5. The Innocents

Keeping the faith during wartime, after witnessing the worst humanity has to offer, seems at times impossible. How can you still believe in God, certainly in his protective might, after having endured so much cruelty and horrors, after countless innocent lives were swept away by great waves of evil? Anne Fontaine’s soulful and historically important film, “The Innocents,” doesn’t really have a definitive answer to this, and even the pious characters of the film seem to be at a loss.

The film, partly based on the experiences of Madeleine Pauliac as a Red Cross doctor during World War II – also the aunt of Fontaine – as well as the massive rape of Polish women during Soviet occupation. Taking place in 1945, shortly after the end of the war, a Polish nun, Sister Maria (Agata Buzek) pleads for a help in a Red Cross encampment. At first she’s bluntly dismissed since the encampment only provides medical care to the French, but one doctor, Mathilde (Lou de Laage) takes pity on her and follows her to the convent, where one of her sisters is apparently gravely ill.

It turns out that the ailing nun, alongside six others, are pregnant after being routinely violated by Soviet soldiers. In order to protect the convent from shame and scandal, the head of the convent, Mother Superior (Agata Kulesza) wants to keep it a secret. But as the lives of both the nuns and their babies are at stake, Mathilde is accepted into the fold and soon begins to appreciate their lifestyle and choices, despite her own anti-theistic and communist sensibilities.

Like many great films dealing with religion, the film also shows the danger of religious idolatry, as the fear of sin and scandal leads to a shocking discovery. It also exposes the horrific psychological and physical abuse of women during wartime as well as within the Catholic hierarchy. These women are continuously subjugated and told to feel shame about their bodies. It shows how many women didn’t have many choices in these dark days, and joined the convent out of a lack of options.

It’s not often you have a World War II film from the perspective of women, suppressed by religious traditions as well as the threat of violence. Aside from its historical significance, it also has one of the most profound analogies of faith I’ve ever heard on cinema: “At first, we’re like a child that his father holds by his hand, who feels safe. A moment comes and I think he always comes where the father will let you go. We’re lost, alone in the dark. We call, nobody answers. We’re getting ready, we’re surprised. We’re hit in the heart. That’s the cross. Behind all joy, there is the cross…”

It’s honest and heartfelt. God can be many things for many people, but if there’s one thing he’s known for, it’s his silence. Some women in this film seek their independence, and one even leaves the convent to pursue a different life. Others stay to do God’s work, despite having enough reason to be resentful for his apparent absence. Their troubled lives have given them more than enough justification for apostasy, yet they still believe some transcendent reward awaits them in there hereafter.

And as the film ends on a beautiful note, you can’t help but admire these women and think about the real women of the past, often forgotten about and ignored in history. This is their cinematic tribute and I’m grateful for having seen it.

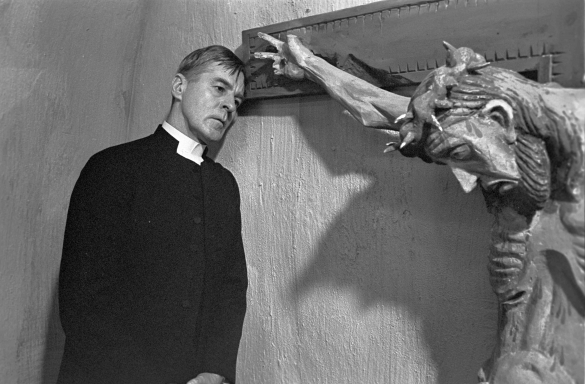

4. Calvary

The awful truth is that, even after the most symbolic sacrifice of all, the suffering that comes from crucifiction, the bruised and beaten messiah carrying the wooden cross, blood seeping from the thorns penetrating the scalp, the slow and agonizing walk of death, the deliverance of a merciful death, the talk of resurrection, life simply goes on.

In all its seediness and sin, the people continued on as if nothing happened, as if nothing had changed, as if no lessons were learned. If Christ would look at history, he would see organizations and politicians abusing his words for power and financial gain. It would almost seem like he died for nothing. How many people were really saved? Does it match the amounts of people that suffered, spiritually or physically, in their own deluded hands or by the hands of others in his holy name?

Even now, even after all the apparent injustices, the suffering and death of so many innocents and the obliviousness of corruption in governments, life goes on. Policies aren’t changed. Things go on as before. The horrors of human nature continue on.

And yet you mustn’t lose hope. You must continue his example. This is what Father James Lavelle (Brendan Gleeson) does, serving as a spiritual confidante in a small town in Ireland where most of its parishioners have long given up on the Church and its message. As the opening of the film suggests, it’s understandable, especially after all the revelations child abuse and the conspiracy of the Church in hiding it. This is a church that has essentially failed its flock and its Messiah.

