5. Swingers Slow-Motion Strut (Reservoir Dogs)

This ensemble buddy comedy paved the way for all frat pack and Apatow-vehicles to this very day. Vince Vaughn plays a heartbroken comedian whose friends help repair his heart through concerted womanizing. After finishing a poker game during a night on the town, the friends strut down an alley towards their cars in stylish, slow-motion execution to the song Pick up the Pieces by Average White Band. It’s hard to think of Swingers without evoking this scene.

Unless you’ve never been a connoisseur of independent cinema, you’d know that the slow-mo scene is a direct, conscious rip from Reservoir Dogs, where the six colorful criminals strut down the street after finishing breakfast. In fact, the preceding discussion at the poker table is homage to the Reservoir Dogs discussion in the diner about tipping, only the topic is film—those of Tarantino and Scorsese, to be exact. As you can see, Tarantino’s not only the perpetrator of cine-sampling, but has and continues to supply a deep well of content from which filmmakers can draw for time everlasting.

4. Requiem for a Dream Bathtub Scene (Perfect Blue)

Crawling with unsettling imagery shot through an aesthetic lens, Requiem for a Dream is a film about drug tripping but also a trip in itself. One such scene of stylistic beauty but disturbing content is Jennifer Connelly’s underwater explosion.

From above, we see Connelly’s character lying naked and prostrate in a bathtub. The next shot is underwater; she isn’t moving and we don’t know why. Then, suddenly, she screams. It’s an ejection of pure anguish, muffled by water and punctuated by a splintering soundtrack, stemming from drug-related problems too innumerable to name. The scene is hard to forget, and harder to shake.

Though so perfectly Requiem, the bathtub sequence is taken, shot for shot, from a 1997 Japanese anime Perfect Blue. Darren Aronofsky, Requiem’s director, knew it would be a superb fit, so, to eschew any ambiguity, bought the rights to the movie for the use of one 30-second scene.

Perfect Blue is about an aspiring actress whose entanglement with a demanding role and an obsessive doppelganger distorts reality and drives her insane. Sound familiar? This is where the similarities between Requiem end and Black Swan begin. Perfect Blue director Satoshi Kon acknowledged the appropriation and still regarded Aronofsky’s work with respect. It’s clear the directors are more than just mutual admirers but conceptual twins.

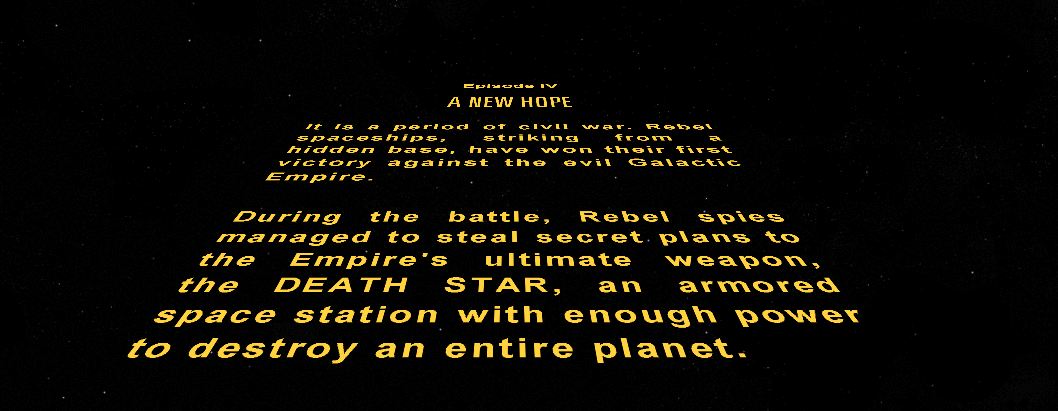

3. Star Wars Title Crawl (Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe)

The trumpets blare and the preamble to the most successful movie franchise crawls across the screen. No title style is more synonymous than this. Through all principal installations of the Star Wars dynasty the titles have crawled in the same fashion, as any variation would be sacrilege. You’d be hard-pressed to find a cinematic technique more iconic.

But it’s not original. Lucas, the classic sci-fi buff, borrowed the style from a golden-age sci-fi staple, Flash Gordon. Flash Gordon was the Star Wars of the thirties and forties: a multi-media empire that enthralled generations of kids with heroic characters and space exploration.

It was 1940’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe where Lucas drew much inspiration. Complete with the epic music, tilt, and crawling text, the introduction to Flash Gordon enveloped the screen in the supposedly revolutionary way Star Wars did 37 years later. But the emulation doesn’t end at the title. George Lucas admitted that in making Star Wars he wanted to “do Flash Gordon,” and he did—all the way to the bank.

2. Boogie Nights Opening (Goodfellas)

The porn film made so well that porn is the last thing one remembers upon finishing. Boogie Nights, Paul Thomas Anderson’s love letter to the industry, begins as a period piece on acid. Winding through a nightclub, the camera tracks the various personalities and situates their characters in the context of 70s debauchery. Few opening scenes set up a movie so perfectly, and it’s the music, atmosphere, and casual voyeurism which meld to make it great.

Those with a keen eye for 90s movies may notice the similarities between the Boogie Nights opening and the Goodfellas Steadicam scene—because they are directly linked. Paul Thomas Anderson admitted this fact. The scene was a tribute to what Anderson and many consider one of the greatest scenes in one of the greatest movies: where the camera follows Henry and Karen through the Copacabana for two minutes of continuous footage with no cuts. It is perhaps the best use of the Steadicam technique in all of cinema, though Boogie Nights makes a solid case.

1. The Matrix Raining Code (Ghost in the Shell)

Red , sunglasses, spoon-bending, suit-clad agents, karate—The Matrix established such weird and rich iconography for the burgeoning cinephile of the Information Age. But, like many of your favorite movies, The Matrix was successful not by employing original ideas, but by packaging existing ideas in a practical and palatable way for mainstream consumption.

Films like Blade Runner, Alice in Wonderland, and Akira laid the stylistic framework for the now-iconic Matrix universe, while wide-ranging sources, from Karl Marx to The Bible, supplied various themes. There were other sources, however, with a more than contingent inspiration, which became unbeknownst architects of specific scenes.

Take the green code, scrolling and replicating quickly across the screen—not only creating programs on which the fictional simulation is run, but creating wonder in the viewers whose perception of reality ceased to be certain. The Wachowskis, Matrix’s directors, never hid their love for sci-fi anime (how could they?) and this is an overt example.

Little known to Western audiences until the live-action reboot of 2017, Ghost in the Shell is a multi-media institution of speculative anime so affecting that the Wachowskis couldn’t help from copying. The raining code bears striking resemblance to the opening credits of the 1995 movie, where the names materialize in the same coded fashion as in The Matrix—green tint and all. If you consider Quentin a DJ of ideas, The Matrix is an orchestra.