In 1978, the US saw the release of a book entitled The 50 Worst Movies of All Time (and How They Got That Way) by future conservative pundit Michael Medved and his cousin Randy Dreyfuss.

Though there is no point in discussing the contents of this book or its quality, the tome unleashed a tidal wave of interest in bad films and the fascination that they create in viewers. Well, yes, bad films of a certain nature can appeal to the more juvenile side of a viewer’s psyche, but, considering how many wonderful things await the discerning viewer in the cinematic world, why dwell on the bad?

While it has always been a truism that the bad outnumbers the good, logic would follow that anything that could be termed “good” would be cherished and seen and loved by the film savvy of the world. Or so one would think. Sadly, good films slip through the cracks virtually every day that comes. Why? Well, sometimes the timing of release is wrong. Sometimes, the distribution and/or advertising don’t connect with the public. Sometimes, the film is ahead of its time or the subject is not one that would ever be fodder for mass appeal.

The films listed below are worthy films that didn’t get much notice or fell by the wayside. Some did attract notice once but look to be rather forgotten now for some reason or reasons. However, by sharing these titles and a little about them, perhaps some might be stimulated to seek them out and see what they have to offer.

Remember that many films which are now thought of as great and/or beloved were virtually “dumped” in their own times and had to wait for another, more favorable season, to come into their own.

1. Make Way For Tomorrow (1938, Leo McCarey)

Careers can be funny things in any professional field, but in the movie world, they can be downright peculiar. Even by that standard, the story of director Leo McCarey was an odd one. Few careers started with so much joy. He began with the famed comedy producer Hal Roach and oversaw the creation of the major players on his lot, mainly turning Laurel and Hardy into a team.

In the sound era he created some of the best films of W.C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, Mae West, Cary Grant , Irene Dunne, and good vehicles for Harold Lloyd and Charles Laughton.

However, starting with the appallingly sentimental (if skillful) Going My Way in 1944 and The Bells of St Mary’s, its 1945 sequel (both big hits and the former a huge award magnet during the uncertain war years), his career took a bad turn ending with awful anti-Communist films such as 1952’s My Son John and, his last, 1959’s Satan Never Sleeps. How did such a thing happen? Well, the answer might lie in the fate of his purest, most unusual film, one doomed to keep the audiences away in droves.

McCarey won his first Oscar in 1938 for the Columbia released comedy classic The Awful Truth. In his acceptance speech, he thanked the Academy but said that they had rewarded him for the wrong film. Earlier that year, he had made a film which did so poorly at the box office his long time studio, Paramount, cut him loose. The film that caused the trouble was a distinct change of pace for the then comedic McCarey.

Make Way for Tomorrow tells the tale of an elderly couple who, through a series of mistakes and just plain burying their heads in the sand, lose their long time home during the bleak days of the Great Depression. With no other resources, they must rely on their grown children, who, it turns out, either can’t or won’t step up to the plate.

At the end, it’s clear that the separated by circumstances couple’s life together is over and that, whatever happens to each individually, the other won’t be a part of it. McCarey might have sugar coated this by casting stars looking to expand their range by playing “little people”.

However, he cast respected character actors Victor Moore (best known for supporting Astaire and Rogers in several of their films), Beulah Bondi (an Oscar nominated actress who was then only 46 but looked quite convincing) , Thomas Mitchell, Faye Bainter (both of whom would win Oscars within two years of making the film) and other below the title names. He might well have softened the ending, but he wouldn’t compromise.

Now, if he had just made a harsh, slice of life film, this would be an interesting outlier in both his career and in the Hollywood production of that day but this is more than that. The great French director Jean Renoir, who lived and worked in Hollywood for some years, once said that McCarey was among the best of directors because he “understood people”.

No better proof of that exists than this film. The old couple is highly sympathetic but they aren’t saints. Neither tries to the greatest degree to assimilate into the home of the child that takes them in and this causes trouble for both.

