16. Open Your Eyes (1997)

Though Eastern Europe would have to wait for political change until much later in time, Spain was able to throw off the chains of Fascism in the 1970s with the death of long time dictator Francisco Franco. This opened Spain up in many ways, not the least of these being Spain’s film industry, which became lively indeed.

One of the most promising talents to emerge in the post-Franco era was Alejandro Amenebar. Though he would not fully come into his own until the 21st century, his breakthrough came with a dreamlike film which had a dreamlike history of its own.

Open Your Eyes is a tale told by an imprisoned man (Eduardo Noriega) in a prosthetic mask. The story he relates involves the days when he was handsome and desirable and fell in love with one woman (Penelope Cruz) while being obsessively loved by another, deeply disturbed woman (Najwa Nimri).

The course of the tale involves disfigurement, suicide, murder, identities magically transforming, and cryogenics. Though it may be termed science fiction, this film was also in the surreal tradition of David Lynch (and bears a marked resemblance to Lynch’s film Lost Highway).

It shouldn’t be a big surprise that Hollywood decided to remake it. The surprise, though is that Cruz was recruited to reprise her role (which set her on a successful international career) and Amenebar was asked to help adapt his original for director-writer Cameron Crowe’s remake, 2001’s Vanilla Sky, featuring Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz. The film was not disgraceful or unworthy but it wasn’t a hit, either, and pointed up the “rightness” of the original film.

17. Beau Travail (1999)

One of the finest and most original cinematic voices in modern French cinema is Claire Denis. Both a university professor and a film maker, among several talents, Denis made a splash from the time of her 1988 debut, the semi-autobiographical Chocolat.

For many, however, her finest hour was Beau Travail, a loose modern updating of noted American author Herman Melville’s Billy Budd. The plot concerns a former French Foreign Legion officer Sentain(Denis Lavant), who is at the point of suicide and is looking back over his time in the North African desert.

The daily routine was hard and harsh and he had maintained strict discipline but a new recruit name Gilles (Gregorie Colin), a superior creature in appearance, intelligence, and ability, threw the group and the commander into a turbulent situation (and repressed feelings are definitely presented as a possibility). The disturbed Sentain tries to destroy Cilles only to have fate turn the plot back on him.

If one did not know that a woman directed this lean, muscular, precise and inventive film (the last scene is amazing), it would not be apparent since this is not what is traditionally considered a “woman’s film”. Actually, Denis has always been a professional whose works should be above such considerations and this work is a gem.

18. Delicatessen (1991)

One happy element inherent in the cinematic world is the fact that there always seems to be some quirky, original artists who manage to have their voices heard and vision observed in memorable films which could only belong to that artist. In the case of this entry, co-director (with Marc Caro)Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s work could be mistaken for no others.

A Jeunet film is like a Rube Goldberg drawing in that it contains many intricate parts functioning together in ways which will make the device work unto itself perfectly. The plots are frequently like dark fairy tales for adults, but told in a lightly cynical, surprisingly breezy style which perhaps only a French/Gallic sensibility could master.

The plot frankly contains a nod to US director Terry Gilliam’s 1985 dystopian epic Brazil (and that director was the film’s North American godfather, helping it to get a release in that part of the world). The apocalypse has come and gone and the world is in one seriously freaky state. In fact, the great commodity of the day is food and no one is too particular about the source.

