In the jewelry world its Tiffany. In the auto world its Rolls Royce. In old Hollywood it was MGM. There is always a gold standard bearer of some kind in virtually every field one might mention. In the world of home video, at least in the countries in which this company markets its line, that standard bearer is The Criterion Collection.

Criterion has had a long and distinguished, if rather circuitous history in the home video field. It was started by the much admired art house company Janus Films in partnership with the educational company The Voyager Press back in 1984. No, they were not releasing DVDs, and certainly not Blu-Rays back at that time.

Also, except for the tiniest handful of releases (three films to which they had reclaimed the rights, to be exact) they never released anything on the once popular, now quite inferior and extinct medium of VHS. Instead they released their product on the then emerging laserdisc format.

Laserdiscs might well be called the working prototype of DVD. Unlike VHS, they had sharp images and sound and could accommodate such things as chapter stops, additional material related to the main subject of the release, and, particularly after digital soundtracks came into being, the addition of alternate sound tracks commenting on the featured subject.

The even happier news was that the company intelligently filled these additional spaces with marvelous, instructive and entertaining material which greatly enhanced the main feature. Also, those main features weren’t put out in just any condition: the very best pre-print materials were sought for transfer and Criterion’s top technicians made sure that the transfers were flawless.

As the company’s reputation grew, they sought and often got input from the films’ directors and/or cinematographers with many world authorities on film also contributing. The bottom line is that if a film is chosen to be included in The Criterion Collection, then it will surely never have a better presentation and just the matter of it being selected is a great honor in and of itself since Criterion only tends to chose very superior films (and to readers of this, yes, some few selections aren’t that superior but artistic things are always in the eye of the beholder and some films get chosen for reasons past their intrinsic artistic value).

For all the great films which are, or have been, included in The Collection, there are many others which have not. While the films of the Janus Collection do form the core of Criterion (mostly foreign and art house classics), sub-licenseing from other companies have added many great films from other sources to the roster. However, for whatever reasons, legal, proprietary, physical, whatever, some remain out of reach.

Sometimes a company (one might well look at Paramount and the case of Roman Polanski’s 1974 classic Chinatown) wants to hold on to a film exclusively. Sadly, though, for many, if a film doesn’t have a Criterion version then whatever video version it does have, even a good one, seems lacking. (Even the classic videos of Warner Home Video got this attitude, though in the past few years Criterion has been re-releasing some of these films in versions which port over the extras virtually in toto and have virtually the same fine transfers!).

Listed below are some memorable films which are not in The Collection. Surely the reader will have their own wish list of Criterion should-bes (and films which once were in The Collection but which no longer are, aren’t included) . However, for now, these are a start:

1. Greed (1924)

Actor-director-writer Erich von Stroheim is a colossus of film history, certainly early film history. With his matchless (truly matchless) dedication to physical and psychological honesty (he NEVER met a kink he didn’t like) and his expert attention to even the most minute detail, there was no one quite like him in his own time and sadly few like him since.

Film was his canvas and, if he had been left to paint it as he wished, he might well be considered the of greatest of them all. Sadly, very few of the nine films he directed (all but one silent) exist in the form he intended. While some restoration was done to 1922’s Foolish Wives and 1929’s truly ill-fated Queen Kelly, the finest, yet most damaged, of his films was Greed.

Greed was taken, literally page by page, from the noted early 20th Century naturalistic author Frank Norris’ superb novel McTeague. This work tells the grim story of the title character, an unruly, unlicensed dentist plying his trade in late 19th Century San Francisco. His frenemy Marcus palms off his unwanted cousin/fiancee Trina on McTeague, only to have the woman come into a small fortune by winning a lottery just as the pair marry. A ruffled Marcus then turns McTeague into the authorities, ending his dental practice and leaving him unable to find work.

As this is happening, Trina, with her own money for the first time in her life, becomes an obsessive miser, refusing to use any of her money to help her husband or alleviate the situation. Clearly, all involved are on a collision course and it will end tragically (to say the least).

The basic story contained realistic, if not downright sordid, elements not usually tackled in Hollywood films. Added to this was Stroheim’s unusual ideas of casting (he detested “stars” and, indeed, the two times he was forced to work with stars were catastrophic to his career). He chose unknown Gibson Gowland for McTeague (his only other notable film with Stroheim’s 1919 Blind Husbands), study but not stellar supporting actor Jean Hersholt for Marcus and, most daringly of all, low comic actress Zasu Pitts as Trina.

The three times she worked with Stroheim were the only three dramatic roles she played in her extremely long career and he, and he alone, saw the great tragidenne lurking beneath her comic mask. However the huge element which makes Greed great is the breathtakingly painstaking amount of realistic (and, often, perverse) detail Stroheim injects into the project. If there is a phony moment in this film, a detective would be required to find it.