Likewise, though the children are all let-downs in the end, they aren’t bad people. They may be a bit weak and all are beset by troubles common to any generation (the prosperous seeming son and his wife actually have to work hard to make ends meet with the wife giving bridge lessons for money as opposed to playing bridge all day as the mother-in-law supposes).

The villain here is just the hard cold facts of life. No less than the great Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu stated that this film was an inspiration to him (and it shows in his own work). Fine performances, a McCarey specialty, also helps out.

Paramount tried every way possible to sell this one but the public wasn’t about to buy (the Depression had started to abate but then took a downward turn again in 1938 and no one wanted realism that year). It’s a sign of how downtrodden this excellent film is that it never had a US home video release until the prestigious Criterion Collection, which often puts profit second, chose to present it.

2. Quai Des Orfevres (1947, Henri-Georges Cluzot)

French director Henri-Georges Cluzot became a sad victim of circumstance when the Nazis, having newly invaded and taken over France, exhibited his bleak and effective 1943 thriller Le Corbeau as a prime example of the French character (for those who haven’t seen it, there’s hardly a shred of decency anywhere in the little town that provides the setting).

It looked like Cluzot might be banned permanently from making films in his homeland (and he didn’t, at that point, have an international reputation) but, happily, “forever” can sometimes be far shorter than one may think. His next film came some four years later and it is a fine one. Too bad that so few really seem to know about it.

Quai Des Orfevres (the title refers to a noted police station in Paris) centers on the murder of a rich and lecherous old man. The victim was enthralled by the stage performer Marguerite, known professionally as Jenny Lamour (Suzy Delair). Her quite besotted husband Maurice (Bertrand Blier), a man from the upper classes, violently discourages the relationship, though the ambitious woman tells him the older man could advance her career.

Maurice goes to kill the man when he thinks the wife is going to an assignation with him but finds the man already dead upon arrival at the residence. A lesbian photographer, Dora (Simone Renant) in love with the performer, also claims that the woman showed up at her home the night of the killing claiming to have killed the man and needing help in retrieving the fur muff she left behind. Other clues muddy the water around the murder and crack detective Inspector Antoine (French stalwart Louis Jourvet) is put on the case.

Cluzot was never the sunniest of directors and this film is no exception but the realistically less than glamorous backstage milieu (the stage in this case being a rather second rate one) and the living environs of the characters, especially the convincing atmosphere of the police station, match up well with the mood conveyed.

Mystery (whodunit) films are among the warhorses of cinema but, in the end, this sort of film, like any other, depends on the telling. Cluzot always seemed to be a natural at this. Yes, like most films of this type, the characters are pieces in the puzzle but here they also seem like people period.

Among them are an interracial couple and the gay character mentioned and neither element is treated as a big deal, as it surely would have been in a Hollywood film of the time (and, no, the gay character isn’t denoted by inference but identifies as such and is actually treated with sympathy ultimately by the inspector).

Sometimes in Cluzot’s work one can see that it wasn’t that he was so misanthropic (though maybe he was) as looking at humanity and seeing much frailty and weakness. In the end in this film, the characters are much more sad than evil and Cluzot makes a good case that they aren’t much different from anyone else.

Being his first film back after such an unpleasant suspension didn’t help this low key picture at all. It was released in English speaking countries as Jenny Lamour and badly dubbed. Much was also made at the time of Jourvet and Delair, two performers whose screen personalities were an odd match, being in a film together. However, the point was that they were from different worlds, with the inspector inserted in hers for a time, and didn’t have that much screen time together (nor, in terms of plot, should they).

The publicity gave a rather false impression of the type of film one might see if one paid for a ticket. Sadly, this one, though it has had some exposure (it sort of comes and goes on video, which still puts it one up on other Cluzot films of the period such as Retour a la Vie and Manon, both from 1949, which seem lost to the ages), has never managed to be well known.

