Alfred Hitchcock is considered a visionary and impressive director for good reason. Not only did he create some of the most suspenseful films ever put on screen, but he collaborated with an incredible composer (Bernard Herrmann) on some indelible music, created new types of camera shots and angles with his directors of photography (most notably with Robert Burks), and coaxed great performances out of the many actors and actresses that had the pleasure of working with him on his movies. He is beloved and revered for the mark he left on cinema.

Obviously, to discuss which of his movies is his best would inspire furious debate. For years, the consensus pick was Psycho, Hitchcock’s tense puzzler of a movie that ends with one of the most well-known twists of all time. Some may have stumped for North by Northwest, with its charming leads and its espionage-lite plot. Northwest is Hitchcock at his most spry, juggling a twisty plot, showy set pieces, and a romance with aplomb.

And there were probably even votes for The Birds, arguably Hitchcock’s most dated film. Though once considered a horror film, it feels more like a campy parody in 2017. And a passionate crowd would have also lobbied for Rear Window, Hitchcock’s taut thriller that riffs on the idea of paranoia come true.

When the American Film Institute (AFI) released its first list of the 100 Greatest American Films in 1998, Hitchcock had four films make the list: Psycho came in #18, North by Northwest came in at #40, Rear Window came in at #42, and the haunting and atmospheric Vertigo followed at #61. Hitchcock was one of the most well-represented directors on the list, indicative of his critical standing and influence on cinema.

AFI decided to revisit their list in 2007, revising and re-ordering based on a critical reassessment of all of the previous films. Something interesting happened with Hitchcock’s oeuvre. Psycho rose in esteem, gaining four spots and ending up at #14. Rear Window, a victim of a number of movies joining the list and a few others moving up, descended six spots to #48. North by Northwest was a victim of the same, dropping below Rear Window to #55.

Most notably, though, Vertigo, originally the lowest rated of the four, in the nine or ten years that had elapsed, came to be considered Hitchcock’s classic, rising an incredible 54 spots to #9, ahead of The Wizard of Oz and one spot below Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.

What was behind the rapid rise of Hitchcock’s most moody movie? (Which also came in at #1 in British magazine Sight and Sound’s 2012 poll.) Mostly, in a critical re-evaluation of Hitchcock’s career, critics and cinephiles have realized what a profoundly ahead-of-its-time movie it is. It’s moody, it’s romantic, it’s insane, it’s gorgeous, and it’s one-of-a-kind. Below are the eight reasons that Vertigo is Alfred Hitchcock’s unequivocal greatest film.

1. Jimmy Stewart

The star of such films as The Philadelphia Story, Harvey, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It’s a Wonderful Life is famous for being a humble, generous Everyman in the majority of his films. Not unlike Tom Hanks in our modern era, Stewart was seen as a real-life “good guy” and parlayed that impression into a onscreen persona of kindness and virtue.

Hitchcock was one of the few directors to exploit the audience’s perception of Stewart. In four collaborations (Rope, Rear, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Rear Window, and Vertigo), Hitchcock coaxed scarier, rougher, and–ultimately–BETTER performances out of Stewart.

In Vertigo, Stewart’s John “Scottie” Ferguson transitions from the Jimmy Stewart audiences had loved in many previous films (early on, he channels that same “aw-shucks” quality he trafficked in) to an obsessive, almost unhinged man who inadvertently forces the women he loves to plummet to her death.

Witness the chilling final scenes as Scottie drives Kim Novak’s Madeleine/Judy to the tower where she supposedly died earlier in the film. His chilling monotone voice, his expressive eyes, and his chilling grin all highlight a scarier and subtler Jimmy Stewart. The audience must believe that the man they knew as George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life has become a powerful provocateur.

As the scorned lover, Stewart must show how his obsession has become something greater: a desire for revenge. Hitchcock and Stewart both seem to understand intuitively that the scene’s efficacy is enhanced by the contrast between Stewart’s consistent real-life persona and the more enigmatic compexity of his Vertigo character.

