Our worst subconscious demons tend to burn the most frightening of images into our memories; it’s as if we truly lived these moments. Good dreams are hard to come by again, but the bad ones never leave us alone. We wake up in a cold sweat, and we have to calm ourselves down to assure that the previous minutes of our life were not actually real.

Well, they are real to an extent, because much of life is our perception of it: what our eyes interpret, what our pain receptors indicate, what our ears convert into sound. Our brain has conjured something else, and – while it is not a part of the physical, living world – it remains a part of ourselves. The damage has been done.

Filmmaking is one of the greatest mediums when it comes to channeling these figments of imagination. Clearly, there were set images, sounds, and scenarios that these directors couldn’t shake off. If not, they have enough experience with the darkest corridors of our minds to create their own scenarios.

Some of these films actually are bad dreams, while the remaining films are the real world collapsing around the main characters in a similar fashion. Here are ten great movies that are close to being nightmares themselves.

Be cautious of spoilers ahead.

10. 3 Women

While Ingmar Bergman’s Persona decidedly broke cinema as a language, Robert Altman’s American answer, 3 Women, still wanted to use film as a vessel for his message. Most of the film circles around two women, played by Sissy Spacek and Shelley DuVall; the mysterious third woman lingers in the background, mainly, like the figures of our most wondrous dreams that we cannot put a face on.

Spacek and DuVall’s characters seem set in stone at first, until they shapeshift, and even converge and amalgamate. They split apart into new beings by the time we finish the film, and we aren’t even entirely sure which part of this journey was real (if any of it at all was). Toss in some aquatic, dreamy imagery, and the monstrous mosaics that haunt the film, and you have this lavender-clad onslaught.

9. Anomalisa

In the stop-of-motion stop-motion film Anomalisa, the entire world shares one voice and one face; everything is monotone. This isn’t a midlife crisis, but the end of a life begging to finish its course once and for all. Charlie Kaufman knows how to channel misery and existential dread. Right off the bat, everyone is a poseable figure (the cracks in everyone’s faces is not edited out, further embedding the faults of the entire world being exposed).

Finally, a breath of fresh air happens, in the form of Lisa; her voice is starkly different, and her physical being is of its very own. Michael stops everything to find a new life with this ray of light, only to discover that the world wasn’t the problem; rather, he is his own inescapable curse. The film turns meta (figure faces start to jumble, and even fall off, unveiling the mechanics underneath), and that’s when Anomalisa comes full circle as a taste of purgatory on Earth.