If a film student or fan (at least one outside of France) is given Cluzot’s name then they usually think of 1954’s famous Les Diaboliques (which has its points but isn’t among his best) and, more justly, 1953’s The Wages of Fear. Rediscovery has brought new viewers to Le Corbeau and his first film, L’Assassin Habite au 21 and even his unfinished L’Enferno (the subject of a recent documentary). Perhaps someday the faithful will dig a bit deeper and give this worthy gem its due.

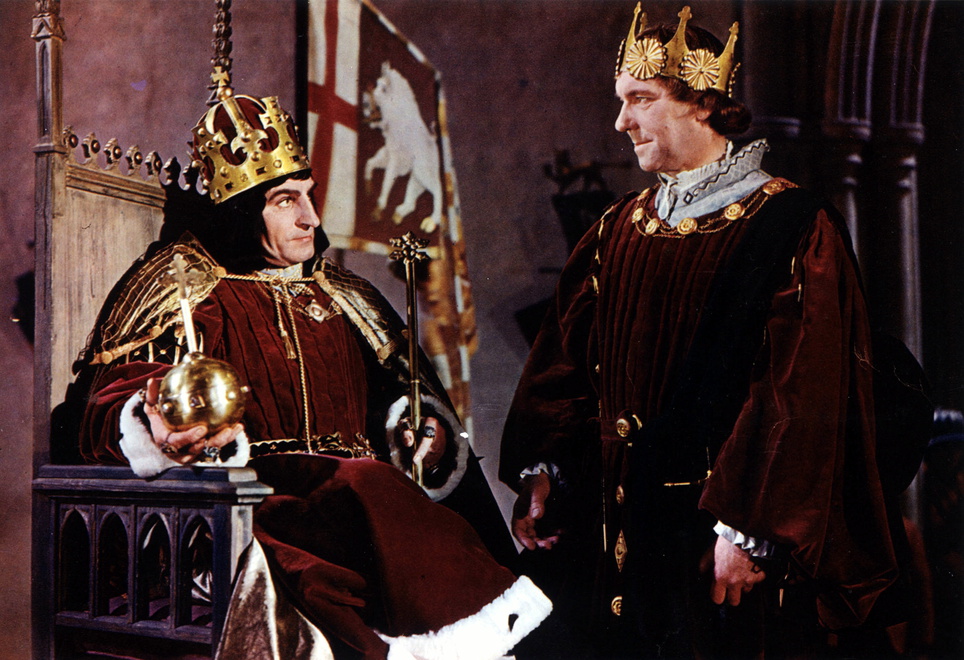

3. Richard III (1955, Laurence Olivier)

For many years, those who wish to try and measure such things insisted that Laurence Olivier was the world greatest actor. There may well have been a good case for him being the world’s finest classically trained actor and a fine all around actor per se but his was a style that was being considered old fashioned even in the later part of his career and, at any rate, how can one truly measure such things? Suffice to say, when it came to the roles and projects which were his forte, one couldn’t find a better actor for the project.

Often overlooked was the fact that he was also a rather good, if also stylistically conventional, director. He directed six films in his career, all adaptations of plays (only 1956’s The Prince and the Showgirl, from Terrence Rattigan’s The Sleeping Prince, which the actor and then wife Vivien Leigh had done in London, was a contemporary work). Of those five, four were taken from the works of Shakespeare, of which Olivier was considered the foremost interpreter in his time. (The odd man out was 1972’s The Three Sisters, from Anton Chekov and his last directorial work.)

Of those four, 1965’s Othello, blessed with fine acting but cursed with an almost non-existent budget, is surely the least. That leaves the other three. His directorial debut was the rousing war-time film Henry V (1945), a wonderfully colorful and inventive film that delights the mind and eye of even those who don’t like the Bard (Olivier admitted it had a “juvenile charm”).

Hamlet (1948) was done in black and white and the cinematography would do a film noir proud (and the field of depth in the film was incredible). Though many noted that the play was much abridged, the production was a big success and won Oscars for, among others, Olivier’s acting and the production itself. With hits such as those, it would seem like Olivier was on a role and would follow them up right away with another such triumph. Or so one would think.

