“Annie Hall contains more intellectual wit and cultural references than any other movie ever to win the Oscar for best picture… no wonder it’s just about everyone’s favorite Woody Allen movie.”

– Roger Ebert

La-di-da, la-di-da, la la

A commercial and critical hit, and winning four of the five Academy Awards it was nominated for––including Best Picture of 1978––Annie Hall was also Woody Allen’s coming of age picture.

Prior to Annie Hall, Allen’s cinematic achievements embraced pure comedies, like the Marx Brothers-influenced slapstick high jinks of Bananas (1971), Sleeper (1973), and Love and Death (1975). While these films performed well and were incredibly funny, they lacked the emotional and edifying importance and outright cinematic audacity of Annie Hall.

A contemporary screwball comedy, one that would devise the template that all modern rom-coms would follow, Annie Hall was and remains a bittersweet merry-go-round tinged with affection, indecision, tendency, and adoring pop psychology.

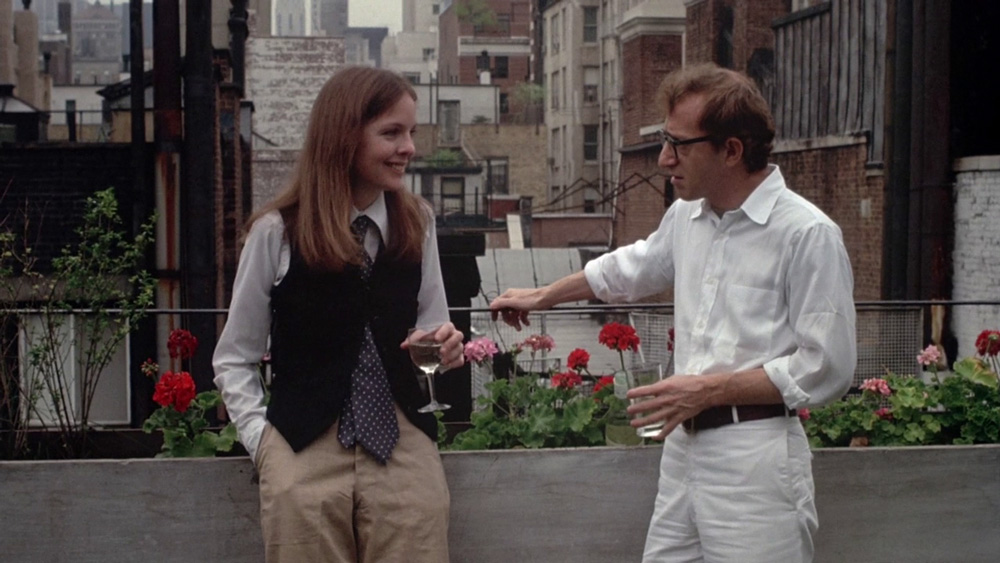

Centralizing on the to and fro romance between Alvy Singer (Allen), a neurotic, libidinous comedian and the ever-amicable Annie Hall (Diane Keaton), would starry-eyed, relationship-centered cinema and au courant pillow talk ever be the same again?

“Love is too weak a word for what I feel –– I luuurve you, you know? I loave you, I luff you, with two F’s.”

– Alvy Singer (played by Woody Allen)

When you were mine

Bookended by a pair of stock Borscht Belt jokes––one about a Catskills Mountain hotel with terrible food, the other about a confused sibling who thinks he’s a chicken––Allen’s career as a performer launched via stand-up comedy, so this framing device is something of a security blanket perhaps, but it also allows for Alvy to speak directly to camera, establishing the often surreal, self-referential and at times almost experimenta; meta techniques that the film frequently falls back on.

At regular intervals Alvy, and Allen by proxy, knock down the fourth wall, addressing the audience with alacrity, for laughs or just as importantly, for a little cry. In Stig Björkman’s book “Woody Allen on Woody Allen”, Allen explains his reasoning, “I felt many of the people in the audience had the same feelings and the same problems. I wanted to talk to them directly and confront them.”

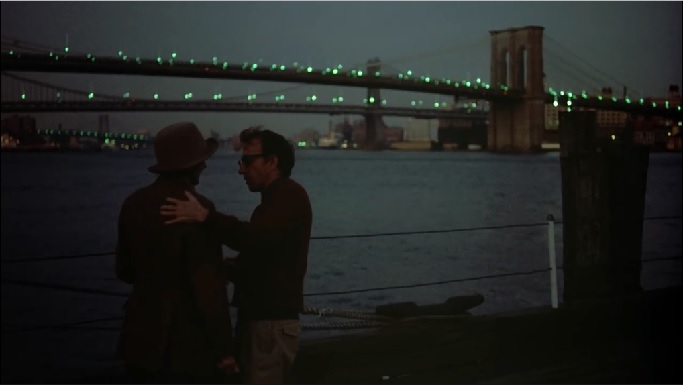

Braided and bound with stand-up comic bits, postmodern genuflections, sharp remarks about love, relationships, and sex, not to mention the discrepancies between Los Angeles and New York City, Annie Hall is first and foremost the story of Alvy and Annie’s affair. We meet the couple immediately after they’ve broken up for the last time and their nostalgia-addled stroll down memory lane is lamentable, but also affectionate, droll, and delightful.

