A film that runs longer than five hours is certainly a rarity. Commercial films with wide releases usually are between 90 and 130 minutes long. Fictional movies longer than that are generally blockbusters with big budgets that need enough time to fit in many actors and spectacular scenes; this applies to both contemporary big movies (the recent “Avengers: Infinity War” clocks in at 149 minutes), and older ones, like the great epic, often historical films from the middle of the 20th century (for example, 1963’s “Cleopatra” was 248 minutes long).

More often, works that run over two or three hours are auteur films and get such a length because of pure artistic reasons. Slow-paced films is characteristic of many great filmmakers, from Tarkovsky to Ozu.

When the film goes over four hours, a very strong decision is made by the filmmaker, and even more so when the length surpasses five hours, as we will see in this list. Such long films make for a difficult watch, but have the enormous advantage of immersing the viewer in the story in a way that shorter films cannot do.

At the risk of losing more casual viewers, five-hour long films make a strong statement from the filmmaker, who evidently believes in their work so much that they feel okay with asking a considerable amount of attention from the public. With this list, we will see the reasons some filmmakers made such a decision, which can be appreciated or not, but is certainly impressive.

The list is in chronological order.

1. Napoleon

“Napoleon” by Abel Gance is one of the great masterpieces of early cinema. It was made in 1927, and to this day is admired and studied for its experimentation with film techniques seldom used before. It stands with the works of D.W. Griffith as one of the first films to move away from still shots in order to experiment with editing and moving cameras.

It is a film of extreme ambition, and was actually only the first of a series of six pictures Gance had envisioned to tell the whole life of Napoleon. The other five were never produced, since they proved too big a project to actually realize. Later, in 1960, Gance directed “Austerlitz,” where he told another part of Napoleon’s life.

The life of “Napoleon” did not end with its initial release. Its distribution was sold to MGM after limited screenings in Europe, and was subsequently shown in the U.S. without causing much attention. The important aspect of his release is that this was a recut, much shortened version of the film.

Decades after, “Napoleon” was restored in many different versions by different editors, finally reaching a length that justifies its presence in this list. Kevin Brownlow in particular is responsible for researching and editing as most footage as possible.

The first version of the film Brownlow edited and released was in 1979, but there have been many since then, including one by Francis Ford Coppola. Additional footage found after 1979 made the film reach a length of five hours and a half, restoring de facto the grandiosity and epic nature of the film as intended by Gance.

2. Novecento

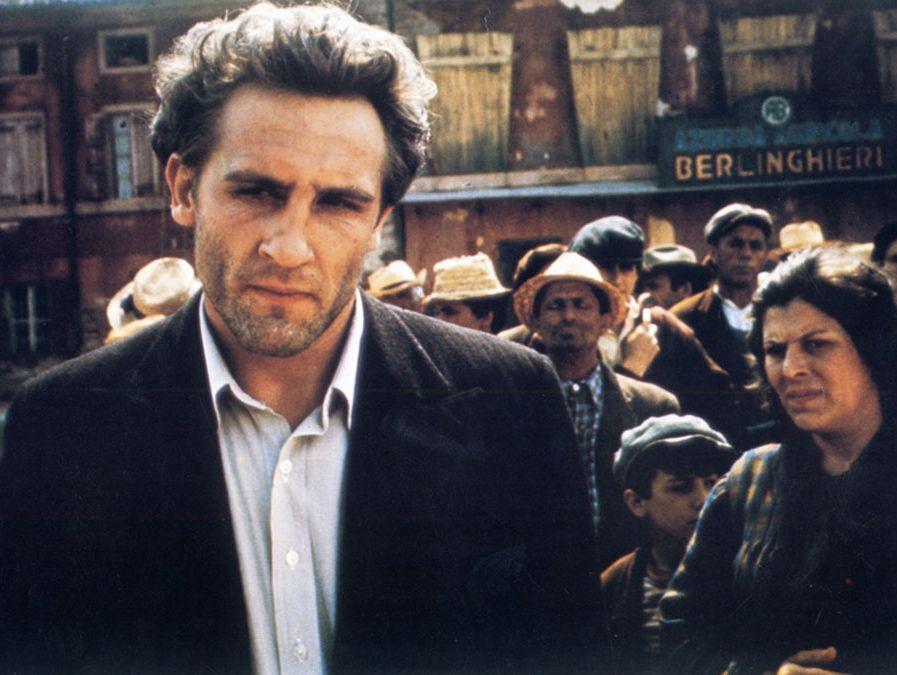

“Novecento” (also released as “1900”) is Bernardo Bertolucci’s most ambitious work, as it sets to tell the story of Italy’s biggest socio-political events through the parallel stories of two men, the wealthy landowner Alfredo Berlinghieri (Robert De Niro) and the lower-class Olmo Dalcò (Gerard Depardieu), who works for Alfredo.

