Self-reflexive cinema has been around since the early years of the medium. In a couple of words, self-reflexivity isn’t a genre per se but an artistic choice by the filmmakers in which they make their narrative aware of their nature in order to either question or critic the process of filmmaking.

Hence, from the silent era to today’s cinema, self-reflexive films have always been considered unconventional or avant-garde due to their focus on filmic discourse. Whether it be making the audience aware of the moviemaking process through film language, or purely making a film about filmmaking, self-reflexive cinema motivates intellectual interaction with the film.

That said, there has been numerous films produced throughout the history of cinema that are considered self-reflexive. However, only a handful of them truly captured the essence and capacity of its devices for revolutionary or critical purposes as well as the films that follow.

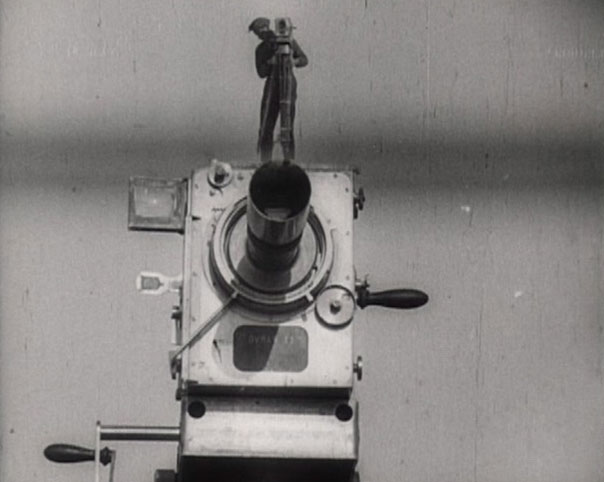

1. Man With A Movie Camera

Released when the silent era was coming to an end, Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man With A Movie Camera is nonetheless considered one of the most revolutionary and influential film of that period. It is a movie, as the director clearly states at the beginning of the picture, that doesn’t have any inter titles nor story— as it aims at creating a truly international language of cinema based on its absolute separation from the language of theatre and literature.

In other words, Man With A Movie Camera is composed of a series of images that, at first viewing, don’t seem to have any purpose. However, they have a distinct pattern and meaning since every shot is either preceded or followed by a secondary shot explaining and demonstrating the procedure involved in capturing the primary image.

In addition, Dziga Vertov intercuts images of industrial machinery throughout the film as a representation of the editing process. Hence, when viewing Man With A Movie Camera, the audience is both witnessing the process of it being shot and edited.

That said, besides being the first true film about filmmaking, Man With A Movie Camera is also notably known for its groundbreaking introduction to unconventional, for the time of its release, cinematic techniques such as, among others, split screens, fast motion and dutch angles.

2. 8½

One of the most reputable film amongst critics, Federico Fellini’s 8½ is nothing short of a masterpiece. Released in 1963, it stars the director’s long time collaborator and diegesis alter ego Marcello Mastroianni as its protagonist named Guido, a proclaimed director suffering from creative block. Hence, 8½ delves into Guido’s unconscious as he wanders through reality and fantasy, trying to figure out the meaning of the film his cast and crew is so eager to start shooting.

That said, 8½ is a true example of modernist cinema as Federico Fellini proceeds to communicate Guido’s story through a stream of consciousness narrative. In other words, as Marcello Mastroianni’s character struggle’s creatively, he immerses himself in dreams of childhood memories and fantasies throughout the film, thus blurring the lines between his reality and illusionary world. Consequently, the film works as a revelatory window opening to the psychological and existential state inhabiting the mind of an artist, in this case Guido.

Furthermore, even though the transitions between Guido’s reality and fantasies are inconspicuous due to their shared mise-en-scene, Fellini nevertheless, among other filmic techniques, makes his protagonist self-conscious of the non-diegetic soundtrack. Therefore, the audience is constantly reminded that what they are witnessing isn’t real life but rather an artificial and artistic rendering of it.

3. Sunset Boulevard

Released in 1950, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard has often been cited as the director’s best and most influential film. Produced approximately twenty years after the transition from the silent era to the talkies, Sunset Boulevard captures the essence of the state Hollywood was in at the time of its release, in that it is the story of a forgotten and deranged silent film star named Norma Desmond who hires a screenwriter in order to write herself back into the big pictures.

Hence, in order to add realism to the movie, Billy Wilder cast two established silent era stars such as Gloria Swanson playing Norma Desmond and Erich von Stroheim playing the former’s butler. Ergo mirroring the fading of both their fictional and real life careers. In other words, Sunset Boulevard studies the effect a cynical industry has on aging stars such as Norma Desmond who, due to the arrival of sound-sync pictures, lost her celebrity status therefore forcing her into seclusion and delusion.

That said, the film is perhaps the first attempt by a renowned Hollywood director to formally depict the more obscure side of stardom. Consequently, its influence can be observed in many subsequent movies that deal with the same thematic, most notably David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive.

4. Le Mépris

Considered as one of his most accessible and popular movie, Le Mépris by Jean-Luc Godard is also his first and most innovative work among his many films about filmmaking.

Released in 1963, it is Godard’s sixth yet first international feature length starring a star-stubbed cast including Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli as the main characters. That said, Le Mépris follows the life of a married couple as the husband, Paul, is hired by an arrogant American producer to help retouch the script of a film version of Homer’s The Odyssey directed by Fritz Lang.

Accordingly, what makes Le Mépris “one of the greatest films ever made about the actual process of filmmaking” as Martin Scorsese once said, is, for one, how Jean-Luc Godard doesn’t shy away when it comes to reminding the audience they are watching a movie.

In fact, the french director goes so far that within the very first shot of Le Mépris, the viewer starts off as a witness of a diegesis shot only to become a part of it as the camera operator pans and tilts the camera until it catches the viewer’s gaze. Thus, in doing so, the audience isn’t simply reminded of the artificiality of cinema but is also invited into the process.

Furthermore, Le Mépris ironically mirrors Jean-Luc Godard’s own friction between him and his producers as his artistic vision was stricken from him during production. Hence, not only is Le Mépris visually beautiful and highly poetic, it’s also primarily the young French New Wave director’s critical response to an industry that favours grossing revenues over creativity and artistic vision.

5. Inland Empire

Following a five year hiatus, David Lynch offers his most structurally complex film to date with the 2006 release of Inland Empire. Staying true, thematically, with the course of his previous release; Mulholland Drive, the small town director once again plunges into the world of an actress in Hollywood. Hence, Inland Empire follows the performance of a life-time by actress Nikki Grace, played by Laura Dern, as she progressively adopts her character’s, named Susan Blue, persona.

That said, what makes this film particularly stand-out is its capacity to blur the lines between the reality and artificiality of Laura Dern’s character as she continuously keeps the audience wondering whether she is acting as Susan Blue in the film-within-a-film titled On High in Blue Tomorrows or if she’s simply Nikki Grace.

In addition, as it is known that David Lynch builds his movies around certain images or specific ideas as opposed to figuring out the exact storyline first, Inland Empire’s fragmented narrative and temporality is evidently reflexive of his creative process.

Being both David Lynch’s most under-rated and longest feature film with a running time of three hours, Inland Empire is a rollercoaster of a movie that mustn’t be watched but rather experienced. It engulfs its viewers until the end only to release them puzzled yet satisfied.