The killer in all of this, for the studio front office if not the public, is that, in its original form, the film ran nine hours! Stroheim suggested that it be divided into two parts which would play in theaters on successive weeks, as was being done in Europe around that time with films such as Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films (1921) and Die Niebelungen films (1924).

However, Hollywood wasn’t that progressive and the film was cut, first by Stroheim himself to four hours (his bare minimum)and, without him to two and quarter. Supposedly, the cut footage was destroyed, though phantom reports still surface saying that it survived. In 1999 there was a “restoration” using stills (and a copious amount were taken of the cut footage) that was a nice try and gives an approximation of what might have been with this film.

Sadly, the current owners, Warner Home Video, an excellent company in general for catalog releases, has a somewhat blind eye for silents. Though many silents, Greed in its new version included, have had a presence in the streaming world, few have been given a DVD release. Greed was given a VHS and laserdisc release many years ago when the rights belonged to MGM/UA but, as was the custom of the times and formats, those now obscure versions were rather bare-bones (and came before the revised version was created).

Greed is a milestone film and deserves a great video edition (such as other Stroheim works have been given by other companies). While silent films aren’t a major Criterion focus, they aren’t at all an unknown quantity to the company, either. Greed deserves the Criterion treatment.

2. The Thin Man (1934)

Speaking of Warner Home Video…back in the DVD heyday, that company achieved its highest sale figures for a vintage catalog release with a wonderful box set dedicated to those lovely, chic romantic comedies masquerading as murder mysteries, The Thin Man series.

The original film in the series was taken from a then-current best-selling novel by literary mystery maven Dashiell Hammet (and little did anyone know that it would be his last ever, though he lived on for many, rather mysterious, years thereafter). Though the author did not work directly on that film, he did contribute to the next two (more or less the last writing he ever did).

Every so often in film history (or just history, period) happy accidents take place and The Thin Man was one of them. Though the novel was selling briskly (there actually were no best seller lists at the time so who can say if it was one), mysteries, and comedies for that matter, weren’t taken all that seriously by the cinematic powers-that-were. A moderate budget (by MGM’s lavish standards, at any rate) was set aside for the project.

The directorial chores were given to studio director W.S. Van Dyke, know as “One Take Woody” due to his rat-ta-tat-tat shooting style. The leading man chosen was William Powell, a star since the silent days but a low burner sort of star mostly. His leading lady would be Myrna Loy, around also since the silent days, and then know mostly for playing, of all things, Oriental women, mostly vamps (impressive for a WASP from Montana).

The pair was chosen mostly due to their fine mutual chemistry in the then-recent hit Manhattan Melodrama (1934), a serious crime drama featuring Miss Loy torn romantically between D.A Powell and his childhood pal-turned-gangster Clark Gable (an actor Miss Loy would work with almost as many times as she would with Mr. Powell). None of these ingredients promised anything more than a decent, soon forgotten programmer, especially seeing how it would be made on a schedule of only eleven days! Well, how wrong was that impression!

Van Dyke’s loose, energetic style, not always right for “prestige” pictures (the boring kind) was just the right thing for this jaunty tale of a high-living, hard drinking society couple (she an heiress, he a former police detective happily admitting to living off her money) solving a murder mystery set in high society circles during the week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve.

Powell was about to set off on his finest period as one of the cinema’s great comic actors and Miss Loy never had a play a degrading Oriental role again (and today she looks like one of film’s great comic actresses, something she made look too easy to get much credit for at the time). Their characters, Nick and Nora Charles,have become synonymous with wit, sophistication, elegance and…well, a lot of fun.

It didn’t hurt that they also were “parents” to Asta (played by Skippy), a Cairn terrier who is the best canine to appear in a feature film. (Yes, that includes the ever-maudlin Lassie. By the way, Skippy also has a crucial role in one of Criterion’s best 2018 releases,1937’s The Awful Truth).

At the height of the DVD era, Warners was actually doing Criterion level work with many of their catalog releases. Sadly, as that era passed, many of those releases went permanently out of print. Now The Thin Man and three of subsequent five sequels are only available on a much cut-down two disc version largely sans extras.

Thankfully, the company now has an agreement with Criterion and some of its previous editions are being reborn on the Criterion label looking very much as they did a few years ago on the Warner label (and 2018’s re-release of 1945’s film noir classic Mildred Pierce is a fine example). To date the films selected have been of a very serious nature. How about it, Criterion? Something a bit less serious?

3. Johnny Guitar (1954)

The old saying is that a prophet has no honor in his homeland. Well, some films prove that to be true enough but also can show that the prophet can have honor even in his homeland provided a vast amount of time has passed, preferably if said prophet has died in the meantime. There can be no finer example of that than US director Nicholas Ray.

