There always seems to be the chosen few or, really, THE ONE in any movement of film history. With Italy’s Neo-Realist movement it was Bicycle Thieves. New Hollywood will always be identified with the film that started it all, Bonnie and Clyde or, perhaps, The Godfather. Out of the Past seems a perfect illustration of film noir. Singin’ in the Rain is the epitome of the Hollywood Musical. Though the indie revolution of the 1980s and 90s produced some memorable films, is there any better remembered than Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994)?

Anyone who was around and at all aware of film in 1994 and, truthfully, the years just thereafter, knew and had an opinion of Pulp. It came out of virtually nowhere, altered lives, careers, and directions (literally) and was a true game changer. The irony is that it was both very new and pretty old. It was original and yet derivative.

It started careers and put new life into old and seemingly dead ones. At a moment when it looked like few passionately cared about the movies anymore, it had many people talking (and make no mistake, its high level of violence had some talking in negative directions, always a sign that a film has said something).

When the iconic film critic Pauline Kael, then retired due to poor health, was interviewed in 1994, the big question was what were her thoughts on the two big films of the year, Forest Gump and Pulp Fiction (she hated Gump and said that she enjoyed Pulp tremendously but warned that it was in danger of being “taken too seriously”).

Though its production company, now in existence in name only, had bigger hits at the box office and its creator has gone on to make other memorable films, nothing else was ever quite like Pulp. Why? The following brief list tries to shoot out a few theories as to the why of it all.

1. Miramax

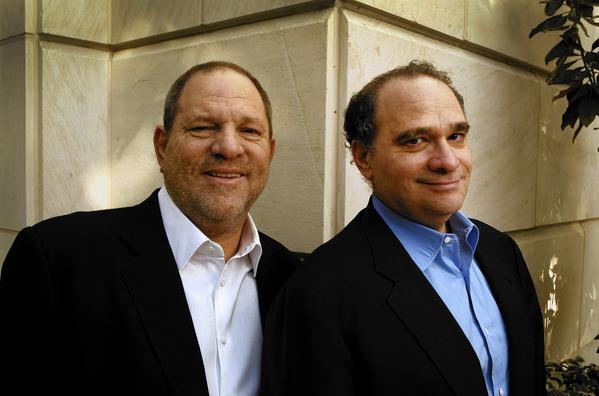

Every jewel must have a fine setting and, truly, the indie movement in American film making would not have been the same without Miramax. With a moniker derived from the given names of their parents (Miriam and Max), the company was the brainchild of brothers Harvey and Bob Weinstein. Like its most iconic film, Miramax was both old and new.

The company was run much like the old Hollywood studios in that quality and economic concerns were balanced rather evenly. The brothers wanted to make money, surely, but they wanted to make good films that would make money honestly by giving the audience its money’s worth and saying something. In that sense Harvey Weinstein, no gentle pushover to be sure, was very hands on. The new part came in with the type of films the company chose to make.

The brothers realized that the people who might come to the films they wished to present were young, hip, progressive and wanted to see films, even lighter films, which had an edge to them. As with virtually all companies making indies (and, sadly, most did not survive financially over the long run), Miramax realized that big stars, franchise films, and huge budgets weren’t where it was at for their viewers.

Though Miramax films never looked cheap (and advances in technology allowed even lower budget films to look good by that point in time), they never cost so much and, if a big star did choose to work in one, they did so at a reduced salary for the prestige of it all. Without many of the things mainstream Hollywood deemed essential to box office success, Miramax and other indie producers had to offer quality and creativity in order to get somewhere.

Harvey Weinstein had believed in Pulp Fiction from the get-go, supporting it all the way, including keeping it out in theaters with heavy promotion until it hit the $100 million dollar mark, something more commercial films did frequently (though it was a first for Miramax).

Pulp might have found a home at another company but, even then, Miramax attracted good people and that helped a little known film maker (at the time) to make something that looked and felt most professional. Miramax was, sadly, absorbed by Disney and the brothers eventually ousted.

They rose like a pair of phoenixes to create the highly successful Weinstein Company and have gotten a lot of Oscars (in fact, the Oscars were permanently moved forward to February mainly due to the company’s aggressive Oscar campaigns, which the Academy hoped to shorten). However, they have never had another Pulp (and probably won’t) and the current company doesn’t still represent that same magical time.

2. The Script

Though some film makers like to make it seem as if they could improvise on the spot and make a great film, the word, one way or another must come first. Though Quentin Tarantino is primarily thought of as a remarkable director in terms of being a stylist, innovator and screen personality, it’s telling that the two Academy Awards he has won to date have both been for his screenplays. Yes, he knows about visuals (much more on that later) but he knows content as well.

A typical Tarantino script is a treasure chest of characters, dialog, plot twists, and so many things that can help to make a movie special. Some of these things will come later in the list but one thing to consider in this entry is that he knows, as few others today do, how to structure a script and play with time line and perspective in creating interest in his film’s stories.

