Sometimes the first shot turns out to be the best, as these filmmakers have proven. Not that these director’s have only made one good film – although there is one exception – however, their debut feature has remained the greatest effort of their career, for varying reasons. There are some great filmmakers on this list, while others’ may have just had that one great idea.

Nevertheless, the films on this list are notable for their lasting impression on audiences, cultural impact, or simply their ability to immerse audiences. Here are ten directors who have never surpassed their debut feature.

10. The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, US, 1955)

To say this was an obvious choice to commence this list would be an understatement. Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is arguably one of the greatest feature-film debuts of all time, and gave birth to one of the most iconic and terrifying villains in cinema history. This is no short praise, and it is very deserving, which makes it such a shame that Laughton was unable to grace audiences with another piece of work.

The English stage and film actor passed away from cancer at the age of 63 in 1962, seven years after the release of the film that would later go on to become an indisputable classic. Film fans have long debated what could have been – of a director’s career that could have been truly spectacular, and yet, for many cinephiles this solitary effort is enough, because it truly is an outstanding blend of genres, coming together to make something unique, eerie, and frankly, quite perfect.

Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) sits in a jail cell shared by a man named Ben Harper (Peter Graves), and upon Powell’s realisation that his cellmate awaiting execution has a sum of $10,000 stashed away, a determined greed is provoked . Upon release, the religious fanatic visits the deceased’s home and attempts to acquire the money, by any means necessary.

Mitchum’s performance is incredible, striking a balance of sickly charm and downright boogeyman. The speech of right hand/left hand, of good and evil, is an iconic moment in cinema history, and has been referenced and revised by many filmmakers, most famously by Spike Lee in Do the Right Thing.

It’s a magical moment in a film which has many, although the magical quality stems from the film’s dreamlike – or rather, nightmarish – quality. This is a result of the stylish cinematography, which achieves the look of a gorgeously shot gothic-horror, complimented through chiaroscuro lighting commonplace in the film noir genre, of which The Night of the Hunter shares elements with.

It is an unforgettable experience, and that was the aim all along. Upon her casting, Laughton said to Lillian Gish (who plays the role of Rachel Cooper): “When I first went to the movies, they sat in their seats straight and leaned forward. Now they slump down, with their heads back, and eat candy and popcorn. I want them to sit up straight again.” For over six decades now, audiences have been sat upright in fascination when watching the directorial-debut of one of cinema’s most auspicious filmmakers.

9. Gummo (Harmony Korine, US, 1997)

The California-born filmmaker has definitely made a handful of great films; Spring Breakers being the obvious example to come to mind, however it’s hard to consider any of his output outshining his fascinating directorial debut.

After writing the script for Larry Clark’s debut – Kids – at the age of nineteen, Harmony Korine quickly turned to making his own feature and the results were remarkable, and yet, the film sadly alienated many critics.

Mark Caro of the Chicago Tribune slated the film, saying that “There’s a difference between unblinkingly observing reality and wallowing in degeneracy.” This seems like an unfair reading, failing to account for just how dangerous the film feels to immerse yourself in, and that may just be the point – the world presented here is inescapable, suggesting that the viewer’s right to disengage and leave isn’t a right held by the inhabitants it portrays.

The film is a portrait of small-town America torn apart by a tornado, causing a devastation urging many to leave, apart from those that cannot. The audience follows the lives of numerous characters, offering a glimpse into the shattered spirits of numerous residents.

The characters are certainly problematic, but by taking a realist approach, Korine never aims to glorify their activity, but document it and ask audiences to form an opinion. He wished for their behaviour to feel real, which is why he approached people in casual locations, requesting them to be in the film and therefore giving the film an authentic texture.

Gummo almost feels like a documentary made by the natural disaster itself; a spectral observation looking upon the damage it has caused in surprise that poverty-stricken lives remain. It has gone on to achieve prominent cult-status, and it’s no surprise.

It is disturbing in places, packed with unique imagery, and is certainly original in every aesthetic consideration. Disagreeing with many, Korine is a brilliant and intriguing filmmaker, and although his ideas have continued to hold an interest for cult audiences, it all started here, and it’s a world we are often pulled back to.

