Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar Wai has been making films now for almost 30 years, and yet somehow he remains more obscure to contemporary audiences than he was about 15 years ago, when his turn of the century film In the Mood For Love won most international film awards it was presented with.

Since then, he has labored over various projects and given us a reason to forget some of his most profound work. But with this year’s Oscar for Best Picture landing in the lap of Barry Jenkin’s Moonlight, a film deeply indebted to Wong’s oeuvre, the time has come to look back and consider his whole career, ten features, up to this point.

Wong Kar Wai is one of the greatest working directors, whose cinema is rife with explorations of human connection and disconnection, sexuality and love. He comes out of an explosive time period for Hong Kong cinema in which several filmmakers rose to great acclaim (e.g. John Woo, Chow-Yun Fat, etal.).

He is often most recognizable due to his impressionistic color palette that can sometimes feel like vivid watercolors, and his collaborators, such as Faye Wong, Christopher Doyle, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, who work with him from film to film and help cement his personal style.

When ranking these films, I asked myself one basic question: how much does this film show us the world as Wong sees it? This is not merely a question of how these films look, though that is an important feature. It’s how they sound, how they see, how they constitute their little corner of Hong Kong, Memphis, or some fantasy destination where dreams come true.

Wong Kar Wai shows us how people feel in relation to each other, whether it is sexual, avoidant, emotional, romantic, in ways that those people can’t express for themselves. We see their internal worlds radiating out in the way we watch them navigate their disconnected homes and crowded public spaces.

Let’s take a look at the greatest Wong Kar Wai films, and some of the greatest films of the last 30 years.

10. My Blueberry Nights (2008)

When talking about ranking Wong Kar Wai films, it becomes easy to imagine one or more of them as the “worst” films he made. While this may technically be true, by the nature of list-ranking, it is also true that this worst film is better than many directors’ best. My Blueberry Nights transposes many of the themes that drive his earlier/better work to an American landscape.

Otis Redding crooning ballads through the jukebox, the infinite frontier offered by Nevada’s casinos, the deep loneliness of cities and the possibility at all times of flight – these are distinctly American variations on Wong’s trademarks. That places My Blueberry Nights in a tradition of films made about America by outsiders, such as Chinatown and Paris, Texas.

In an invisible diner, tucked away in the back corners of some nondescript Manhattan neighborhood – as elsewhere, the feel is more important than the facts – Norah Jones’ Elizabeth and Jude Law’s Jeremy share an intimate, vulnerable, late night conversation about love and heartbreak. He collects stories, and the people that go with them, and she needs a confessor – so they make a perfect pair.

Immediately afterwards, Elizabeth begins a journey across American highways, first to Memphis, where she ends up a bartender, then to a casino in Nevada. She connects with people, but always fundamentally in search for herself.

9. Ashes of Time (1994/2008)

From his body of work, it’s clear that the themes of desire and the sensuality of violence are deeply intertwined for Wong, but somehow he has always struggled with fully realizing aspects of that vision.

Ashes of Time is his first attempt at a traditional wuxia film, but submerged in an almost pessimistic, dystopian view. The film explores the underbelly of desire, and the things that twist up inside of people who defer or deny that desire. It’s about the torment of love, something Wong returns to again and again.

But at the same time, the film can’t quite find its way to cohesion. It’s almost as if Wong Kar Wai is seeking to show us a thing that is bigger and deeper than he is yet able to fully lay out.

Wong returned to the film in 2008 to recut it for a Redux edition, but even there it feels like you can just glimpse some of his vision without sustaining it. He is exploring the relationship between pain and pleasure, as it forms along human sexuality, and how those machinations become historic and immanent. He returns to this style with much more grace and clarity, 20 years later, with The Grandmaster.

8. As Tears Go By (1988)

As Tears Go By was Wong Kar Wai’s smash debut, rising out of the invention and wizardry of Hong Kong’s vibrant film scene in the 80s. His contemporaries, with whom he frequently collaborated before striking out on his own, included the likes of John Woo and Tsui Hark, and those influences are unmistakable here. Tears is essentially an action film, but shot thru with the sensual physicality for which Wong’s films have become famous.

The plot revolves around a seedy mob environment – our main character is an enforcer, and lives in a world similar to denizens of Scorsese films, a mixture of violence, crime, poverty and existential discontent. But here, the outlet for much of that anguish is through the possibility of connection with other people. It’s almost as if the violence comes from a place of sexual frustration, but it may just as easily work the other way around.

So many of Wong’s most recognizable images from later films have their origin here, from tracking shots in the rain to stuttering sequences cloaked in neon. These lonely cohabitants navigate their cityscape in search of each other or themselves, and find neither, except in those blissful shots in alleyways with the perfect pop song to soundtrack it.

7. 2046 (2004)

In spite of the fact that it is connected to the stories of two other films (Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love – to which it is a virtual sequel), 2046 remains an anomaly in Wong’s body of work.

As a result, it has produced a growing base of deep appreciation, many of whom prefer it to the other films listed below. It has disjointed narratives, told non-linearly, and follows multiple romances involving some of the same characters, like in Chungking Express and Fallen Angels, but it sets itself apart through its use of science fiction, and a strong sense of dream-like unreality.

Wong’s films often feel like dreams, drifting through unfamiliar worlds of brief recognition, but this is that approach at its highest peak. The film picks up the tale of the lovers from his prior film, In the Mood for Love, but transports them through and out of time so that they can make lost memories and desires manifest. This is a sacred dream space, like a hidden apartment, where the outside world and its demands don’t interfere with love.