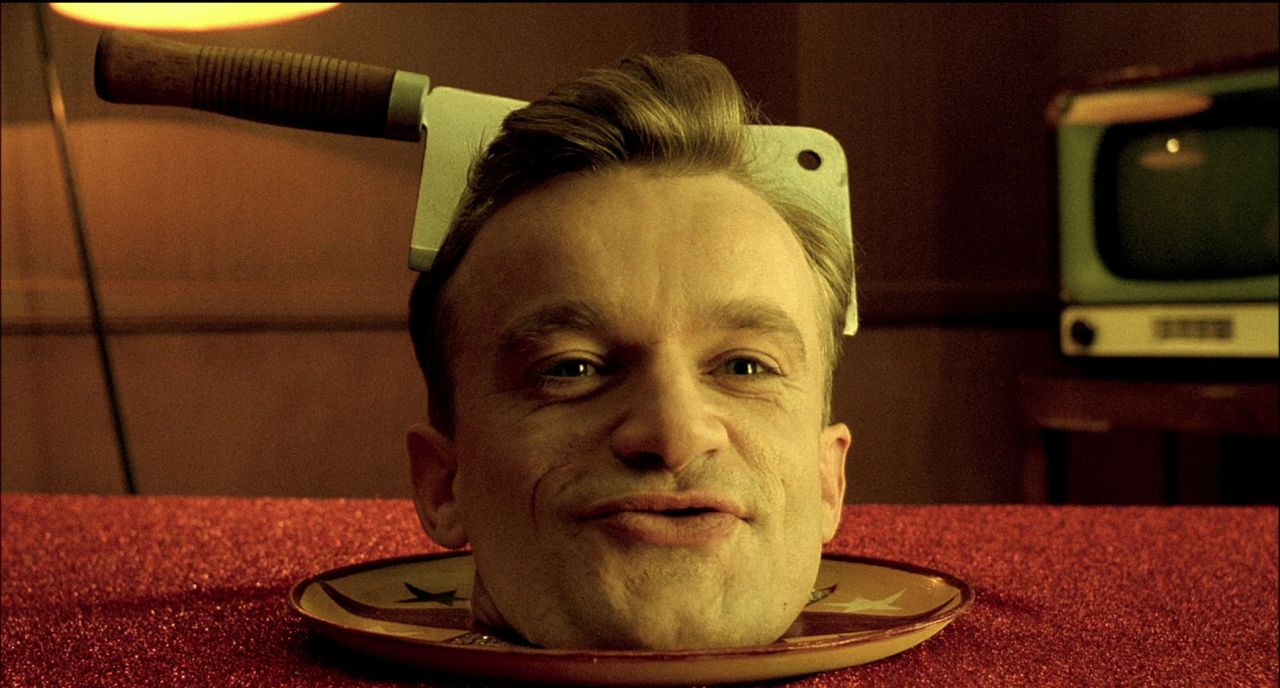

The main setting is a Paris apartment building where the tenants seem to keep “leaving”. This may well have to do with the presence of local butcher Caplet (JeanClaude Dreyfuss). Into this situation comes one time circus clown Louison (Dominique Pinon), who falls in with Caplet’s daughter Julie (Marie-Laure Dougnac) and, through her, is recruited to help her father.

Needless to say, their work involves turning the other tenants into food. Caplet plans to keep Louison working only for a while until it’s his turn to go but the young man and Julie have other ideas and involve a cult of subterranean vegetarian guerillas.

The film is a dark and wild, edgy and funny and treat for sci-fi lovers of a less serious bent and comedy lovers of a more serious one. It set the stage for the director’s better known triumphs.

19. The Long Day Closes (1992)

It’s a sad thing when something really good has to end (and most of the really good things seem to have to end sooner than later). For several years at the end of the Twentieth Century, the British government, though the BFI Government Board, subsidized emerging film artists with grants.

Many of these artists might never have gotten the chance to put anything on celluloid but for this program (and it’s loss at the start of the new century devastated the British film industry and stopped a number of films dead in their tracks).

The gold star graduate of this program was Liverpool born Terrance Davies. He had grown up in a very working class home in the 1950s and knew from an early age that he was destined to be “different”, i.e. gay. He was quite out of tune with his surroundings and loved some things (warm and accepting mother) and hated others (brutal and unyielding father).

Forced into a traditional type of job he was able to get into film making through the program and first attracted industry attention with a series of shorts which won many student awards. His feature breakthrough was 1988’s Distant Voices, Still Lives and its follow up The Long Day Closes. Together these films, plain and simply, tell the story of Davies’ early life.

These are not “story” films but, rather muted, distanced films which paint an impressionistic version of the time, place, people and feelings which the young Davies experienced. The pictorial style is very controlled and formal and the use of popular songs on the soundtrack, which frequently replace dialog, evokes the mood and feeling to spectacular effect.

It would be too much to expect these films to be hits with any but the critics or the discerning and they weren’t but few who have seen them will forget them. Davies never compromises and his output has been limited (though a new film is on its way in 2016!). However, like similar US film maker Terrence Malick, a new Davies film is worth the wait and search.

20. Irma Vep (1996)

European culture has always seemed to have more regard for the film medium and its history and creators than Hollywood has demonstrated over the years. Many a European film has paid tribute and homage to the history of the medium and one of the liveliest is this film, the product of one of the bright lights of French cinema in his era, Olivier Assayas.

Those who know French film history will recognized the name in the title as that of the chief villainess of the 1915-1916 serial Les Vampires, from creator Louis Feuillade. (This work, in fact, had only been saved thanks to a miracle of timing and those who cared enough to snatch it away from the trash truck which was coming to take it away.)

In this film a director well into middle age (veteran star Jean-Pierre Leaud, in what looks like a continuation of his role in the 70s classic Day For Night), has decided that he will create a new updated version of the serial. (Anyone seeing the original, admittedly important in the country’s cinematic history, would consider the idea far-fetched indeed.) He chooses Hong Kong actress Maggie Cheung (ostensibly playing herself) to portray the lead female character (originally played by an actress known as Musidora, who was a bit primitive as a femme fatale but effective at the time).

The actress is highly professional and manages to keep her dignity despite spending much of the shoot in a latex cat suit complete with a mask with a kinky vibe (not in the original). She also takes it upon herself to defend the rather convulsed director to a skeptical crew and press.