Olivier actually got back to his theatrical roots after Hamlet and was more interested in the stage than film. Aside from 1952’s Carrie (actually filmed two years earlier but held back for release by an uncertain studio) and 1953’s fine but little seen The Beggar’s Opera (from his stage version), he wasn’t seen on film during the first half of the 1950s.

Then he decided to commit his version of the villainous Richard III to film. Once again Olivier used color and, this time out, widescreen (Vista Vision). However, unlike Henry V, which looks like a cross between a storybook and an idealized stage production, this film creates a stunning Medieval Book of Hours look, which is quite correct for this tale from British royal history. The costumes and sets are first rate in a stylized way which complements the structure.

While the casts of the first two films Olivier directed were quite good (more so for the first than second), the players in this film topped them both with the likes of John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Claire Bloom, Stanley Baker, Sir Cedric Hardwicke and many others included. However, no one could best Olivier himself in this film.

Heavily made up to resemble the infamously deformed Richard III, the character tells the viewer at the start that he is determined to prove a villain and he most certainly makes good on that promise. He is the spark that animates this film and gives it a life force not quite there with the first two. Some think this is Olivier’s best screen performance and the best of his directorial efforts. Why, then, is it overlooked?

When Olivier was about to launch the film he was talked into what, in hindsight, was not a good decision. Since Shakespeare is iffy at best at the box office, someone had a bright idea of showing the film on NBC TV in the US…the same day the film was to open in theaters! The idea seemed to be that if the public liked what they saw on TV, they’d pay to see it again in a theater (this was the era when film versions of TV plays were finding success but this wasn’t quite the same thing).

The TV censor shorn the film of a number of violent shots (which had to be restored years later) and only the very select few with color sets at the time could see the film’s glorious multi-hued cinematography, so it was felt that this “sampler” would surely entice the multitudes to the actual theater. This trick has been tried since, though not until the pay-per-view age again, and has never worked. Each and every time it has killed the film at the box office (this ploy makes it seem as if the film was damaged goods in some way).

When the Oscar nominations for that year came out, only Olivier’s performance got noticed. Though he did have worthy competition in Kirk Douglas’ work as Van Gough in Lust for Life, both sadly lost out to Yul Brynner in The King and I. Olivier seems to be out of fashion now but, if and when his time comes again, the one should be top of the list for rediscovery.

4. The Wrong Man (1956, Alfred Hitchcock)

For all the serious, serious scholarly works on the oeuvre of Alfred Hitchcock, it must be admitted that, in the end, he is, and always was, thought of as a fun film maker. Of course if one can sugar coat serious themes to the point where they can be fed to a not only unsuspecting but willing audience, then so much the better.

However, there are a few anomalies in the Master’s filmography, films that show that he was still interested in growing beyond his established formula. 1948’s Rope and 1949’s Under Capricorn both broke with the principals of montage on which Hitchcock had based his famous style and the later film was a very rare costume drama to boot (and the results both times show why he never went down those paths again).

At points during the 1950s he looked to be trying to incorporate what might be termed more legitimate drama into his films as well. Though it was a suspense thriller in form 1953’s I Confess was also a character study of a priest who can’t reveal details of a crime due to the seal of the confessional (and was the rare film to explore Hitchcock’s Catholic roots).

However, due to a number of factors, this film didn’t come off terribly well. Three years later, Hitchcock tried even more overtly to be “serious” and that film was the interesting and well made The Wrong Man.

From the outset this film announces that it will be different from the run of Hitchcock films. A fun game the film maker played with the audience throughout his career was the insertion of himself into the film in a walk-on cameo. His general rule was that the more serious the film, the earlier the cameo would occur.

This time there is no hide and seek with the viewer. Hitchcock appears in silhouette on a darkened street set and, for the only time on film, speaks and speaks to the viewer, informing that the following is a true story, again for the only time in a Hitchcock film.