Though he worked in the Hollywood system for about a decade and half (though it seems longer, given the number of films present day critics and fans find notable)and had a big hit (with the younger audiences, anyway) with 1955’s Rebel Without A Cause, he was never truly Hollywood.

To say that the fit was uncomfortable would be a great understatement. Had the indie film movement existed in his own time, Ray would surely have been the king but, as it was, he had to struggle to make his films his own way. That struggle was never greater than evidenced by the making of his great cult oddity Johnny Guitar.

Joan Crawford, a truly incandessent but, by then, fading star was trying to take her career in her own hands in the early 1950s and found an unusual western novel centering on the battle between two exceedingly strong willed women over land that is soon to be valuable with the coming of the railroad. The saloon owning Vienna is a considered a “foreigner” with the locals stirred up againist her by the witchlike Emma.

Crawford, playing Vienna, bought the rights to the novel and sold them to Republic Pictures, a poverty row studio trying desperately to break into the bigger time (they had just had their all-time biggest hit with John Ford’s The Quiet Man in 1952 but timing wasn’t on their side overall).

The provision was that she came with the deal. She did not, however, get approval over much else and got a rebel director, who would end up in exile, a leading man (Sterling Hayden) who would join him in exile after being blacklisted, a screenwriter (Phillip Yordan), who would help the blacklisted, and a scene-stealing Oscar winning powerhouse of a supporting actress (Mercedes MacCambridge) Crawford would jealously try to have put on her own personal blacklist. It was not a happy group.

Added to this is the fact that Ray seemed to chose this film in which to try out all sorts of odd and new ideas. This was his first color film (and he would prove to be a master of color eventually) and it was done in the harsh, rather second-rate Trucolor system used by Republic. However, he does create an interesting color scheme for the films. Then there are the sets. Apparently, this patch of the old west was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright (Vienna’s saloon/casino is literally built into the side of a mountain).

Then there are all sorts of undercurrents built into the bizarre story. Emma seems to be a stand-in for Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his ilk, wanting to drive out any who don’t fit the pattern of the “norm”. She and Vienna perversely take on the roles usually given to male characters (yes, they end up shooting it out).

The male characters in the film are all oddly passive (and Hayden was the least likely actor In the world to portray that quality). In fact, if ever a film was the cinematic equivalent of a Rorschach test, this is it. It was all too much for the domestic market (though singer/songwriter Peggy Lee’s fine theme song was a big hit).

Happily it was and remains a favorite of European audiences and disciples of Ray. Jean Luc Goddard had his much beleaguered runaway lovers in the 1965 classic Pierrot le Fou stop to catch the film in a revival house!

Though the film has achieved a healthy cult following in the US over the years, a really great video version has been elusive. Republic went of business not too long after the release of the film.

The rights, along with most of the other Republic films were bought by early television packagers National Telefilm Associates (NTA), who changed their name to Republic Pictures Home Video when the VHS era started. They subsequently sold out to TV producer Aaron Spelling, who quickly sold the library to its current owner, Paramount Pictures (that library also contains some of the finest indie films made in the US from the 1940s to the early 197os).

All of this upheaval has, thankfully left the doors open to interested third parties sublicensing the films (Paramount literally has almost no interest in putting out catalog titles). In the laser era, several titles from this collection made it into the Criterion realm (and one wishes for the return of 1948’s Letter From an Unknown Woman!).

Those didn’t make into the DVD collection up to this point, though evidence on the streaming channel Filmstruck suggests that could be changing. Criterion has shown a penchant for Ray’s work (1951’s In a Lonely Place, 1956’s Bigger Than Life). Maybe Johnny Guitar’s day will come soon.

4. Rocco and His Brothers (1960)

Luciano Visconti is one of the greatest of Italian film directors (and just plain film makers period). An aristocrat by birth, an artist by temperament, and a socialist by choice (and gay by nature), Visconti, who began his film career as assistant to the great French film maker Jean Renior, started his career in the informal Neo-realist tradition and ended up embracing a very formal style related to the theater and opera mediums in which he also worked and excelled.

The remarkable thing is that he created memorable films every step of the way. From his debut in 1943, Ossessione, to his finale, 1977’s The Innocent, he was a memorable film maker and Criterion has noted this, placing 1954’s Senso, 1957’s Le Notte Bianchi, and 1963’s stunning The Leopard in The Collection. Though Visconti wasn’t unduly prolific, there are still several of his films which could profitably be placed alongside these pictures. One of the front runners would be Rocco and His Brothers.

Running an epic three hours (in its full director’s cut, for there are lesser ones around), and taken from a section of a novel by Italian writer Giovanni Testori, Rocco tells the story of the title characters, peasant siblings who moved from southern Italy to northern and industrial Milan with their mother, following the death of their patriarch, in search of a better life.