But throughout the film, Lavelle continues to visit each flawed parishioner, from a cynical banker (Dylan Moran), a suicidal writer (M. Emmet Walsh), an unfaithful spouse (Orla O’Rourke) and her disinterested husband (Chris O’Dowd), a nihilistic doctor (Aidan Gillen) and more, hoping to offer them some spiritual guidance. Most of these parishioners reject or dismiss his presence, but Father Lavelle never gives up hope on any of them.

But the dark aftermath of the scandals leaves Father Lavelle in possible mortal danger, with a mysterious stranger in a confessional threatening to murder Lavelle the following Sunday. This mysterious stranger had been abused by a different priest and hopes that the death of a good priest, Father Lavelle, will leave a necessary impact.

In other words, the death of an innocent will hopefully shake up the sinful order of the Catholic Church. While Lavelle ponders his decision to either flee or face the stranger, he also rekindles his bond with his estranged daughter (Kelly Reilly), and in that most wonderful scene, he stresses that the virtue of forgiveness has been seriously underrated in Church doctrine.

John Michael McDonagh’s masterpiece is at times a brutal dark comedy, especially with his flair for witty dialog (which runs in the family, as is evident by his brother Martin). But it’s also a spiritually profound drama that asks hard questions about the Church’s culpability in the scandals, and what it means to be a good man in a world filled with morose sin. While some might find Lavelle’s final decision ridiculous, others might grasp its spiritual significance.

And while life goes on at the end with its many parishioners continuing on their sinful ways, the ones who have been touched by Lavelle’s presence move forward toward a more fulfilling life. All we can hope now is that people like Lavelle, even after their tragic deaths, will receive their divine rewards.

3. Winter Light

Jonas (Max von Sydow), a fisherman in a small rural village in Sweden, has become obsessed with the prospect of nuclear annihilation. He reads about the Chinese people, how they are raised to hate the West, how they they will one day acquire nuclear capabilities; one has to remember that this was film was made in the early 1960s.

Despite having three kids and an adoring wife (Gunnel Lindblom), he grows increasingly despondent. His wife urges him to speak to the local pastor, Tomas (Gunnar Björnstrand), and though Jonas doesn’t see the point, he eventually agrees.

But something is amiss with Pastor Tomas. The pastor seems sick and weary, and he looks like he’s in dire need of rest. He doesn’t seem to be up to the task of consoling Jonas, but he tries anyway. But when Jonas asks him the simple and heartfelt question, “Why do we have to go on living?” the pastor doesn’t know what to say.

Without wanting to embarrass the pastor, a disappointed Jonas states that the pastor isn’t feeling well and that he shouldn’t bother him. The pastor nonetheless urges him to meet him later. When Jonas and his wife leave, the pastor begins to grapple with his own depression and existential anguish, something that has been brewing inside him for a long time. Will the pastor find the right words to save Jonas from his suicidal urges?

Despite my opening with Jonas, the film is centered solely around the pastor and his spiritual struggle. It’s a character piece that takes place in a short space of time, from morning to afternoon. But in this short time, so many things are pondered and revealed. It’s not just about a pastor who has lost his faith – it’s also about a pastor mourning his late wife. It’s about unrequited love, about loving someone who can’t love you back; in this case, it’s the schoolteacher Märta (Ingrid Thulin) and her affections for Pastor Tomas.

Perhaps it’s even about the irredeemably of the human race, especially with the creation of the atomic bomb. We were always adept with extinguishing life, and now we have the ability to extinguish all life on earth. Is this what Christ struggled and died for?

Director/writer Ingmar Bergman had a complicated relationship with his father, a strict Lutheran minister. As all of his films are deeply personal, perhaps the voice of his pious father is speaking through these films, through Bergman’s own doubt about the existence of God. Like Pastor Tomas, Bergman desperately wants to believe. He wants to be able to bask in God’s glory. But he cannot give up his reason, the inconsistencies of scripture. He cannot deny the existence of evil nor God’s silence.

“Winter Light” is known as the second film an official trilogy, starting with “Through a Glass Darkly” and ending with “The Silence.” All three deal with themes of faith and spirituality. Like all of Bergman’s wonderful and erudite filmography, it’s a film that refuses to comfort the audience with easy answers. If the answers he does eventually present are agonizing to the soul, then so be it.

Bergman is an artist who just wants to be true to himself and doesn’t want to lie and pander to his audience. The ending of “Winter Light” is both hopeful and tragic. It ends in the beginning of the next service, with Pastor Tomas proclaiming, “Holy, holy, holy, the world is filled with his glory,” with Märta being the only one to have shown up for his service.

The words at the end might ring hollow, knowing what Pastor Tomas truly believes, yet he stands there anyway. He continues on the charade. Atheist philosopher Sam Harris mentioned that he has received great many correspondence from religious authorities who have lost their faith but still continue on. Even Mother Teresa – though my own feelings concerning her divinity are not very positive – suffered fierce periods of doubt throughout her life.

