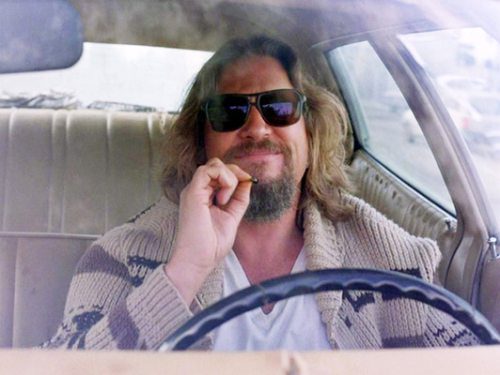

6. The Big Lebowski

The Coen Brothers (Joel and Ethan) certainly know how to spin a yarn: from the frenetic fable of Raising Arizona to the somber drama of No Country for Old Men, the Coen Brothers write and produce films both left-of-center and deadly serious. The Big Lebowski is firmly set in the former category, following the misadventures of a lackadaisical stoner (Jeff Bridges as Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski) in 1991 Los Angeles.

A shaggy-dog detective story unravels as The Dude is mistakenly targeted by a group of nihilists for ransom money. Since one of the nihilists soiled his rug (which really tied the room together), The Dude sets out to find the actual Lebowski, a wealthy philanthropist, for remittance.

Instead, the “real” Lebowski charges The Dude with the responsibility of handling the ransom payment and recovering his wife safely. So The Dude, woolly and bleary-eyed as ever, rambles through the plot–which includes his bowling team advancing to the finals, a bowling-themed dream sequence accompanied by Bob Dylan’s “The Man In Me.” and a sideways romance with Lebowski’s nutty artist daughter. Sound crazy? It is, in the most spectacularly amusing way.

Released in 1998, The Big Lebowski received mixed reviews, with many critics not sure what to make of the film. Although obviously expertly done, some were surprised to find that the same duo that just produced the Academy Award-winning Fargo would choose this wild tall tale as their follow-up. Turning a small profit, it was seen as yet another odd entry in the ever-expanding cinematic universe of the Brothers Coen.

When Awards season came around, the duo that were nominated for seven Oscars just two years before were nominated for none. But history would prove the long-lasting success of The Big Lebowski: upon entering the video market, the film became a bona fide cult hit, with its characters and dialogue going memetic just before online memes were a phenomenon. Its offbeat humor, likable and laid-back protagonist, and genuinely weird tone endeared it to film fans and has since has become one of the Coen Brothers’ most popular films.

As for the missed nominations: surely this film’s Raymond Chandler-esque story soaked in patchouli oil and buzzed by a contact high was worthy of a Best Original Screenplay nomination, particularly in the same year such middling fare as Shakespeare In Love walked away with the prize, while Jeff Bridges playing a middle-aged hippie relic would have been a better choice for Best Actor than Roberto Benigni’s maudlin performance in Life Is Beautiful.

Even a Best Art Direction nomination would have served as a fitting tribute for such a stylized film. But Oscar nomination or no, it’s not very Dude-like to worry about such matters.

The film is still recognized as a contemporary classic, and even without the prestige of an Awards nomination generations of film lovers can look forward to spending a few fun hours watching the pot-addled Lebowski figure out just what the hell is going on. In other words, The Dude abides.

7. Groundhog Day

A cantankerous TV weatherman stuck in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania for its annual Groundhog Day ceremony finds himself reliving the same February 2nd every day he wakes up. For maybe thirty years’ worth of days, Phil Connors (played by Bill Murray) is awakened by the ever-irritating “I Got You, Babe” by Sonny & Cher on his radio alarm clock, doomed to repeat the exact same day over and over, only to wake up the next morning without the events of whatever may have transpired (including killing himself multiple times) to have no effect or even be remembered by anybody else around him. Trapped, he eventually realizes that he must somehow become a better person to possibly escape this never-ending loop.

The film’s brilliant conceit is only matched by Murray’s signature world-weary performance: although initially shocked at what’s happening to seemingly only him, Phil embraces, and then despairs, at his circumstance of being stuck in time before finally discovering that there must be something greater at stake for this anomaly to be occurring to him.

It’s a wonder to watch, considering how bizarre the premise is, as Phil makes a concentrated effort to transform himself from a dour and angry individual into the most likable, charming man on the planet. Between the brilliant jokes that come from such a conceit to the nihilistic abandon Phil finds himself eventually embracing, the film (directed by the late Harold Ramis) keeps its rhythm and focus in lock-step with the premise, making it an off-beat fantasy that is rarely seen in cinema.

Released in 1993, Groundhog Day was both a critical hit and a solid earner at the box office. However, it may have befallen the same fate as many films released early in the year (this being released on February 12th) by not being remembered by Academy voters by the time ballots are cast later in the year. Another thing against it was its status as a comedy, a genre which is traditionally not upon looked favorably by the Academy.