The action then cuts to a very real New York City nightclub (The Stork Club) late in the evening. A title card informs the viewer that this day, January 14, 1953, would be one that the main character, Christopher Emmanuel “Manny” Balestrero (played by Henry Fonda), a musician working in the club, would ever forget. After finishing a long day of work, he goes to his bank, hoping to obtain a loan for some much needed dental work. However, while there, a bank teller fingers him as the man who robbed the bank a few days before!

Nightmarishly, others join in tagging the man for, not just that robbery, but other crimes the same man supposedly committed. Little by little, all the means by which Manny might prove his innocence seem to vanish. Even worse, his loving but fragile wife Rose (Vera Miles) starts to crack up under the pressure and ends up institutionalized.

Throughout his career, Hitchcock had used a “wrong man” theme for a number of successful films, starting with his big international breakthrough The Thirty Nine Steps (1935) and, three years after the film under discussion, one of his biggest hits, North by Northwest (1959). However, there is a big difference in those films and this one.

In the world of North by Northwest, movie star handsome ad exec Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) could be framed for a murder in the lobby of the U.N. and still run out of the building, into a waiting, ask-no-questions cab, and get to the train station unfettered! No such super-hero antics are present in this film.

The character’s arrest and imprisonment ring all too true. Also, no major star actor was ever better at portraying the common man than Henry Fonda (and this would be his only film with Hitchcock). Much of the power of the film comes from the surety that this is a dire situation for the man and his wife and, no matter how it comes out, will leave scars for them to deal with ever after. (The real Balestrero was financially crushed by this episode for the remainder of his life and his wife’s recovery was very delicate.)

Special mention must go to Miles, who renders one of the most memorable performances ever to grace a Hitchcock film and also one of the most unusual. (Hitchcock famously put her under personal contract, with an eye towards making her a star with 1958’s Vertigo but pregnancy and self-possession de-railed those plans.)

In the end, this film got some good reviews but it wasn’t at all what the public wanted from a Hitchcock film and wasn’t willing to gamble along with him in this change of pace. That’s too bad, for it does show that he was more than just “the funny little man who made the mystery (sic) films that he showed up in someplace”, as time and good taste have since proven.

5. The Cranes are Flying (1957, Mikhail Kalatozov)

In recent years Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov has become well known in the film studies community as a great visual stylist. This reputation is mostly based on 1963’s I Am Cuba (appalling jingoistic but stunning to look at) and a once overlooked rediscovery, 1959’s The Letter Never Sent (also great to look at). Kalatozov had a very odd stop-and-start career in the Soviet Union and not due to the usual reason of government suppression, at least not in the traditional sense.

He was actually well placed in the government and spent many years in the film culture ministry, serving in both the Soviet Union and a branch office in Los Angeles. Therefore, he filmography is a bit limited and much of it contains uninspired films made to order for the government (which might be true of I Am Cuba as well, but the island nation seemed to stir his creativity).

For many years he was known to film students and international film fans for his early effort Salt of Svanetia (1930) and the film under discussion, which was an art house staple for years but now seems to have gone by the wayside.