8. Amores Perros (Alejandro G. Inarritu, Mexico, 2000)

Perhaps the most surprising entry on this list is critically-acclaimed Mexican filmmaker Alejandro G. Inarritu, director of The Revenant and the academy-award winning Birdman. This is undoubtedly a very talented director who has consistently proven himself as his career has expanded, attracting wider audiences with every new piece of work. Yet, when hard pressed, his greatest achievement remains Amores Perros, or as translated, Love’s a Bitch.

Inarritu interweaves three tales which are connected through a hideous car crash. The audience is introduced to the violent world of illegal dog-fighting, the struggles of a model confined to a wheelchair, and a mysterious hitman. The stories are also linked by the presence of dogs, and the ways in which these animals can personify and represent their owners and their situations.

The depiction of animal violence is so viscerally portrayed that the film only just avoided being banned in the UK by the BBFC, who were eventually persuaded to release the film uncut after being assured that the fight-scenes were meticulously simulated. The film was controversial for these scenes, however, critics, fellow filmmakers, and audiences alike praised the film as one of the greatest pieces of world cinema in years.

The film is exhilarating for it’s entire two-and-a-half-hour duration, and the fact that a debut-feature showed this amount of skill and confidence is jaw-dropping. It manages to be many things: gritty, heartfelt, observational, and above all, so overwhelmingly exciting.

This is the work of a great filmmaker who aspired to the likes of the applauded Quentin Tarantino, and by approaching a project in the structural style of Pulp Fiction, made something that was able to resonate with American audiences and still depict the culture of Mexico City in unconceded fashion.

Amores Perros is a study of cruelty, loyalty, violence, and humanity, and although the filmmaker would go on to great success, more so than perhaps anyone else featured on this list, his first effort remains his most compelling, and when looking at his body of work, his status has come as no surprise.