Which is unfortunate, as it’s a brilliant movie: between Murray’s bemused performance as a man trapped in time to the complex original screenplay by Danny Rubin and Ramis to the increasingly dicey continuity that its editing department had to uphold, it’s a masterpiece of comedy cinema.

Instead of being nominated for Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor, or Best Editing, films that were favored in these categories included the tepid Four Weddings and A Funeral for Best Original Screenplay, Nigel Hawthorne for Best Actor for the period piece The Madness of King George, and Speed (SPEED!) for Best Editing.

Unless Academy members can relive the same day over and over in 1993, it seems unlikely that Groundhog Day will have ended up with any nominations, even though it certainly deserved at least a few that year.

8. We Need to Talk About Kevin

A grief-stricken mother lives in isolation and is tormented by the world around her after her son commits a sadistic massacre at his school. Not exactly the feel-good story of the year, but its depiction in We Need To Talk About Kevin is not about feeling good; its impact if found in the horrifying tragedy of the situation. This film details the heart-rendering turmoil that follows such a personal disaster.

Starring Tilda Swinton as said mother, rather than bombastic emoting, she plays the internally tormented mother carrying the the pain and stigma of her still-living son being publicly regarded as a monster. While strangers physically assault her in public, people vandalize her front porch with red paint, and coworkers single her out as a less-than-human target, Swinton quietly drifts through her life and takes this abuse like a martyr.

As a heavy drama that addresses the personal aftermath from a school massacre, survivor’s guilt, and the slow process of redemption after such tragedy, We Need to Talk About Kevin necessitates some buy-in from its audience since this is difficult material to confront.

However, under the poetic direction of Lynne Ramsey and its masterful editing, We Need to Talk About Kevin, released in 2011, is a sterling example of “show, don’t tell,” as the major reveals of the plot are presented through images rather than dialogue-heavy exposition.

The mood and tone of the film is related through scenes that define the characters, such as Swinton’s shouting frustration at her colicky baby or in the dizzying frenzy of an angry mob shouting at her son as he’s led from the school post-massacre while he coldly glares at his mother.

With its artistry and dynamic performances, surely this film should have garnered some Academy nominations. Instead, it was shut out completely, receiving zero nominations in any category. This is difficult to comprehend, since the film features a masterful turn by Swinton and brilliant cinematography and editing.

In a year where Hugo won Best Cinematography and Glenn Close was nominated for Best Actress for the relatively obscure film Albert Nobbs, we need to talk about what the criteria is for nominations by the Academy.