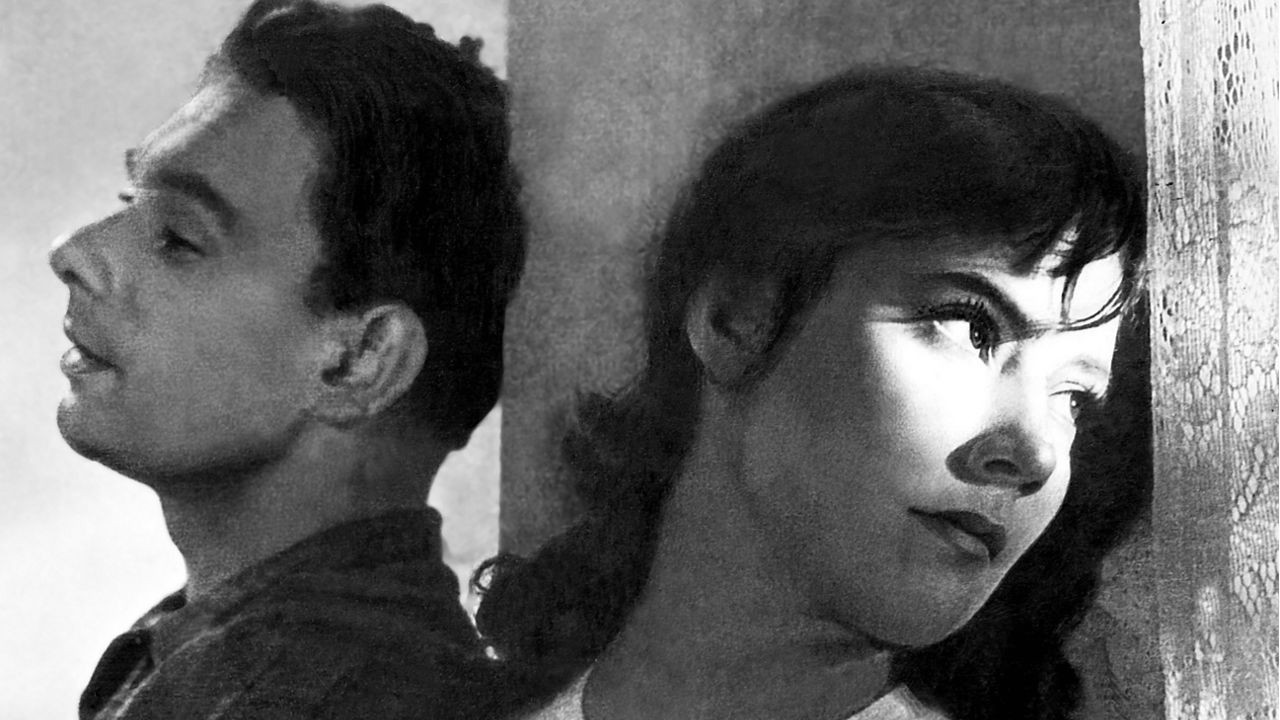

The Cranes are Flying is both a tragic love story and the more inspiring story of living on after tragedy. In the early days of World War II lovely Veronica (Tatyana Samoylova) and patriotic Boris (Aleksey Batalov) swear their endless love under a flock of cranes magnificently flying past. However, Boris feels the need to do his duty and goes to the front without telling Veronica of his decision.

Though the two meant their vow, larger events will take precedent. Boris will disappear from Veronica’s life, though she will keep hoping for his return. Unfortunately, the course of the war will also alter the shape of her life as circumstances caused by the greater conflict will intrude to change the course of Veronica’s fate permanently.

Those looking for the director’s great visual style won’t be disappointed by this one. Just a cursory look shows that he knows how to use the camera and how to tell his story with complex and appropriate angles, cuts, and shot set-ups.

However, there is also a beating heart at the center of this film, courtesy of its main player, Miss Samoylova. She was a great-niece of the famed and influential drama teacher Constantin Stanislavski. She may well have used his teachings since she was a fine actress (and a most attractive one as well). She was invited to work in Hollywood and other places outside of the Soviet Union but was forced to turn those offers down by the government. Sadly, her only other big role was in an acclaimed 1967 Soviet adaptation of Anna Karenina.

As for the film itself, the government didn’t care for it (not a great surprise, given the history of films in that country) but it wasn’t banned and the public loved it both domestically and in art houses around the world. To this day it is the only Soviet film to win the Palm D’Or at Cannes. Given all of that this film has going for it, it seems rather forgotten now. This may well be part of a backlash against the traditionally acclaimed art house films of the past.

I Am Cuba and The Letter Never Sent are discoveries of a new film generations. The Cranes are Flying is in the textbooks of university film courses. However, if that is that case, the known and proven old shouldn’t be overlooked simply because it isn’t the newest thing. There is still a lot of artistic life in The Cranes are Flying.