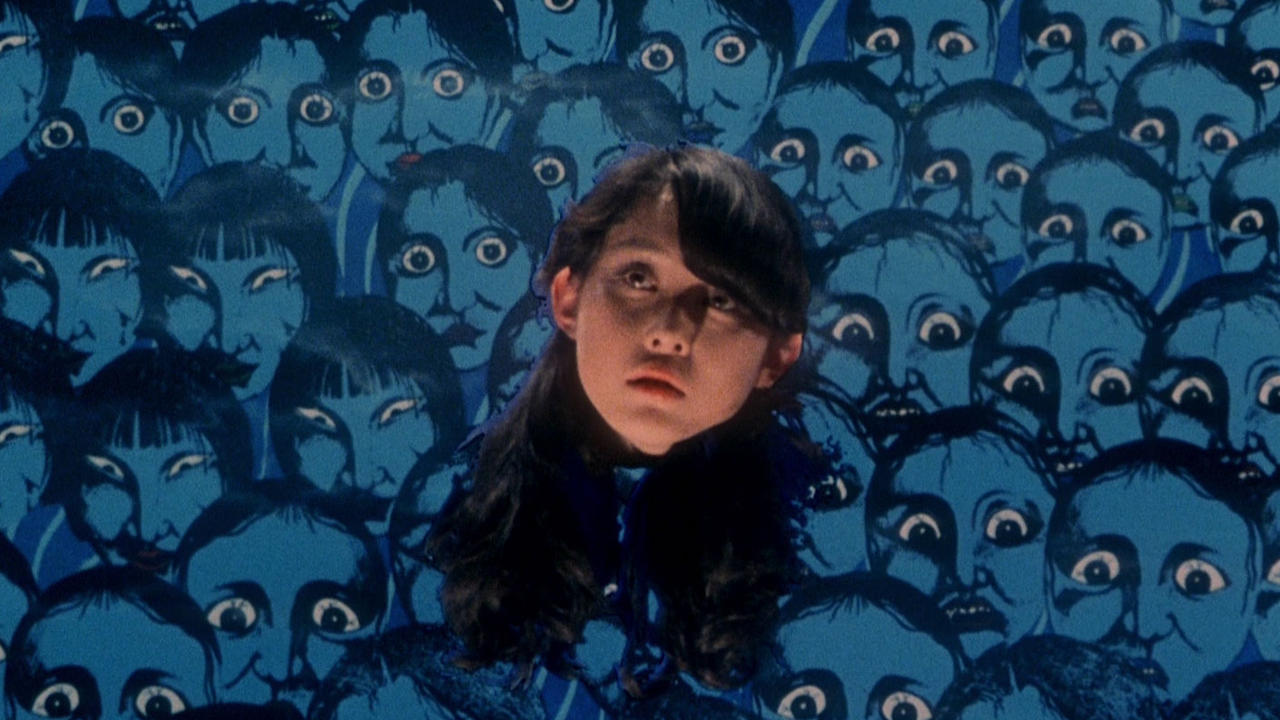

8. House

The very premise of the cult hit House is not even a nightmare that somebody had, but almost like a nightmare someone tries to come up with. It’s so extreme, that it doesn’t even seem feasible that anyone could come up with this in their sleep (not that any of these films were actual dreams that these filmmakers had, but all of them are reasonably comparable with the dreams we have). However, what makes House actually feel like the product of our hectic minds during an episode is the way these ideas are presented.

The animation and chroma key effects are so outlandishly awkward, you feel so uncomfortable witnessing them. Nobuhiko Obayashi intended for these scares to seem as though they came from the mind of a child; mission definitely accomplished. Because House feels like a nightmare that a child came up with, and not an adult, it seems to creep into your psyche just a little bit. It’s so over the top, but its idiosyncrasy makes it just a little too real.

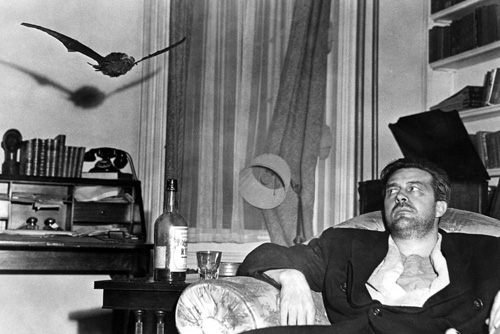

7. The Lost Weekend

Addiction is a curse that many people face. Billy Wilder’s adaptation of the Charles R. Jackson novel The Lost Weekend is a deep look at one basic premise: how addiction truly can take a hold on your life. Don is a writer on a mission, and his craving for alcohol starts to somewhat get in the way.

The film begins to flip its purpose as we reach a considerable length into the story. We no longer are concerned with the story being written, but rather his losing fight to his addition. When we reach the scariest moments of the film, where we experience Don’s withdrawal hallucinations, we suddenly have entered a world we are unfamiliar with. We’ve gone too far.

Don’s subconscious has entered his real life, and it has many things to say to him (in the form of a bat, apparently). Yes, The Lost Weekend will make you feel as though you experienced your own nightmare by the end of it.

6. Meshes of the Afternoon

Well, of course this iconic short is here. Maya Deren was an expert at conveying how dreams work on film long before most of your favourite directors were trying to achieve the same goal. A cryptic story with visual (and audible, thanks to Teiji Ito’s score over a decade later) cues leads you on. Then, it restarts and lunges forward with some slight differences. You’re never quite sure where you are, what you’re seeing, and what you’re receiving.

By the bitter end, you know you’ve witnessed something damning. Have we escaped the many layers of a dream? Was this all a dream? Of course, you will have answers after you watch the film, but your first ride through will be a complete miasma.