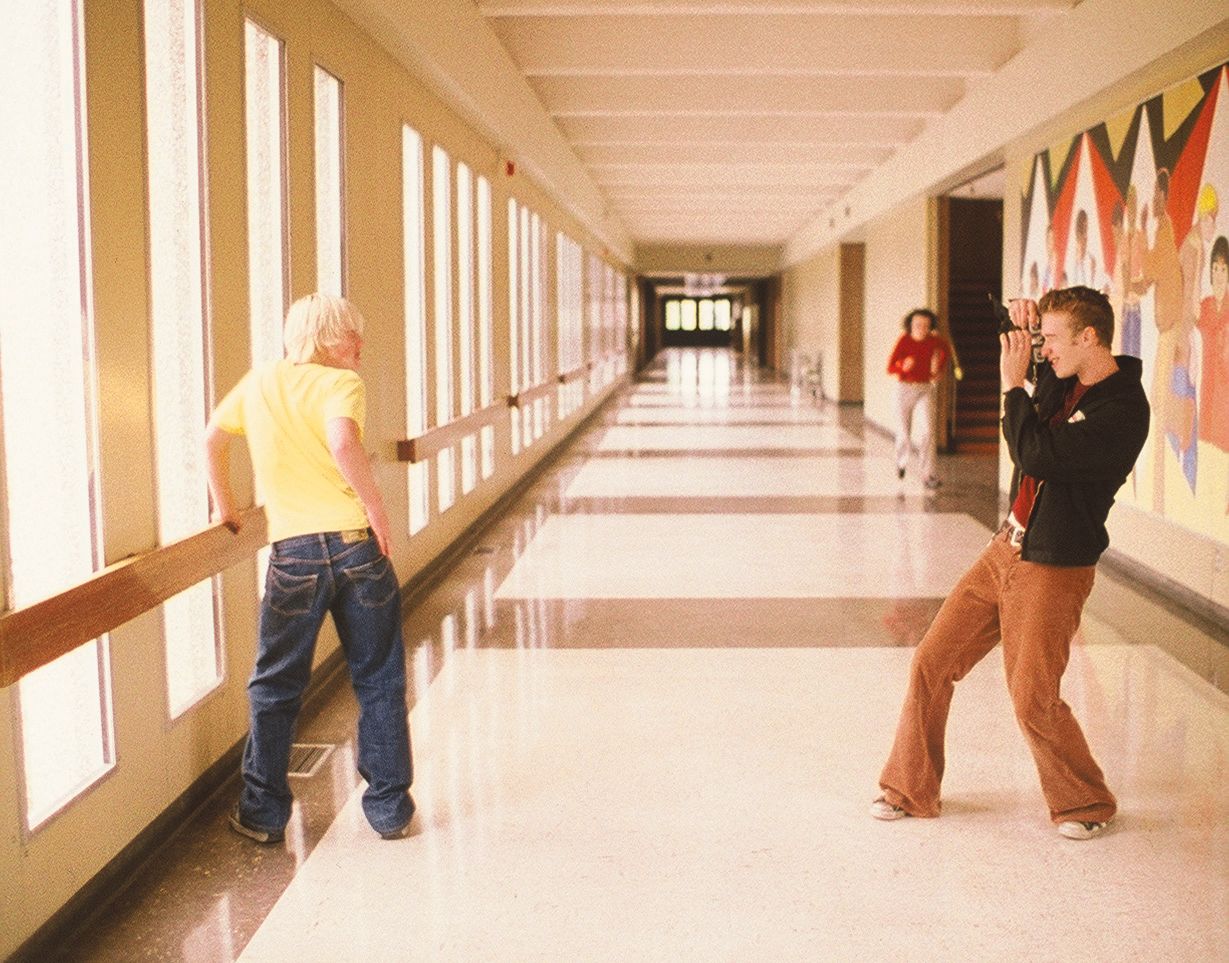

9. Elephant

Along the same lines as the previous entry but taking a more elliptical approach to the subject, Gus Van Sant’s Elephant turns a dispassionate eye towards the event of a school shooting. Part of Van Sant’s “Death Trilogy” (started with Gerry in 2002 and ending with 2005’s Last Days), this controversial film was released just four years after the Columbine Massacre and closely parallels that event.

Following two alienated students who plan and carry out a shooting spree at their high school, the film offers little in the way of explaining why these young men would inflict such violence or what could have been done to prevent the tragedy; it simply depicts the events as they unfold.

Critically praised, it was awarded the Palm d’Or at Cannes and was a success outside of the United States. But American audiences weren’t impressed, and it grossed barely half its budget domestically. Although artistically shot in Van Sant’s signature minimalist style and effective in relating the senselessness of such acts, perhaps it was a case of being “too soon” for American audiences.

Between the Columbine Massacre to the release of Elephant, 23 separate school shootings occurred in the country and there were few answers on how to combat the situation; but one could argue that during this time a discussion of school shootings was an important one for the American public to engage.

Nominated for no Academy Awards in a year when feel-good fluff like Seabiscuit and the fantasy epic The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King dominated nominations, both America and the Academy were more interested in escapism instead of discussing the elephant in the room.

10. Melancholia

But let’s move on from the depressing topic of school shootings and talk about the end of the world instead. More specifically, the end of the world due to a rogue planet that smashes into Earth, obliterating all life.

At least this is the predetermined destiny in Melancholia, Lars von Trier’s 2011 film starring Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg. While its ending is never in doubt, what makes the film fascinating is watching how two very different sisters–Justine (Dunst) and Claire (Gainsbourg)–deal with the imminent end as they (and everyone else) know it.

While initially paralyzed with depression (the titular Melancholia, of which the rogue planet is also named), by the end of the film Justine has found a tranquil sort of peace; meanwhile, her ostensibly sensible sister Claire’s life quickly disintegrates as her recent marriage almost immediately breaks apart at the seams and she begins panicking about the end of the world.

However, this is an oversimplification of the complex tapestry von Trier weaves in Melancholia: the symbolic imagery and recurring motifs at play, combined with the carefully orchestrated synchronicity between the cinematography, editing, and music (which heavily employs Richard Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde”) make it perhaps von Trier’s most beautiful film. Even this is knowingly deceptive on the filmmaker’s part, as the beauty of the film is grotesque considering its inevitable conclusion.

Dunst’s performance was singled out for universal acclaim and she was awarded Best Actress at Cannes that year. The film was also held in high regard by critics, who agreed that Melancholia was an impressive and impacting film, landing on many “Top 10” lists at year’s end. But not one Academy Award nomination was bestowed on what was possibly von Trier’s most artistically successful film.

Why it was ignored by the Academy remains a mystery, but one possible influence was the press conference held directly after the film’s debut at Cannes, where von Trier told a poorly worded joke where he said that he agreed with Adolf Hitler and was himself a Nazi. This led to him being physically banned from the rest of the festival that year and created a certain amount of bad press.

Although Melancholia would go on to be an arthouse hit domestically and was voted by the US National Society of Film Critics as the third best film of 2011, by the time Awards season rolled around not even Dunst’s masterful performance would get a nod from the Academy. Sometimes even bad publicity can be more of a disaster than the end of the world for a film.

Author’s Bio: Mike Gray is a writer and academic from the Jersey Shore. His work has been featured on Cracked and Funny or Die, and he maintains a humor film recap blog at mikegraymikegray.wordpress.com.