Next year will be the 50th Anniversary of one of the greatest films ever to be put on the silver screen, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Made in 1968, Kubrick’s tour de force is an iconic piece of modern media art, with its immeasurable influence still being felt on contemporary directors and filmmaking ideologies even in the 21st Century.

With ground-breaking visuals, an instantly recognisable soundtrack and several avant-garde cinematic techniques, 2001 is a genuine masterpiece of cinema, and for that reason (as well as several others), is the greatest Science Fiction film of all time.

1. Subversion of Classical Cinematic Techniques

After dominating American silver screens for the previous four decades, the cinematic style of “Classical Hollywood” filmmaking was finally beginning to decline towards the end of the 1960s. Films such as Easy Rider (1969) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967) signalled the start of a new era, and with it came a complete reformation in the American approach to cinema.

Following along in this progressive movement, whilst also being completely unlike anything in Hollywood at the time, was 2001. Kubrick’s paragon is generally considered to be a part of the New Hollywood brand of filmmaking, however it is arguable that 2001 was still largely unmatched in America in its subversion, distortion and sometimes outright rejection of the previously indispensable cinematic rules and techniques that dominated Classical American cinema.

For example, the narrative logic of Classical Hollywood cinema would often follow the psychological processes of a single central protagonist, often attempting to reach a final goal or conclusion. This structure of a beginning-middle-end linear narrative, the norm at the time, is largely abandoned by 2001.

The only recurring “character” in the 3 main sections of the film – the enigmatic, other-worldly black Monolith – has no emotion, no action, and certainly no psychological process to follow. This not only means the classic “goal-orientated” narrative is deserted, but also that the audience cannot truly gain any emotional connection with any character, creating a distancing and meditative effect that allows the viewer to genuinely reflect on the film for themselves, rather than from the point of the view of a protagonist.

Furthermore, the use of cinematic time in 2001 is warped to a degree so extensive and far-reaching that the audience witnesses not just two, but three stages of human evolution in under two and a half hours. The film begins with primitive apes learning how to use bones as weapons, whilst the ending looks beyond the human race at a species even more advanced than ourselves – the “Starchild”.

In a single jump cut, Kubrick moves from an ape throwing a bone into the dry African sky to a Pan Am Spaceplane, moving through outer space millions of years later; possibly the most ambitious jump cut in cinema history. This ambition would have never occurred in Classical Hollywood, with continuous, linear and uniform timelines (flashbacks were occasional) being the standard.

There are several more examples of the ways that 2001 rejected the traditions of Hollywood filmmaking, and the ways in which Stanley Kubrick consistently used these subversions to the advantage of the feature. However, by the abandonment of two key classical cinematic rules, the logic of narrative and time in a film, it shows how far Kubrick was willing to go to achieve his vision, and – by the success of the film – how adroitly he executed it.

2. Strong Themes of Existentialism and Technology

Those who attempt to criticise Stanley Kubrick often argue that his films lack a genuine emotional depth, making his whole filmography appear cold and distant, regardless of technically proficiency. There may be some truth in this argument – from Spartacus onwards his films began to have an increasingly nihilistic view of the society around him – however in 2001, it must be stated that the film’s lack of emotion (or more accurately, lack of human emotion) is necessary for the rest of the films major themes to be fully explored by Kubrick.

From the moral dilemma of A Clockwork Orange to the duality of man in Full Metal Jacket, the philosophical beliefs of Kubrick, shown throughout his career, point towards the existentialist-nihilist end of the spectrum. This is presented consistently, and with great significance, throughout 2001.

The tenets of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, as well as his belief of the Ubermensch, can be recognised in the events concerning the Apes, Bowman and the Starchild – man’s final evolutionary step towards the “Supermen”. This development into higher life through Bowman’s own individual acts of will is strongly existentialist in its conception, giving meaning to his own life through the virtue of authenticity.

In addition to the possible philosophical connotations, the relationship between the human race and technology is one of the more obvious themes of 2001. The HAL 9000 Computer, an effectively perfect entity, is put at odds with Bowman and Poole (the human race) when it becomes aware of the true importance of the Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter.

This raises the question, can we really trust technology? Will technology, if sentient enough, sabotage the human race in pursuit of its own gain, just as HAL does? In the context of 1960s America where the global “Space Race” dominated the news, and even today with the development of robots and potential A.I., these questions remain totally and unequivocally relevant.