The full cut is 317 minutes long, and is often shown in two separate parts. Initially, a 247-minute cut was made by Bertolucci after concern from the studio about the film’s length, and this was the version shown mainly in the U.S., while most of the other countries got the longer, two-part version.

The film has two great performances by De Niro and Depardieu, but the supportive cast is particularly impressive, especially Burt Lancaster and Sterling Hayden, playing the two protagonists’ fathers, and Donald Sutherland’s fascist farmer Attila. “Novecento” is at the same time a great, Hollywood-like epic, and also a tale of political ideals linked to personal relationships.

The film suffers from its own ambition but remains a great spectacle, with cinematography by the masterful Vittorio Storaro and great themes of love, morality, and social differences. The longest cut of the film remains the most worthy to be seen, in order to fully immerse in the 20th century world Bertolucci had recreated.

3. Fanny and Alexander

In 1976, Ingmar Bergman ran into trouble with Swedish justice after an accusation of tax evasion. After the charges were dropped, a very shaken Bergman went into exile and vowed to never work in Sweden again. The promise was broken six years later when he directed “Fanny and Alexander,” which is not his last great film, but certainly his last masterpiece.

Its length varies between different versions, since it was initially made for being broadcast on TV, and later also shown in theaters. The first theatrical cut was just over three hours, while the TV version (split into five episode, with a prologue and an epilogue) and the subsequent theatrical releases were 312 minutes long.

The film follows a partially autobiographical story of family told through the experience of the young siblings Fanny and Alexander. They find difficulty in restoring the harmony in the family after their father’s death and the new marriage of their mother to a bishop, who represents the strict religious side of Sweden Bergman had observed while growing up.

The film is a masterpiece of storytelling and a wonderful-looking film, thanks to the cinematography of the great Sven Nykvist. The story of lost familiar harmony that eventually is found again is told with the touch of a great filmmaker and manages to be one of Bergman’s most convincing works.

4. Shoah

“Shoah” by Claude Lanzmann is one of the great masterpieces in the history of documentaries. It stands as a monumental and impressive work with a length of 566 minutes and an enormous historical relevance.

The film exclusively features footage from the present, and shows the interviews of men and women who were both survivors and perpetrators during the Shoah. Lanzmann famously worked 11 years on the picture, shooting and then editing 350 hours of footage. He avoided voiceovers, making the footage as direct as possible, and even went to the trouble of shooting some former German SS with a hidden camera, a trick that actually got him attacked and hospitalized in real life.

Lanzmann is relentless in his act of filmmaking, and was determined to make a documentary that is first and foremost an act of witnessing, probably the most precise and detailed recounting of what happened in the concentration camps.

The emotional effect of seeing the former prisoners telling their stories, sometimes with great difficulty, can truly be life-changing for the viewer. Seeing nine and a half hours of such footage is an extremely demanding task, but those who go through with it can give testimony of one of the greatest achievements in documentary and filmmaking history.

5. Satantango

In 2011, renowned Hungarian director Béla Tarr announced his retirement from directing feature length films. The announcement came after the release of “The Turin Horse,” at the end of a long career during which he created a very recognizable style that made him one of the most known names of artistic and experimental cinema. Some of his main traits are long takes and reflective rhythm, through which he conveys a peculiar sense of dramatic tension and a sense of philosophical deepness.

“Satantango,” which he released in 1994, runs for seven and a half hours, and is based on the novel by his regular collaborator László Krasznahorkai. It is divided into 12 chapters, following the events surrounding an Hungarian village, with a great number of characters, all broken or desperate in some way. The chapters are not necessarily in chronological order, and most of the shots are made in extremely long takes.

This is one of Tarr’s most appreciated works, as it effectively depicts a micro-world where hope seems to have lost its way in the characters’ lives, while a dark menace loomed over them. It is a strongly pessimistic picture, and maybe the most immersive of Tarr’s filmography due to its challenging length, but for those used to Tarr and his style, he has reached few times such a level of effectiveness in his artistic intents.