Though the film references the past it is also very much concerns the French film industry of the day and how a film is made (and though Assayas liked Day For Night, he found it unrealistic and designed this film for verisimilitude).

The action is wild and comedic but also respectful of the work. Encapsulating this is the fact that in real life Assayas and Cheung fell in love and got married…for two years, but still continued their more successful professional partnership. The director is still in his prime as a film maker, winning many awards and continuing to produce notable films.

21. Underground (1995)

Joy seems to last for such a short time in this world and it shouldn’t have been much of a surprise that the joy greeting the seemingly sudden fall of the Iron Curtain quickly turned to confusion and chaos in certain places. Nowhere was that fact more evident than in the country which had once been Yugoslavia.

Long held together by strongman dictator General Tito, the end of communism allowed many long suppressed ethnic divides to come to the fore and the results were traumatic indeed. In light of this, it seems appropriate that perhaps the finest film document concerning the place and its issues is also controversial to this day.

One of the regions finest film makers, Emir Kusturica (best known for 1985’s When Father Was Away on Business and 1988’s Time of the Gypsies) created a lengthy min-series for Serbian TV detailing the history of the land from the start of World War II through the 1980s as seen through the eyes of two roguish friends, one of whom becomes a resistance fighter (and doesn’t even realize when the war ends) by taking to the country’s huge underground canal system. It’s a tragedy and dark comedy and quite adept film craft.

The version the world outside of Serbia saw runs over two and half hours and the director bitterly objected to it being shown in any but the full multi-hour film format he originally created. Also, the content typically provoked deep division among the people of the region, depending on political affiliation. The western critics loved the film but, as ever, the Academy said no. Sadly, Kusturica has not had a big international film since but this one bids fair to remain a classic.

22. All About My Mother (1999)

For very many film fans around the world, the post-Franco Spanish film industry was justified and exhaulted by the existence of one film maker, if by nothing else. This would be Pedro Almodovar, a director-writer whose films have been increasingly mainstream delights since his debut in 1980. His early films were much like the works of US indie film legend John Waters, wildly aberrant and sexual (both men being openly gay) and delighting in shocking conventional society.

However, where Waters stayed deliberately a bit amateurishly rough and shallow, Almadovar gained in depth and understanding with the years without sacrificing his antic spirit (he also shows much more in the way of skilled technique than his counterpart).

Just as another US comedic film maker, Woody Allen, suddenly transitioned to much mature work after a number of youthfully callow films, Almadovar seemed to suddenly come of cinematic age with this film. Almadovar, like Waters, loves the melodramas of the classic Hollywood era, especially the deliberately overheated works of Douglas Sirk and this film, as is typical of his work, is done in an updated version of that style.

The plot revolves around a nurse (Cecilia Roth), who is also a single mother to a fine young son. Very sadly, the son is killed in an accident while running to catch the car of an actress he admires and from whom he wishes to attain an autograph. The grief stricken woman journeys to find the never present father, who was a transvestite.

During her trek she finds prostitutes, lesbians, Alzheimer’s patients, drug addicts, and a young nun who is pregnant and HIV positive…by the son’s father! It sounds outrageous and on some levels it is but during the course of the film the wild, cartoonish characters turn into real people with real suffering and the events descend into real tragedy…but also hope by the end, an Almadovar trait.

Highlighting this picture is the first Almadovar film appearance of Penelope Cruz as the young nun and who has since become a regular performer in the director’s films and has given some of her best performances under his direction. The film was one that finally pleased the Academy and won for Best Foreign Film, setting the scene for the film maker’s best years.

23. Burnt by the Sun (1996)

As the winds of political change swept Europe the former Soviet Union was certainly not exempt from those currents. Veteran film maker and actor Nikita Mikhalkov, who has long been a powerful force in state film circles, decided that particular moment in time was a proper point to examine the past. To that end he created Burnt by the Sun, a drama set during the horrific Stalin-sponsored purges of the 1930s (in this case one day in 1936).

Though not literally a true story, the film was inspired by historical events, namely the case of an army officer, a hero of the Russian Revolution, who was lead to ruin and death by old enemies. Sadly, the enemies had good cause for their actions for the officer was no innocent victim.

The director plays the officer, a man who used his political power to dispose of a romantic rival, only to have the man return many years later as the pawn of the officer’s rivals. The results lead to the destruction of the majority of the main characters.

The film’s postscript then reveals that the events were later declared a complete injustice…way too late to benefit the victims. It is inconceivable that a film this critical of even past Russian regimes could have been made in any era any less restrictive than the one which produced this film.

The film won the Academy Award and the Palm D’Or at Cannes and seemed to set the stage for Mikhalkov to soar to even greater heights. Instead, he used the success to stage a grand historical epic for domestic consumption which helped to consolidate his authority within the Soviet film industry. Oddly enough, he eventually created a sequel to this film, which seemed impossibility for those who saw the original and which remained a shining hour.