Tarantino famously has stated that his education largely came from working in an expansive video store as young man (surprisingly already a lost experience to the current generation). Many have worked in such a setting without garnering such insight so it’s obvious that the young Quentin had the taste and insight to find films which would teach him something.

Though he has never stinted on talking about influences, he hasn’t especially pointed up how Stanley Kubrick’s early caper film The Killing affected his work. That film and its shifting time structure showed up in both Tarantino’s excellent debut, Reservoir Dogs (1992) and in Pulp. Viewers don’t really concentrate on it but Pulp actually takes place during principally two eventful days within the frame of a week.

The structure is the traditional play/screenplay three acts but the way the time line is distributed is this: story one takes place during the day and evening of a rather jam packed period (professional hit, drug purchase, night on town), act, after a prologue set some thirty years in the past, two late evening and the following day a few days after the first act (and a most significant event happens to a major character from act one who is a minor player in act two), act three goes back to the day of act one but is set during the time an ellipsis during act one omitted.

When act three takes place the pre-title prologue set in a coffee shop with two characters not seen in acts one and two suddenly make sense and set the stage for the major events of act three after an amusing episode tying up another thread from act one.

This sounds tricky and it was challenging for some viewers but the time shift pays off emotionally since the viewer, based on what happened in act two, knows things about the future the main characters in act three don’t and this deepens much of what is said and done involving the characters. All of this could have been so confusing or pretentious in the wrong hands but Tarantino and then-partner Roger Avery pull it off like seasoned pros.

3. The Cast

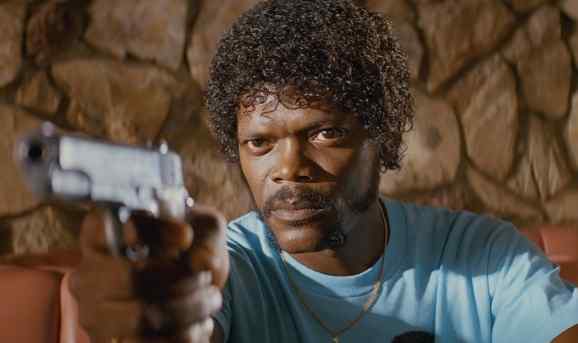

No one would ever say that Quentin Tarantino is anything less than adventurous in casting his films, but he has method to his madness. He prefers two kinds of actors in his films principally and both kinds have to possess presence and bring subtext to his films. Firstly, he likes to find the kind of character actors people often say don’t exist anymore, usually people who haven’t been that well known until Tarantino discovered them.

Samuel L. Jackson, so superb as Jules in Pulp and in almost every film the director has made since, Christophe Waltz, who has won two Oscars for the two Tarantino films in which he has appeared (Inglorious Basterds, 2009 and Django Unchained, 2012), and Uma Thurman, who seemed something of an also-ran until the director turned her into first an Oscar nominee (for Pulp) and then a goddess (the Kill Bill films in 2003 and 2004) are all examples of this type of casting.

However, the casting which often receives the most comment is the star casting in Tarantino’s films. Now many film makers cast stars for box office but no one casts quite like Tarantino. If the star is somewhat current such as Jamie Foxx or Leonardo DiCaprio (both in Django Unchained) or Brad Pitt in Inglorious Basterds, he will cast them in unusual roles.

However, he has an absolute thing for people, who may not… well, have worked much lately and who are ripe for comeback status. In Reservoir Dogs he brought back Hollywood Golden Age tough guy Lawrence Tierney. In Jackie Brown (1997) he brought back, after decades of seeming inactivity, 70s blaxplotation star Pam Grier and late 60s indie star Robert Forrester (Oscar nominated). 70s cult star David Carradine had one great last bow as Bill in the Kill Bill films.

There are others, but the king of them all belongs to Pulp. John Travolta had been hot, hot stuff in the late 70s with his seminal performance in 1977’s Saturday Night Fever and the next year in one of the decade’s big box office hits, Grease. Unfortunately, things had gone less well thereafter and by the time he was cast in Pulp as hip but drugged up and none too bright hit man Vincent Vega, he had been reduced to doing a series of films about a talking baby.

Everyone thought that Tarantino had lost his mind casting such a has-been but the memories of an eternal cinephile burn bright. The joke was on the nay-sayers and Travolta scored an Oscar nominated triumph which reignited his career (though he chose to go commercial and has never worked with Tarantino again).

Added to the trio of Oscar nominated performances were such on the money, yet largely underappreciated actors as a Bruce Willis, Ving Rhames, Tim Roth, stage/TV actress Amanda Plummer, Eric Stoltz, Rosanna Arquette, Christopher Walken, early Tarantino encourager Harvey Keitel, and…well, the director himself, who is always colorful in a big jerk kind of way when he does cameo parts in his own and other people’s films (and he should just do cameos since what he does is amusing but nothing to dwell upon).