5. La Notte – The letter

The yearning for love to escape from the ravages of time is the theme of the letter that Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) reads to Giovanni Pontano (Marcello Mastroianni) at the end of “La Notte.” Lidia decides to read the letter to Pontano after a day in which we have seen the decadent nature of not only their relationship, but also the entire world that surrounds them.

In the film, we witness the sunset of two lovers and all the figures and characters of their world. Everyone is tired of performing their role; the time has exhausted a world that just gets worse and worse. To be lovers is just another role that has been degraded by time and appears to have lost its meaning.

Have seeing all of this decadence, Pontano tries to hold Lidia one last time. Both of them know that they do not sincerely love each other anymore, so Lidia read him a letter. In the letter, a man speaks to Lidia; he sees her with absolute infatuation and wishes that the night (in Italian, la notte) in which he writes never ends, that time never corrupts their love.

The man who wrote this is Giovanni Pontano, but he does not remember it. They see each other, and we see them, knowing that nothing can escape time, that time which corrupts and exhausts even the most noble ideals. And as Pontano tries to desperately kiss Lidia, we feel his despair.

4. Les 400 Coups – The run

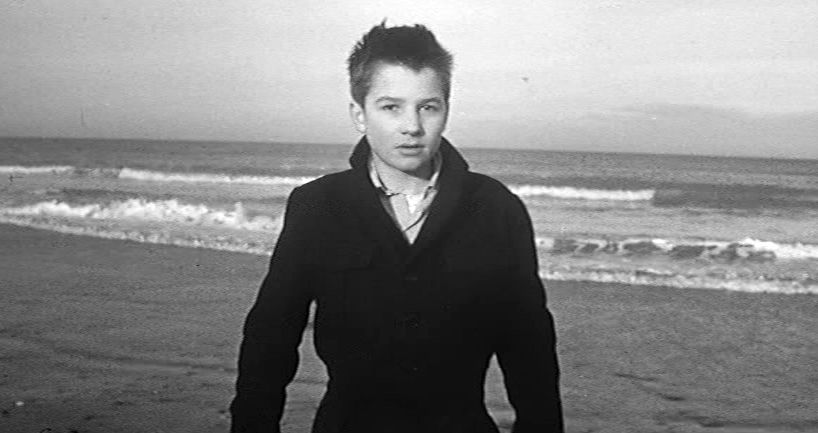

What has not been said of Francois Truffaut’s iconic masterpiece? In the last scene of the coming-of-age film, Antoine Doinel’s (Jean Pierre Leaud) childhood is over. Through the film, Antoine discovers explores freedom and rebellion. He lies, he disobeys and he escapes. He is punished and sent to a reformatory for his behavior.

While the boys in the reformatory play soccer, he again rebels in search of liberty and escapes the reformatory. He runs, followed by a guard, but he manages to lose him. Antoine keeps running and running. He is in a constant escape.

But when he arrives at the beach and stands near the ocean, letting the waves touch him, he stops. He stands in the ocean and looks at the camera. He looks confused, as if he doesn’t know what to do or where to go. He feels as we all felt at his age, and the shot freezes in that moment of doubt when childhood is irremediably over.

3. Late Spring – The father arriving home

“Late Spring” is the story of a father and daughter who love each other. The father (Chishu Ryu) is worried that his almost 30-year-old daughter (Setsuko Hara) will be left alone when he dies, so he wants to marry her off, even though it will mean her leaving the house which they lovingly share. Noriko (the daughter) does not want to leave her father alone, and refuses to consider marriage.

Through the film we see Setsuko being pressured to find and accept a husband so she doesn’t end up alone for the rest of her life. She constantly refuses to even consider it as he continuously comes back to the house of her father. We see their relationship with the sober and minimalistic style of Yasujirō Ozu, who manages to immerse us in the rhythm and atmosphere of the life in a house that has its days counted.

Eventually, the father and the daughter have a face-to-face talk about the marriage of Noriko. Even though he loves the company of his daughter, he desires what is best for her, not for him. Thus the father talks to Noriko about the need to leave one’s home to build a new one. Noriko listens and gets married. We do not see the wedding; we just see the old man getting back home.

Now he is the only inhabitant of the house; the father is alone. The musical theme plays as he peels an apple. The idiosyncratic Japanese smile is not on his face anymore. With a single gesture he suggests is anemic, Ryu slightly lets his head drop and stops peering at the apple. We see and old man who misses his daughter but will never say it in order to keep her from worrying about him.

2. City Lights – The smile of Charlie

The ending of “City Lights” is one of many encounters between a tramp (Charlie Chaplin) and a blind girl (Virginia Cherrill), but this time she is no longer a blind girl. The scene starts as expected with Charlie embarrassing himself after a chain of misfortunes in which he was trying to help people.

And then they see each other. He immediately recognizes her and even though she doesn’t recognize him, she is still kind with him. She goes out of a store in order to give him a flower, and he tries to escape maybe because he know their love is not meant to be, but she reaches him and their hands touch.

As their hands touch she recognizes something, and we, along with Charlie, understand that she remembers him by the kind touch of his hands. In that moment, both of them and us along with them remember what they have been through.

Charlie struggled to help her; we have seen his struggle, and the sacrifices he has made freely for her. The only reward he needs is seeing her happy; she knows this and looks at him with both sadness and gratitude. Their hand are touching and Charlie smiles, leaving us with the ambivalent musical theme of “City Lights,” touched by the unconditional love of a tramp for a blind girl.

1. Cinema Paradiso – Nuovo Cinema Paradiso

The ending of “Cinema Paradiso” could not be left off this list; just as the scene in Ulysses’ Gaze, this moment has a lot to do with the memory a lost past. It is the conclusion of Toto’s story with Cinema Paradiso, thus with his hometown and his first love.

It is a very simple scene, consisting of Toto (Jacques Perrin) seeing the surprise that old projectionist Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) crafted for him. It is a movie made of all the fragments that Alfredo had to cut due to their romantic and sexual content. Toto worked for Alfredo in exchange for these fragments, but he never gave them to him. Now as a postmortem gift, Alfredo finally gives Toto the fragments of these films.

The power of this scene lies in everything that is behind it. We have seen the childhood of Toto, the early love for cinema, for a woman and for his town, and how these passions forced Toto to decide. How he lost something and gained others. But most importantly, we remember the early and innocent passion of Toto. This innocence is lost for Toto and for every human being who grows up. The ambivalent feeling we get when watching this scene is because it is a reminder of that which we lost but we never forget. And as Mexican poet José Emilio Pacheco said, “Everything that you have lost, they concluded, is yours.”