When watching a film, we progress with the characters, the story, the plot, or whatever is gripping you to film. Sometimes, the mood or atmosphere or camera work or choice of music or many other creative choices holds you locked into that particular experience instead. However, the most accessible way is through character and story, until something occurs that shifts it all.

Just when you are immersed enough in film, something happens that alters the entire course and you might say yourself ‘Did I miss something?’. The answer is no, films can change course whenever the filmmaker wants it to and not just a character or story choice progression or arc. Therefore, on this list, you won’t see scenes where there is a major plot twist or the character progress on with their desired life, goals, etc.

Sometimes a scene in a film alters everything, the entire film changes tone or rhythm, a character invalidates everything he or she has been doing and goes against their beliefs, a scene that contradicts everything we’ve just seen beforehand, and some scenes challenge the actual form of filmmaking.

1. Ordet (1955)

One might point out the end scene that is truly on the most remarkable spiritual, transcendental, or religious moments captured on film. Leading up to the end, we have spent about two hours with the characters of the Borgen family that include Mikkel who has no faith, Johannes, who thinks he is Jesus, and Anders who loves the daughter of pastor from another religion. All fall under the jurisdiction of the father, Morten, a widower and pastor. Despite all the set up, one can immediately grasp that all the family members have diverse views on religion and more importantly faith, in which 1920s Denmark meant a very strict way of life

As the film progress with religious, family, and societal clashes in one of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s masterpieces, we arrive at the end funeral scene of Inger, Mikkel’s wife. After continuous debates on faith, Johannes believes Inger can resurrect from her death. And in a stunning moment of beyond realization and continually blinking your eyes, you are actually seeing Inger awake in the coffin to everyone’s amazement.

This film is grounded in faith and what it means to each of the characters we’ve spent two hours with. However, not only from an audience point of view but all the characters will have their faith shaken after this moment. Is Johannes the second coming of Jesus Christ? Will Mikkel have faith? Where will Borgen’s faith lie? What will Anders now believe in? The end of Dreyer’s film leaves all the characters and the audience questioning the true aspect of faith.

2. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

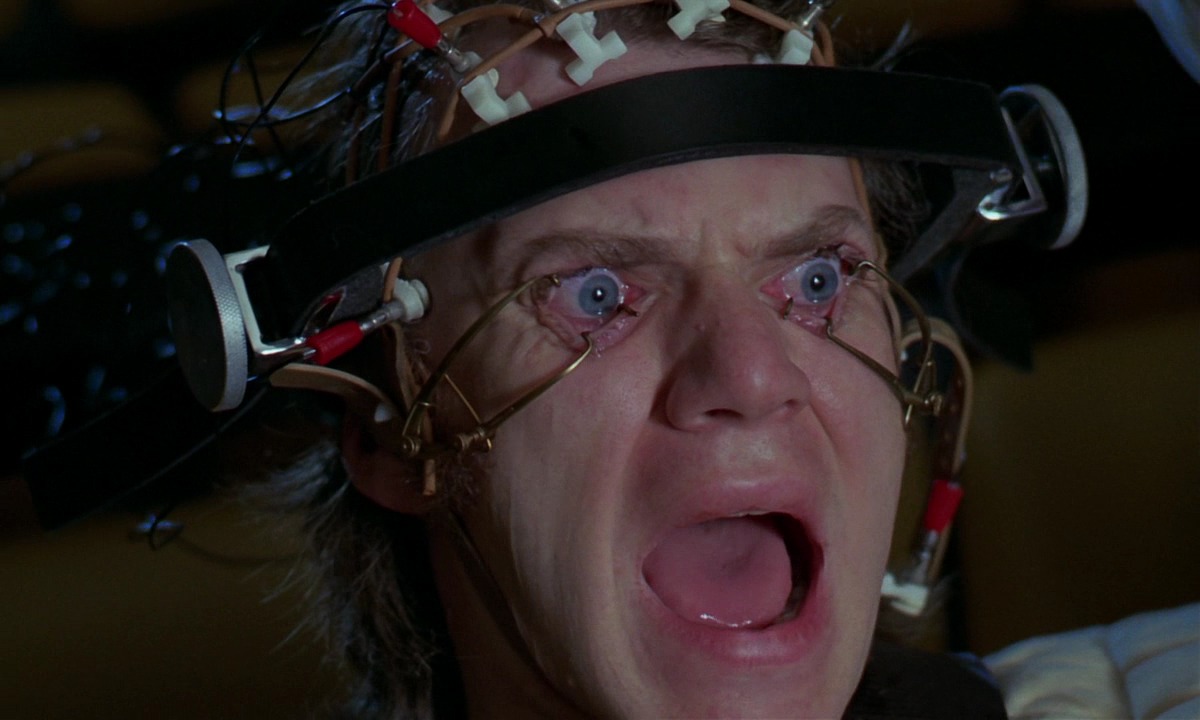

Many things can be said about Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian nightmare where we the witness the misdoings and ultimate attempted correction of the unpredictable Alex DeLarge. Throughout the whole film, the audience is sucked into the wild world of this character and his fellows droogs of a roll coaster of rape, ultra violence, and of course, Beethoven. It is these things that lead to the epic conclusion of Alex’s journey.