As Pastor Tomas stated so dispassionately to Jonas earlier in the film, “We must carry on.” Sometimes it’s as simple as that. If you do so, perhaps you will feel glory again, if only for that brief moment.

2. The Mission

The Angelical Newspaper appropriately (and rather unimaginatively) titled Church Times awarded Roland Joffe’s “The Mission” the number one spot on their list of the top 50 religious films. If that wasn’t prestigious enough for you, “The Mission” was also one of 45 films selected by the Vatican on their list of films celebrating the 100th anniversary cinema, placed under the topic of religion. And in my humble opinion, it’s not just one of finest examples of religious cinema, but also one the most beautiful films ever made.

For all its biblical splendor, it’s mercilessly honest about the mortal sins that accompanied the Catholic Church’s reign. It refuses to shy away from the violent atrocities of both the Portuguese and Spanish colonialists while they were under the moral protection of the Catholic Church.

The film details one of the many crimes against the indigenous people, in this case the Guarani community from Argentina in 1740. Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons) manages to be accepted by this community and build his mission tribe inside their jungle.

Meanwhile, a man dealing in the slave trade of these natives, Rodrigo Mendoza (Robert de Niro), is seeking salvation after killing his brother Felipe (Aidan Quinn) in a fit of jealous rage. Father Gabriel offers him the possibility of redemption, if he joins him and his fellow Jesuits (which includes Liam Neeson by the way) on their return journey to the mission. Rodrigo does indeed find salvation in the loving hands of the Guarani community.

But peace will not last as the Treaty of Madrid is signed, which puts the Guarani tribes in danger of becoming subjects for Portuguese colonialists…

Despite the inevitable violence and tragedy at the end, it’s certainly not all miserable. It’s a film that also revels at the majesty of God’s creation – evoked most wonderfully with its beautiful scenery, accompanied by one of the most beautiful soundtracks ever composed by none other than the great Ennio Morricone.

The scene in which Rodrigo retrieves his redemption will stay with you, a great reminder of the power of love and the light that religion can offer. Aside from condemning the religious authorities at the end, the film does celebrate the individual Jesuits who went against their order to protect (and die among) their converted tribe. It’s a sacrifice worthy in the name of Christ himself. It shows us what fighting for a higher power truly means. It ends on the most appropriate Bible quote: “The light shineth in the darkness and the darkness hath not overcome it.”

1. The Apostle

One of the greatest gems of religious cinema is Robert Duvall’s passion project “The Apostle,” a film he both wrote, directed and starred in. He had spent decades trying to get funding for this film and was eventually forced to finance the film himself – though it needs to be said that due to the film’s success, all his money was reimbursed by the distributors. The passion and accuracy, both in its depiction of Pentecostal Christianity and Southern culture, is evident throughout the film.

It celebrates the spirit of these preachers without reverting them to stereotypes or insidious charlatans. They are lyrical in their poetic scripture; they move as if possessed by the Holy Ghost himself. They bring maddening joy to their congregation, which, to people who are used to sombre church services, like me, can seem rather shocking in comparison.

But it also dares to expose the innate prejudices of small rural Louisiana. The ghosts of the Confederacy and its tired mission, still haunting the plains and uneducated men. It shows that these preachers, despite their divine calling and selfless sincerity, are people as well. People with the same capability of sin like everyone else.

Sonny (Robert Duvall) is such a preacher, a man who is routinely unfaithful to his wife (Farrah Fawcett). Despite this, there’s no question regarding his faith. This is a man who verbally speaks to God as if he’s always alongside him. With little regard to his neighbors, he also unleashes his frustration to them when his life begins to fall apart.

When his wife leaves him for a younger preacher, Sonny lashes out violently and beats the young preacher with a baseball bat, which eventually kills him. Instead of facing up to his crime, Sonny flees, and for awhile, aimlessly traverses Southern Americana. Eventually he finds himself in a racially segregated town in the Bayou. He takes over a Black church from a retired preacher and hopes to find redemption by ending racial segregation and bringing people together.

All of the characters feel accurate, even if they are played by famous people like June Carter Cash and Billy Bob Thornton. Duvall had long been an admirer of Pentecostal culture and wanted to make a tribute to the inspiring preachers he’d seen on stage – if you want to know more about this, I’d suggest watching a very interesting interview he did to promote the film with Larry King, which you can find on YouTube. But he doesn’t portray these preachers with excessive grandeur – he just lets them be who they are. They just want to spread the word. They want to give people access to the gates of paradise.

Their hearts are in the right place, but even so, it doesn’t mean that they can’t be led astray just like any creature of God. The film ends on a touching note, without reverting to typical Hollywood sentiment. It ends with a good man paying for his sins. But even with his freedom gone, he’s still spreading the word.

One hopes that when his time comes, God will think he’s done enough so he can finally come home…