Nietzsche and technological progress are two of the many thematic influences on 2001, and also two of the most important. Through the rejection of emotion and character development, Kubrick allows these themes to be fully investigated, removing all ulterior motives from Bowman and HAL to reduce them right down to the basic existential human purpose; survival of the individual, and exceeding that, evolution.

3. Ground-breaking Special Effects

Special Effects (SFX) in 21st Century cinema, with the aid of CGI, have reached unprecedented levels of accuracy, detail and creative reverie. Jump back nearly 50 years, and the SFX team working on 2001 – including the acclaimed SFX supervisor Doug Trumbull – were making cinematic history as they put together what was then ground-breaking visuals, paired with unparalleled scientific accuracy.

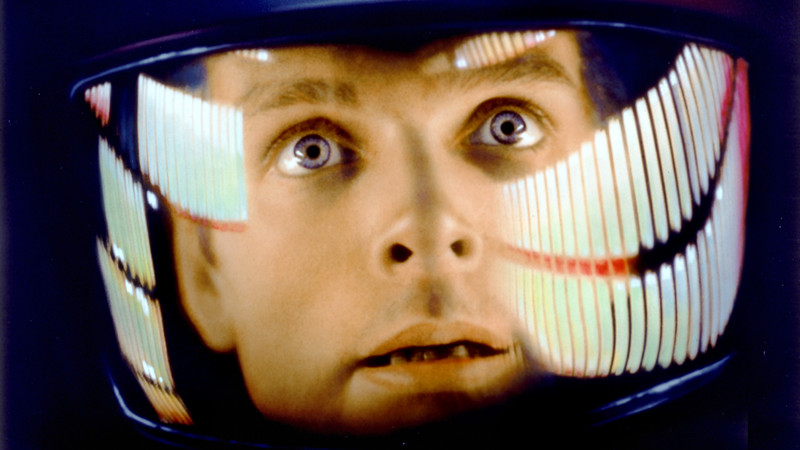

Trumbull, one of four SFX supervisors on the film, was responsible for the development of slit-scan photography on the set of 2001. Now fairly common in use, at the time it required a uniquely adapted custom built machine, and Trumbull’s utilisation of it resulted in one of the most iconic and essential scenes in the film; Kubrick’s transcendental “Stargate” sequence.

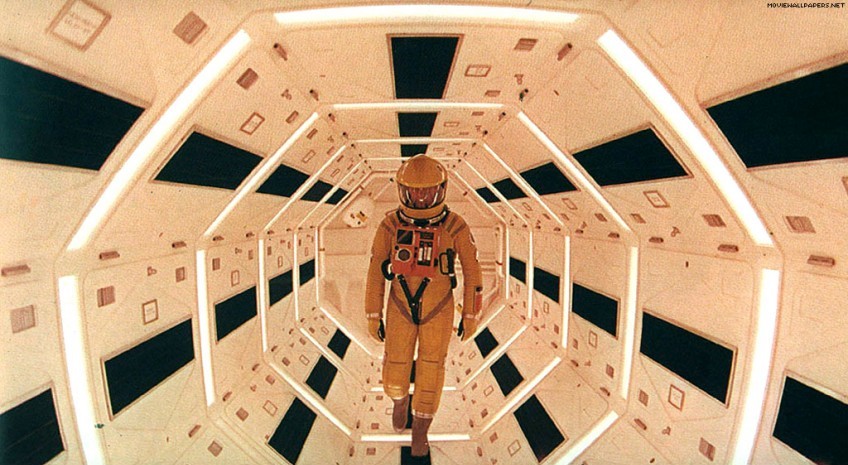

Slit-scan photography may have been the most truly original effect employed by Kubrick, Trumbull and Co., however many other SFX in 2001 are just as impressive in their ambition and scope. The rotating sets (Kubrick had a 30-short-ton Ferris Wheel made for $750,000), zero-gravity illusions and use of detailed miniature spacecraft models all contributed to the fantasy Science Fiction element of the space epic, aweing 1960s audiences in the reality of its magnitude.

Kubrick won his only Oscar for the Visual Effects of 2001, and deservedly so. The work of Trumbull and other SFX supervisors must also not go unmentioned in the legacy of the feature, with their contributions helping to create visuals that were unmatched in quality and originality at the time of the film’s release, and still stand up today as some of the best SFX in Science Fiction cinema history.

