (without almost any dialogue) the weariness of characters who no longer believe in the project of the collective farm.