6. A Clockwork Orange (1971) – dir. Stanley Kubrick

Curiously, Stanley Kubrick’s distressing exploration of the “old ultra-violence” was banned in Great Britain at the director’s own request, following threats and protests aimed at him and his family. Kubrick’s ambition to explore the psyche of a wrongdoer, sometimes to the detriment of the victims who are either deprived of their individuality or coarsely caricaturized, led to a series of crimes allegedly inspired by this plunge into human baseness.

The philosophical scope of the narrative of “A Clockwork Orange” as well as Kubrick’s critique of behavioral psychology were clouded by the deliberately provocative nature of the images, which resembled more those of an exploitation film than those of a substantial political allegory.

With the benefit of hindsight, contemporary spectators can extirpate themselves from the web of controversies which the film got entangled in at the time of its release. What remains today is Kubrick’s commendable capacity of synthesis, which is visible in all his adaptations (the majority of his body of work is made of more or less straight-forward adaptations) and his ability to create striking visual compositions that easily made the transition to cinematic myths.

However, the film-maker’s affirmation concerning the protagonist Alex DeLarge’s symbolism (who is supposed to embody man in his natural state) is highly debatable; but maybe the fact that this dispute still rages on is the ultimate proof of the relevance of “A Clockwork Orange”, then and now.

7. Life of Brian (1979) – dir. Terry Jones

Humor has always been the most efficient means of persuasion and pamphlet has often proved to be the most striking political manifesto because they speak directly to the affects and they do not exude condescendence or didacticism, as many other channels for conveying ideas do.

The Monty Pythons’ “Life of Brian” is infused with essentially Christian values, as it fondly celebrates the protagonist’s naïve generosity and it promotes a dignified resignation in the face of both the vicissitudes of life and death. But it is the coating of these themes with burst of absurdist humor, innumerable references to popular culture and a total irreverence for the religious imagery and mythology that caused outrage amongst the faithful, the Christian community demanding and obtaining that the film be banned.

As in the case of Stanley Kubrick’s “Clockwork Orange”, whose violence led some to believe that the film was an incensement of its character’s innate immorality, viewers are often lured by the purposefully provoking reading of the life of Christ and tend to ignore how “Life of Brian” sheds in fact a positive light on the core principles of Christianity.

The Christ is sometimes jokingly called “the first socialist”, and the Monty Pythons’ film tries to unearth the foundation of his teachings, namely tolerance and brotherhood between humans, while harshly criticizing the pitfalls of organized religion and of its spawn, obscurantism.

8. Cruising (1980) – dir. William Friedkin

The controversy surrounding William Friedkin’s “Cruising” has changed object over time, and this gradual shift is a very telling mirror lifted to the face of our society. To the bemusement of many incurable pessimists that exclusively focus on the downsides of modernity, the image this mirror reflects is – for once – a flattering one.

Initially, “Cruising” was censored and later heavily re-edited due to the perceived crudity of its depiction of the homosexual sadomasochistic milieu. It is not absurd to assume that the brutality of the police forces – that display the most crass disrespect for the presumption of innocence – , their blatant homophobia and their total insensibility (directed even towards their own, as the way the protagonist’s doubts are carelessly brushed aside by his superior proves) also played a role in the decision to ban the film.

With time, the frequent depiction of sexual acts on cinema screens raised the audience’s tolerance; simultaneously, the homosexual community became more visible and more vocal, especially in the wake of the HIV epidemic.

Western societies slowly started to become more inclusive and even today, the process is all but completed. But it is well-engaged and probably irreversible, and as a result a contemporary spectator is likely to be consternated by the fact that Friedkin’s “Cruising” is buttressed by a myriad of clichés, one staler than the next, concerning the world it endeavors to paint.

9. Je Vous Salue, Marie (1985) – dir. Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard’s name is customarily associated with political cinema, albeit more with its avant-garde branch that sought to redefine cinema alongside society. His style, however, which can be roughly defined as a combination of Brechtian alienation techniques with a sort of dislocation of classical narration through means that are specifically cinematic (like intertitles, infinite variations on the mismatch between sound and image, disrupting cuts, etc…), seems inherently suited to more ineffable subjects.

Therefore, his retelling of the Immaculate Conception in “Je vous salue, Marie”, followed years later by “Hélas pour moi” (1993), reach a synergy between form and content that make these two films the most fluid and the most serene of Jean-Luc Godard’s career.

Despite the formidable stir it created in the midst of the Christian community – commotion which led to the banning of the film in a number of South-American countries and to its public denunciation by Pope John Paul II, “Je vous salue, Marie” is a luminous meditation on the feminine condition, which features perhaps what is the most aesthetic and de-sexualizing handling of the human body in cinema. Even its typically Godardian interruptions feel like integrated parts of a rippleless whole.

In spite of the fact that many critics decried the perceived solemnity of the film, humor sometimes surfaces (mainly in the characterization of the angel Gabriel, who is a foul-talking thug), while never turning into derision.

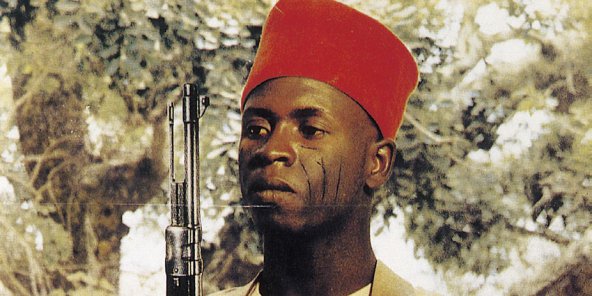

10. Camp de Thiaroye (1988) – dir. Ousmane Sembene

It is not difficult to understand why Ousmane Semnbene’s historical fiction about the Thiaroye massacre was banned for ten years in France. Not only does the film meticulously revisit all the circumstances that led to the carnage committed by the French army, clearly and fiercely assigning blame, but it is also a vibrant manifesto against all form of occupation of a territory by whoever doesn’t inherently belong here.

The power of the film lays in the fact that it relies more on visuals than on narrative to express this particular message: white people do not own Africa, not because ethics and justice prevent it but because Africa organically rejects them.

And indeed, all white characters seem out of place, dominated by the immense open spaces, their skin an unhealthy color, their emblems of power pompous and nonsensical, their language appropriated by the Africans and thrown back at their faces without them understanding a single word of this new dialect.

The natives, on the other hand, move freely and gracefully and the director and the cinematographer Smaïl Lakhdar-Hamina marvelously incorporate their skin tones in the general color scheme, creating compositions of striking beauty.

“Camp de Thiaroye” feels like a Senegalese version of “Battleship Potemkin” in its depiction of the slow ascent of tension (which is initially caused by the nauseating food the soldiers are served, just like in Eisenstein’s film) and its tragic denouement. Tragic, but infused with hope, as victors and vanquished would soon trade places.