Most films try to have one memorable scene, as in any Kubrick film really, it is hard to pick just one. But here, we can boil it down to one scene that can alter the entire justification of the film. One can spilt the film in two parts, the first part where we experience Alex’s doings of a rebel, anarchist, delinquent and many other forms of the definition in society and the second part being his imprisonment and scientific experiments to change his ways as he heads back into society.

In the scene leading up to his hospital visit, where his actions led to the consequence of being inflicted violence and Beethoven onto him, leading to a suicide or breakout attempt, the film leads to the conclusion.

As it appears to be from the smiles, the scientists, and the media, Alex has actually been cured from criminality so to speak. But it is the final image and voice over where ‘I was cured all right’ while Alex fro-licks with a naked woman on top of him in pure white, innocent snow surrounded by a circus of aristocrats nodding along proves the entire second half of the film is up to interpretation.

Was Alex playing the game all along? Was he just waiting to be freed? Did he just have a moment of realization? Is Kubrick just messing with our heads or going against the novel? The last line and image makes you think about what Alex really think.

3. 35 Shots of Rum (2008)

The one scene here might actually be a cheat but this one scene shows how all four main characters act, think, and progress differently after the action. This isn’t just a story or character progression but the entire progression of characters change along with the tone of the film. Claire Denis has the power to show how cinematic moments can be through gestures, dance, action and almost no dialogue. In her film here, she creates a stunning scene of just that where all four main characters are changed and act differently towards one another.

About midway through the film, Lionel, Josephine, Gabrielle, and Noe miss a concert and stay in a bar while it down pours outside. Music starts to play and all four begin to dance, amongst one another and flirt and move in a most sensual way that is disapproving to the on lookers.

No words are spoken but just music and dance that resembles the best of any non-choreography that reveals the hidden maybe drunken true intentions, desires, and inner selves of the characters. But it is after this scene, the film drifts away from the lighter, family bond and observance of particularly Lionel and Josephine to a more sober self reflected, more confrontational and inevitable change of the all involved in that bar that one very night.

4. Close-Up (1990)

Several of Abbas Kiarostami films can be on this list such as when we see the camera and crew at the end of ‘Taste of Cherry’ or the scene where the two strangers might actually be husband and wife in ‘Certified Copy’. Yet it’s Kiarostami’s mix of documentary, fiction, re-enactment, and of a film that stands out amongst the rest.

This work tells, shows, and deals with the somewhat aftermath of how a man, Hossain Sabzian, impersonated a famous Iranian director, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, to a middle class family. The film is told through re-enactments, interviews and some scenes that are just so immersed in the world, it’s hard to decipher such as this one scene that can change the entire film. Sabzian and the real life family and judge re-enacted scenes for this film since Kiarostami immediately jumped at the rights while the actual events of the film were being played out in real time.

This is what makes the film so unique because as you watch it for the first or fifth time, you truly don’t know what is real or not. This leads to the only confrontation between the two towards the end makes you question as the camera is far away, shot in a long lens as the audio feed cuts in and out.

What is real and what is fiction? Is this scene staged, captured in real time, re-acted like many scenes before it? In the end, one cannot ignore the powerful emotional content of the scene and the two involved no matter how and why is was filmed the way it was.

5. Hunger (2008)

In one of finest film debuts of all time by artist turned filmmaker Steve McQueen, he explores the the events of leading up to the 1981 Irish hunger strike in prison led by Bobby Sands. From the beginning of the film, one can tell McQueen and co-writer Enda Walsh are challenging the narrative of the filmmaking progress.

We spend a fair amount of time with a prison guard and another IRA prisoner before Bobby Sands literally comes bursting and beamingly onto the screen, ferociously and dedicatedly in the upmost conviction by Michael Fassbender. However, the brutal, stark, sound induced, and mostly silent poem of a film leads to one explosive scene.

Much of the film is told through sound and image up to this point where we see Sands enter a room to talk to a Father Moran, fantastically performed by Liam Cunningham. What we experience here is almost theatrical mini film, where after so much silence and the story being told without dialogue, is an uninterrupted, 17 minute static shot of the two in the most engaging dialogue involving politics, morality, religion, and what it means to be a human being standing for a cause.

Then we got an 8 minute shot on Fassbender continuing the conversation before a final cut away to Cunningham for a total of 24 explosive dialogue in a roughly silent film.

One can ask why McQueen told the film the way he did up to this point. Did he allow us to escape the visceral and raw visual poem that was taking place before out eyes for a relevant one on one conversation? After this scene, an audience member must re-access everything they have experienced after Bobby Sands and Father Moran touched so many themes in just one tiny space.