4. Bold and Challenging Ambiguity

Ambiguity in cinema, and art in general, can be both a blessing and a curse. Often in Hollywood and mainstream cinema, ambiguity is rejected in favour of literal narratives and themes, appealing to the masses and drawing in as large an audience as possible.

Although there is certainly nothing wrong with this, it is arguable that an element of ambiguity can allow individual viewers to interpret the work for themselves, therefore evoking a more genuine and personal emotional response to a film. This ambiguity, of course, can be taken too far – an incessantly idiosyncratic piece of art can be just as mind-numbing and ineffective as a completely literal one.

Kubrick plays this fine line between literality and idiosyncrasy perfectly in 2001. Linked together only by the constant recurrence of the perplexing black Monolith, the narrative of 2001 is certainly ambiguous, as are its characters. The four central parts of the piece – Dr. Floyd, Bowman, Poole and HAL – are barely characters in the classical sense.

There is almost no emotional connection between the four and the audience, with little being known about any of their backgrounds, opinions or personalities; the closest we get to any true emotion in 2001 is, perversely, from the HAL 9000 Computer, showing one of the most basic human facets – a fear of death.

This abandonment of the classical use of characters allows the viewer to meditatively explore the rest of films events for themselves, which in their own right are ambiguous and largely unexplained.

The “Stargate” sequence, Bowman’s final moments of life, the resulting Starchild – a 20 minute psychedelic rollercoaster with no dialogue, no emotion and no consistency in location or time. This bold conclusion from Kubrick leaves the audience suspended in a mixture of awe and thoughtfulness, pushing them further and further to think about the films meaning for themselves, rather than simply being told what to think.

Some may argue that 2001 is too ambiguous, making it difficult and even strenuous to watch. This may be true, but without films that challenge and provoke the viewer then we will be left with only literal art that does not truly question anything, and therefore answer nothing. This shows the importance of Kubrick’s unapologetic oracle, and the directorial skill it took to execute the work without completely alienating the mainstream.

5. Stanley Kubrick’s Magnum Opus

After becoming concerned with the increasing amount of crime in America, a 33 year old Stanley Kubrick moved to the county of Hertfordshire, Southern England in 1961. Despite being a world away from the shining stars and bright lights of Hollywood, Kubrick, from his Manor in the country, became one of the most respected and successful directors of the era.

A duo of comedies with the legendarily versatile Peter Sellers (Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964)) shot Kubrick into stardom, and by the late 1960s he was gifted with what all directors dream of – complete creative and artistic control, whilst also possessing the stature in the film industry for any feature to be commercially viable.

Kubrick – producing, co-writing and directing the film himself – took complete advantage of this freedom. A demanding perfectionist the vast majority of the time, this independence allowed Kubrick to fully exert the meticulousness of his unique directorial style, creating a work that was, at the time, completely unrivalled in its scientific realism, technological accuracy and special effects.

2001 also marked an artistic turning point for the still relatively young Kubrick – by 1968 he was still only 40, and still had over 30 years of his career ahead of him. Not only did the work venture into a completely new genre Kubrick had previously not employed, but it also marked his first experimentation with colour in film, which he uses with aplomb in the infamous “Stargate” sequence – “the ultimate trip”, indeed.

Furthermore, 2001 signalled the end of Orson Welles’ vast cinematic stature overshadowing Kubrick, with the former’s influence being felt immensely in the earlier stages of Kubrick’s career. Bill Krohn, a correspondent for Cahiers du Cinema, stated – “Nothing Kubrick did after 2001 resembles anything by Welles, because this is when Kubrick began making films that are like no films that had ever been seen, including his own”. This then, shows the utmost importance of 2001 to Kubrick and his legacy, and therefore to the whole of Cinema; with this epic achievement of grandeur and eloquence, Kubrick evolved into a cinematic giant on the level of Hitchcock, Chaplin and Welles.

In an oeuvre of impressive and highly influential filmmaking, 2001 stands above the rest in Kubrick’s filmography as a masterpiece of cinema, Science Fiction and modern media art. Elevating him from the shadow of Welles, 2001 truly etched the legacy of Kubrick into the very framework of cinema history, leaving arguably the greatest filmmaker, and greatest film, to ever be seen.