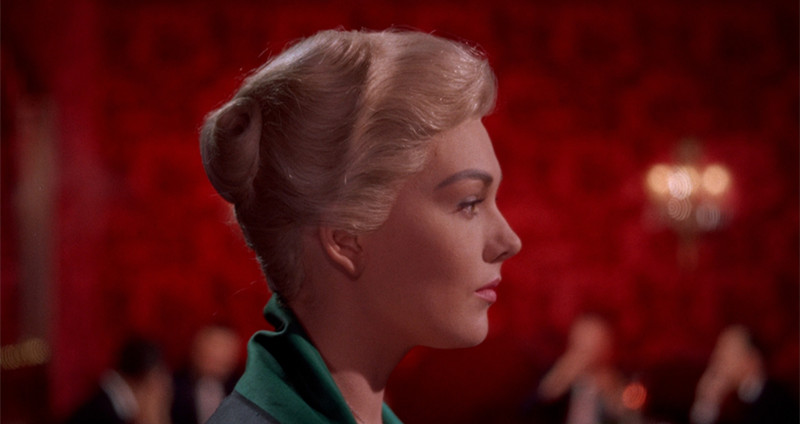

2. Kim Novak is dynamically sexy

In a performance that requires her to be both alluring and aloof in equal degrees, Novak is ravishing and sexy and, ultimately, heartbreaking. Often, the sexiest performances are those that call the least attention to their sexiness. Though Kim Novak is classically beautiful, the role requires her not to showcase it overtly, but nonetheless understand the magnetism she naturally exudes.

Especially in her first few scenes as Judy, when she must repeatedly rebuff the advances of Scottie by making allusions to the way men have treated her throughout her life, Novak portrays the grit and innocence of the character in a way that makes viewers want to protect her while simultaneously understanding that she can absolutely take care of herself.

Likewise, early in the film, she must appeal to Scottie (and the audience) in scenes where she simply sits there, staring, or walks stoically through gardens or on the street.

Yes, her beauty plays a big role here, but it’s the depth of expression in her eyes and the unassuming way in which she carries herself that makes her so attractive and compelling. Hitchcock understood that she would demand attention simply by being there.

However, without the deeper levels of her performance, she would have simply been a pretty face and not the woman that turns Scottie/Jimmy Stewart into a scary, tense, disturbing version of himself.

In the final scenes, as Scottie angrily forces Madeleine/Judy up the tower stairs, viewers are torn. Scottie sees her as a heartless vixen and the audience can understand the excessive infatuation that she inspires because they feel it too.

3. The brilliant and eerie camera work and lighting

Hitchcock is known for having created new camera techniques and shots with his DPs throughout the years. Here, Hitchcock and his (oft) DP Robert Burks create striking compositions, most notably when Novak’s Judy emerges out of a fog like a ghost, dressed as Madeleine again because Scottie made her. It’s a wonderful visual representation of Scottie’s feelings, as Madeleine is literally coming back from the dead in his mind.

Hitchcock and Burks also make use of green lighting to suggest a bit of an off-kilter feel for scenes. Often, light streams in through green curtains in Madeleine/Judy’s home, bathing Novak is soft green light and giving her face an ethereal glow. The color green can represent many things: nature, fertility, ambition, greed, and jealousy.

Here, it seems to give Madeleine/Judy an otherworldly feeling. For both she and Scottie, this is an unbelievable turn of events. Not only that, but it will soon sour. With the camera work and the lighting, the audience is kept on its toes, wondering when the other shoe will drop.

4. The evocative score

Bernard Herrmann’s score is haunting. It has served as the inspiration for countless other composers. It has to evoke both the romance and the obsession and the confusion of Vertigo and manages to do all three and more, often at the same time. The movie is full of scenes where characters are simply watching other characters or riding in cars together or walking. Herrmann’s score manages to give each of those scenes a specific mood.

Two specific car-driving scenes highlight this especially well. A little over halfway through the movie, Scottie and Madeleine drive to the tower where she eventually “dies” and Herrmann’s lush score suggests both the intense love that they feel for one another AND foreshadows the terrible events that are coming.

Then, when they are returning to the tower at the conclusion of the film, before Madeleine/Judy dies for real, Herrmann’s score still carries an undercurrent of the song from earlier, reminding us of the strong feelings they have for one another. This time, however, the music underlines the creepy demeanor that Scottie is showing toward Madeleine/Judy.

Though Scottie’s instincts are entirely correct, he has turned into somewhat of a monster. The betrayal of Madeleine/Judy hurts him so much that he transforms. Herrmann’s score is such that it doesn’t want us to focus only on that transformation, but remind us of everything that has come before.

The music is so nimble that it can be all things at once. It’s a great gift Herrmann possessed and one that is on display more prominently in Vertigo than in any of his other scores.