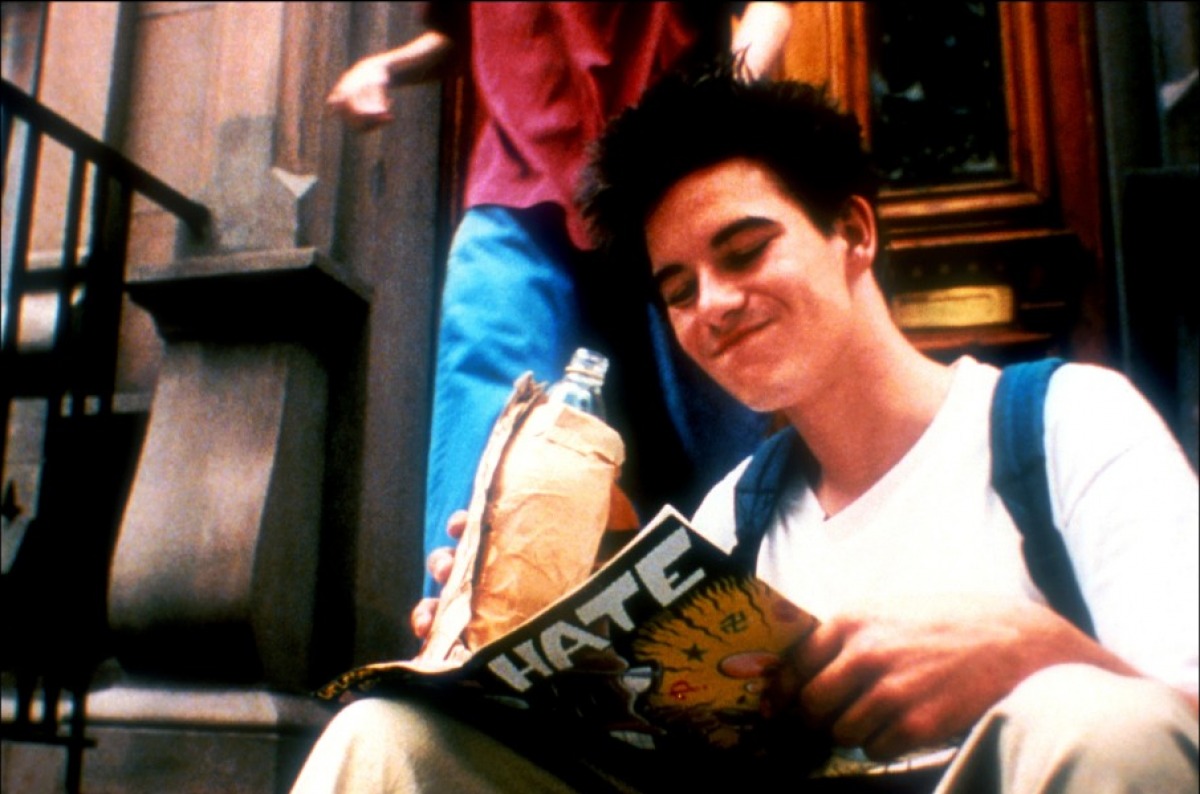

7. Kids (Larry Clark, US, 1995)

It is fair to say that audiences’ disapproval of the controversial treatment of teenage life undermined the importance of Clark’s frightening statement. Released during the height of the New Queer Cinema which began to fearlessly and creatively address AIDS paranoia, Clark decided to take a realist and stripped back approach to this universal fear and present audiences with a group of kids whose behaviour will unknowingly lead to the destruction of many lives.

The popular claim that Clark glorifies the teenage sex he depicts is ludicrous. The exposition displays two teenagers negotiating intercourse; their bodies are made to appear sweaty and gangly, with protagonist Telly’s conniving and hollow words falsely suggesting respect for the young girl in front of him, immediately intending to unsettle the audience. Sex is represented as a danger, but it’s acknowledged that it is an imperative urge of all teenagers, and Clark cleverly crafts a horror film in which the antagonist is the teenagers own desires and naivety.

“Virgins, I love em’, no diseases…” announces Telly’s – our protagonist – inner monologue. He and his friend Casper are very much alike, and the narrative follows them over the course of a day, disrespectfully chatting about girls, drinking, skateboarding, and basically getting up to no good.

Korine’s script is insightful and feels well researched, part in fact because he associated with the crowds his screenplay depicts, and along with some improvisation from the actors, the film possesses a sense of frightening authenticity, making issues of sexual danger appear all the more real.

Roger Ebert famously defended the film, saying that “Kids is the kind of movie that needs to be talked about afterwards.” The direction appears minimal, with everything the film shows merely appearing to be placed in front of the camera, and this is to enforce Clark’s agenda that what we are witnessing is a real life issue – of teenagers who are only interested by deviance.

One way to view the film is as a revision of the famous scene in Disney’s Pinocchio, of young boys engaging in behaviour that distorts their very form. However, Clark is addressing that in the real world, the repercussions of such actions are much more severe, and concluding this nightmarish day-in-the-life tale with the words “Jesus Christ, what happened?” offers a bold and final statement, directly addressing the audience in wondering how adolescence has reached this point. The filmmaker has gone on to consider teenage hell throughout his career, but never to such thought-provoking effect as this.

6. Nails (Andrey Iskanov, Russia, 2003)

Certainly the most obscure name on this list, Andrey Iskanov is an underground Russian filmmaker that some of the more specialist genre fans will recognise. Perhaps better known for Visions of Suffering and Philosophy of a Knife, his debut-film remains his most accomplished, interesting, and appropriately experimental work.

Gvozdi (Nails) tells the story of a hitman in Eastern Siberia whose mental health has gradually been effected by the violent nature of his career. Suffering a bizarre turn, he retires to his apartment building and decides to hammer nails into his head, causing a series of hallucinations and paranoid delusions. His actions are that of a man who is desperate to gain a new experience and witness something beyond his soulless existence, yet what he witnesses is a realm of insanity which promises no solace – quite liking watching this film, really.

It’s a very experimental and avant garde production, and frankly there isn’t anything else quite like it. It was made on such a low-budget, which when translated into US dollars estimates at a low $160, of which results in some rather amateurish elements. However, on the whole, Iskanov manages to craft something singular and enticing; an art-house splatter film of nihilistic intent, made up of visually distinctive sequences.

It’s atmospheric, and pushing in at a mere sixty-minutes, is sure not to overstay it’s welcome, as Iskanov was surely aware that the film he made could be interpreted as somewhat of a “bad trip”, one that audiences won’t wish to inhabit for longer than necessary.

The director’s feature-efforts after Nails continued to exhibit a similar aesthetic style, and certainly have their appeal. However, while Nails isn’t a great film, it is a new and memorable experience for those who sometimes find themselves venturing into more unknown cinematic territories. If you identify with this activity, then Gvozdi is a rare-gem worth seeking out.