Sad to say, while some will end up better than others, the family that was will largely dissolve in the big city. The oldest brother will marry and turn away from the family. Three of the others will engage, at least for a time, in the boxing game. Two of them will love the same woman, a beautiful but troubled prostitute. Due to this, one will come to a tragic end. Two will decide to return to their roots in the south.

The cast is one of Visconti’s finest. Yes, the so-handsome-he’s-pretty Alain Delon is more image than acting in the title role (and Visconti was always a sucker for a handsome face, sad to say), but the cast also includes Renato Salvatori, Katina Paxinou, a young Claudia Cardinale (she and Delon would return to star to better effect in The Leopard), and, especially, Annie Giradot as the ill fated prostitute.

The cinematography of Giuseppe Rotunno, the music of the sublime Nino Rota, and the matchless direction by Visconti, not to mention his own novel-like screenplay, helped Rocco to emerge as one of the great films of the day (and later). Lately, its been restored to a wonderful condition and given a fine DVD treatment (not by Criterion). However, shouldn’t it one day come to its true home, The Criterion Collection?

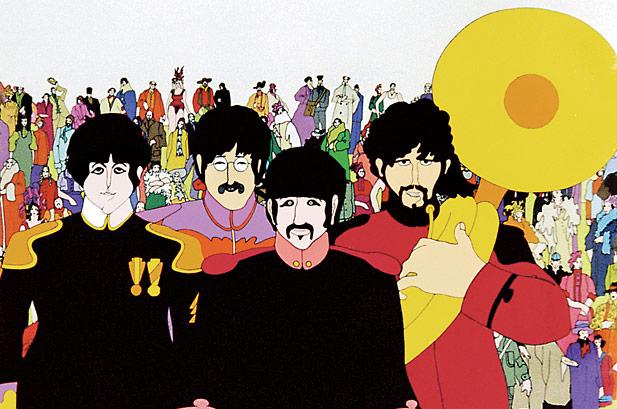

5. The Yellow Submarine (1968)

Usually, rock music and film mix uneasily. Not counting documentary/concert films, made for admittedly specialized tastes, its hard for film to capture the live immediate spark of a good rock concert/event.

Somehow, trying to put singer/musicans in a dramatic context either seems to drain their powers or makes them look awkward (save for 1965’s memorable documentary Don’t Look Back, the renowned Bob Dylan’s film career could be a working example of this). The Beatles, those spritely turned profound game changers in the music world, also turned out to be exceptions to the rule cinematically, if in a limited fashion.

Many think of the Beatles film career as consisting of four films, five if one counts the TV special/short The Magical Mystery Tour (1967). First and foremost is 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night from director Richard Lester, one of the great musical films ever and a long time entry in The Collection. Then, the next year brought Help! (again directed by Lester), a silly James Bond-esque spoof with a greater score than even its renowned predecessor.

Last and least was 1970’s Let It Be, a TV documentary special turned into a feature due to contractual obligation issues (an Oscar winning score but the film catches the breaking up group making their last great album amidst a whole lot of bad vibes). Now that’s three, so where is four? Well, there really aren’t four but very many viewers take the subject of this entry as the fourth. Even though the film exists due to The Beatles (who only contributed a live action cameo at the end in addition to their songs)and, mainly, their revolutionary Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album, its greatness really has little to do with the group.

United Artists, the company which released The Beatles’ films, was sold on the idea of using the group’s music as the springboard for a fanciful animated feature done in the wild, loose popular style of the late 1960s. Animation, in feature films at least, up until that time usually meant the Disney way, round, cuddly, cutesy and sentimental. The overall look of this one was, to use a contemporary term, psychedelic, a veritable riot of color.

The film also inventively used such art movement modes as op, pop, and surrealism, among others, The script was also quite inventive, packing in all sorts of irreverent humor. The story, and loose it was, had Sgt. Pepper making the journey in the title vehicle to Liverpool from Pepperland, a magical kingdom existing far under the sea, but one which has been conquered by the music hating Blue Meanies, halting the lovely musical existence of the Pepperland natives.

Why did they suddenly attack? Who can say? Why did Sgt Pepper go in search of The Beatles to help? Well, ’cause they made the album. At any rate, the plot and song are the springboard for many great musical sequences (the enchanting “When I’m 64” and “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds”, which single-handedly convinced squares that rock music was full of invites to drug it up.)

The film was a hit with the public and a legend in the animation field. Until Disney reasserted itself with its modern hits starting in the 1980s, The Yellow Submarine lead the way in the animated feature film field. Just think of what Criterion could do with this film’s glorious color images and stunning soundtrack….