Unfortunately, the world is not really the thing that does damage to or impedes the possibilities of romance – instead this film, along with others from Wong’s body of work, suggests that love does its own damage, invoking an idealized vision of a romantic partner that comes face to face with reality.

The real world must inevitably return – love cannot survive in fantasy. But here, in this magical space, brief moments of interconnectedness are possible, however brief, so that we can escape, sometimes, from ourselves.

6. Days of Being Wild (1991)

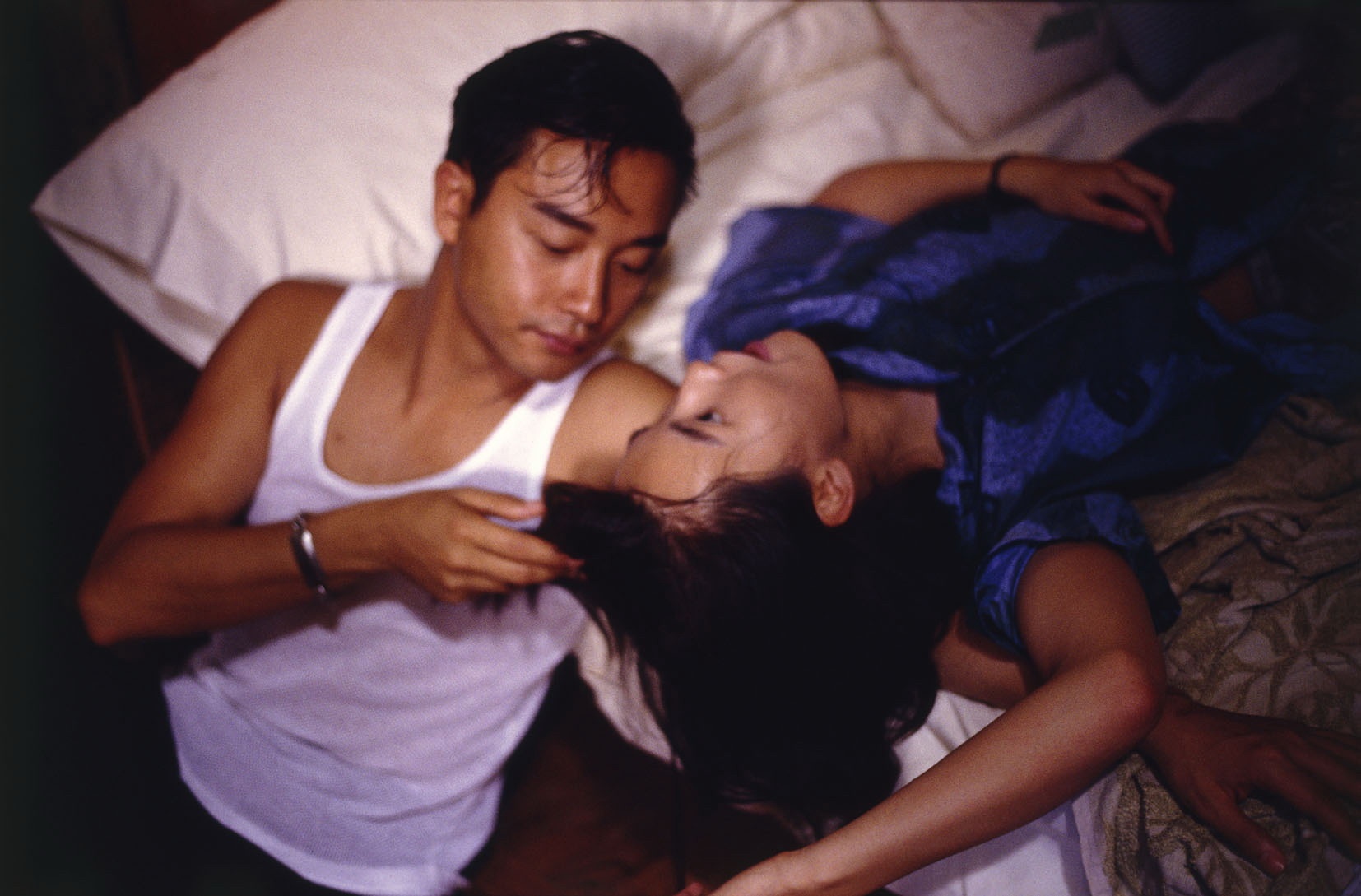

While As Tears Go By is his first film, Days of Being Wild is the first time the real Wong Kar Wai stood up. It’s the first time he would work with Christopher Doyle – his cinematographer on all of the rest of his films through 2046.

The narrative runs much closer to other lovelorn stories that populate Wong’s creative universe: disjointed moments of connection are brought together through seemingly unimportant coincidence. The thread does follow a Casanova type as he moves from lover to lover, but its more about seeking love, failing to find it, being rocked and ruled by your emotions, and the patterns we follow to nurse ourselves back to stasis.

The film is also much more specifically erotic, taking the hints from his first film and transforming them into something textured and tactile, a desire molded from sweat, steam, longing. The actors exude their characters, oozing out almost to hang suspended on-screen, caught between moments of wanting and having, between illusion/performance and the return of the real.

Those moments of profound uncertainty are essential to our collective coming of age – and in that sense this is a deeply youthful film – but they are also, in their way, the building blocks of who we become later in life. Those same gasps of punctuation between moments of pleasure are a deep component of his work, and they are made all the more intimate and vulnerable by their nascent status here.