“The question at the heart of the film is: what went wrong? How did the romance die? Alvy introduces his story as an autopsy, a re-examination of his life and behaviour, and a doomed attempt to find out why his relationship with Annie failed. There is no answer: just a deeply touching, funny, brilliantly told story.”

– Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian

I am trying to break your heart

Disputably Allen’s most sincere movie, Annie Hall is also his most emotionally sophisticated––even with emotional imperfection being a dominant theme.

Allen has always insisted that Alvy is a non-autobiographical character, but as far as a self-portrait––Alvy, like Allen, began his career writing gags for established comics, for instance––it’s undeniably him. Considering that Keaton, who briefly dated Allen, was born Diane Hall and all her friends used to call her “Annie” suggests a more confessional nature, as well.

“I’m not haunted by Annie Hall. I’m happy to be Annie Hall. If somebody wants to see me that way, it’s fine by me.”

– Diane Keaton

With the release of Annie Hall, Keaton found herself something of a fashion icon all of a sudden. With her men’s attire; hat, tie, vest, and slacks (much or her own wardrobe was used in the film), Keaton’s quirky, self-effacing portrayal of Annie was, in the bat of a lash, rakish, and all the rage. In the wake of the film, especially in North America, pantsuits, and men’s clothing became sought after attire for women.

Annie may be at times incoherent, her tennis backhand may be a little lunatic, and her driving skills a tad terrifying, but she’s also an intelligent, literate, and complex woman.

“By the end, it leaves you very hopeful about love. In this particular relationship between these two particular people, it somehow manages to have them broken up by the end of it and yet leave you hopeful about love. Maybe that’s as perfect as it can get in real life.”

– Rian Johnson, director (2005’s Brick, 2017’s The Last Jedi) on Annie Hall

Love will tear us apart

One of the many reasons that Annie Hall is a favorite amongst Allen fans is certainly owing to how self-referential the film is. It’s a film permeated with Allen’s in-jokes, opinions, and archives: his love of cinema (Ingmar Bergman, Marcel Carné, and Federico Fellini are amongst those explicitly referenced), his aversion for Los Angeles (“I don’t want to move to a city where the only cultural advantage is being able to make a right turn on a red light.”), his hostility towards television (“In Beverly Hills, they don’t throw their garbage away––they turn it into television shows.”), his obsession with death, with passivity, with the cult of personality (“Look, there’s God coming out of the mens room!”), with sex (“That sex was the most fun I’ve ever had without laughing.”), his sneering at intellectual elitism (“What I wouldn’t give for a large sock with horse manure in it!”), his zeal for Groucho Marx, and so much more.

Incipiently Annie Hall was to be even more self-engaged and solipsistic than the adored, and oft-quoted version we know and love. Originally titled “Anhedonia”––the inability to feel pleasure––it very nearly was closer to Allen’s familiar and more far-fetched comedies, with a wealth of fantasy sequences, a Felliniesque leaning, and a plot driven by a murder mystery angle.

As the story goes, much of this original conception was kiboshed by Allen’s editor, Ralph Rosenblum, who started taking his dramatic cues from Keaton’s engaging performance. Much to Allen’s credit, he wisely went with Rosenblum on this about face––and aspects of this early storyline and the reteaming of Allen and Keaton would resurface years later in 1993’s entertaining and very satisfying Manhattan Murder Mystery.

“I forgot my mantra.”

– Party guest (played by Jeff Goldblum)

Another of Annie Hall’s many pleasures is spotting all the uncommon cameo appearances and notable early acting performances from a remarkable repertoire. For instance, there’s a scene where Alvy and Annie are observing and commenting on passersby while out in public. Alvy cracks wise, “Oh, there’s the winner of the Truman Capote lookalike contest.” The ambler really IS Truman Capote––who appeared without a credit, charmed by the joke.

Perhaps even more strangely than Capote, philosopher and public intellectual Marshall McLuhan also appears in a memorable sequence, as himself––a reluctant last minute replacement for Fellini, apparently.

Minor roles and bit parts from Beverly D’Angelo, Colleen Dewhurst, John Glover, Jeff Goldblum, Carol Kane, Paul Simon, and Sigourney Weaver also flicker throughout the film.

Pictures of you

In his review of Annie Hall for Variety, film critic Joseph McBride extols the collaborations between Allen and Keaton, suggesting the pair “strike a chord of believability that makes them nearly the only contemporary equivalent of the Tracy-Hepburn films.” The classical screwball arrangement is certainly an ingredient in Annie Hall’s sensation, but it’s more than that and more, too, than the never-the-twain-shall-meet sentiments or the post-mortem of their love affair.

Annie Hall hurdles with Allen and Keaton’s natural flow, moving from one metaphysical meditation to the next, with tremendous visual ingenuity, and resolution. It’s a film running over with playful drollery, bon mots, and broken hearts. A liberating artistic step forward for Allen, Annie Hall is his chef d’oeuvre of both pathos and playfulness, an it’s also an American classic.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.